Rafal Pilat is a serial award-winning designer and co-founder of Mindsailors, based in Poznan but with an important presence in Asia and America, too. Mindsailors are proud to have a team of “designers with a lot of engineering experience and engineers with an artistic approach”.

BIG SEE is proud that Rafal accepted our invitation to serve on the BIG SEE Product Design jury. He was also a lecturer at BIG Design conference in 2022.

In a founding story about Mindsailors I read, that it was set up by disillusioned in-house designers. Almost two decades later, how do you now perceive the difference between independent and internal designers?

A story is a little more complicated, since we started on our independent path as the internal design studio for an Asian manufacturer. Soon, however, the big financial crisis of 2009 came about and we were told by our parent company that – if we wanted to stay – we should completely change our professional roles, as the company was switching from production into trading. And that if we were not prepared to do that, we would be free to set on our truly independent way … As at that point we had already adopted the name Mindsailors, and we were given permission to maintain contacts with former clients, this turned out to have been the beginning of the true independance for us.

Do you mostly work with clients who have no designers of their own?

We are very flexible in our aim to be most useful to our clients. It means we have both designers and constructors in the company, and we think of both fields as our core businesses. We are also employing a hard-ware engineer for quite some time, because we found that to be very efficient, too.

If clients with a design department of their own come to us, their designers are usually more oriented towards mechanical design and need assistance with design that looks more attractive than what their engineers could provide. We are ready to participate in projects from start to finish, but can step in at any point. Ideally we join at the planning stage, because in this case we can act as an advisory body and offer expertise on either electronics or industrial design. Our role often begins with the review of what has been done, and this is followed by an assessment of how we can assist in what clients are trying to achieve.

We also have clients who are not very specific about that, even in trying to express their idea. In this case it recommended that we join as early as possible since we can organize workshops with them to narrow their general idea into actual projects.

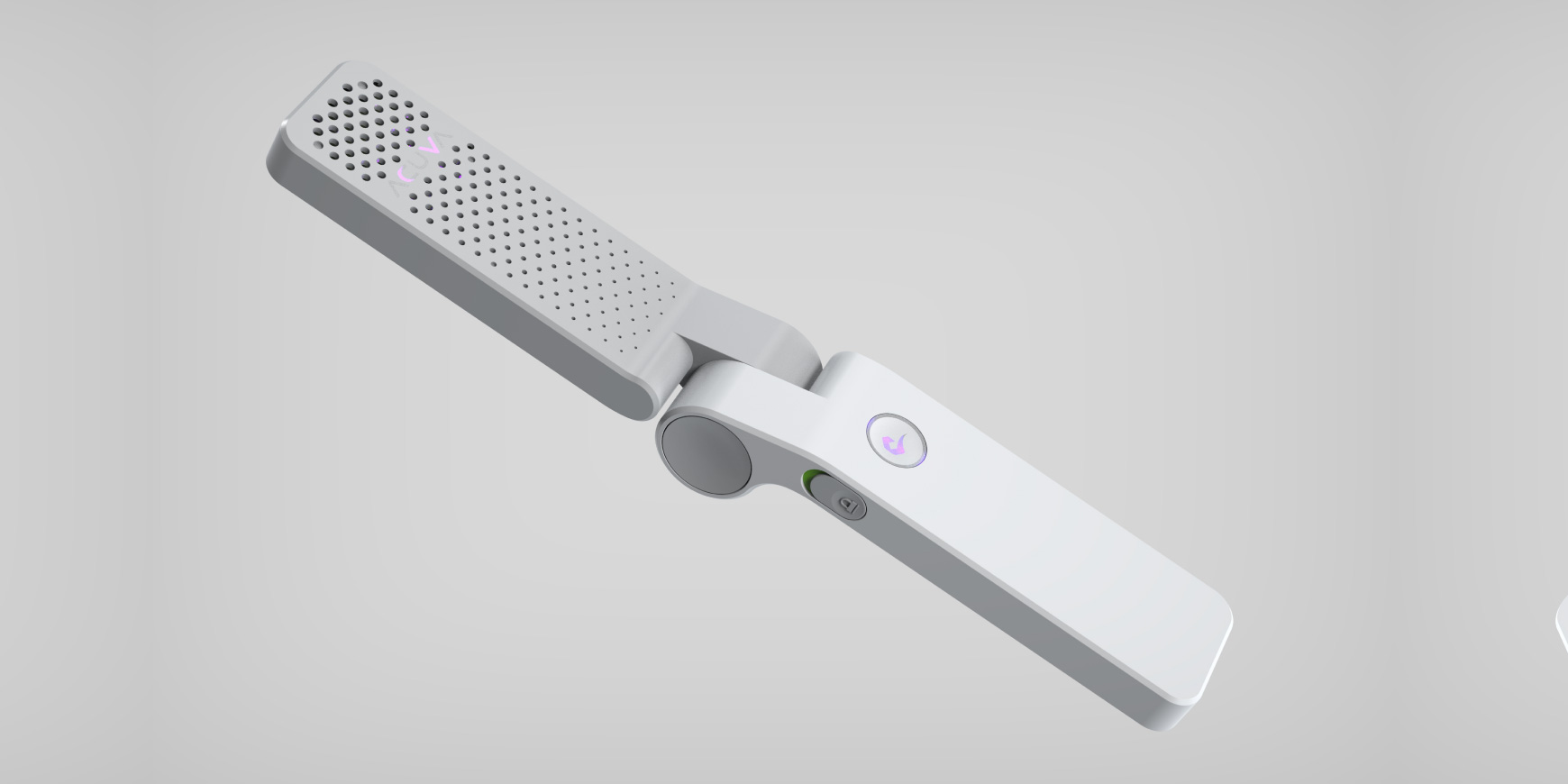

Acuva Solarix, designed by Mindsilors, is the most powerful disinfection device available on the market.

As early as in your breakthrough DICE project (2014) you’ve merged product design with engineering and even game design. Obviously in tech industry a decade is an eternity, but you have been early adopters in merging these three capabilities, and these mix only seems to have grown in prominence since.

Yes, we have started out as a company that does not provide only conceptual design services. We knew there were – and still are – agencies who focus on a very narrow aspect of design services, and who refuse to do anything else apart from conceptual design. This essentially means that they are cut off from the reality of projects which depends on mechanical or hard-ware design. We have clients who come to us with projects from conceptual designers – some even very well known among design experts – and often these projects are either completely unrealistic or they are extremely expensive to produce.

We always strive to be more than just another conceptual agency providing pretty pictures, and offer a broader scope of services including mechanical design and everything related to manufacturing. One-stop-shop may sound suspicious, but we really do have all competencies to execute a project from the very beginning to the very end and have resources to offer electronics, hard-ware and housing in terms of traditional design.

We often wonder if such broad expertise is actually still needed today, and if we really can assume such responsibility towards our clients? Responsibility is the key concept here: I’ll give you an example. We’ve had a client who was very satisfied with our mechanical design, but chose to continue the process with some manufacturer. The problem was that this manufacturer – who offered a fantastically low price – had no experience with housing for electronic products, previously they were only manufacturing buckets. Predictably the client came back to us saying, this looks terrible, what did you do? We told the client that we’d be happy to solve the problem, but that it was not us who caused it…

There is always the question about when our expertise should end, and at which point it is more or less economical for a client. Most clients are happy to be taken by the hand through the process, but they are all looking for the economics, and only a few have relevant experience with hard-ware projects. These are of course our most precious clients, because they know that building hard-ware is not easy, and they have very good understanding of problems that usually occur during projects. They know they need the help from experts, and they are aware that unpredictable issues almost always come up along the way. They push us more than anyone, but this is because of their understanding of our job, and we can give our best for such a client.

Long story short, each client is different, and majority of our time is not spent designing, but communicating and figuring out their needs.

Fortunately engineers speak the same language wherever they are from.

Although you mostly work in electronics, are there differences between industries in terms of expertise they expect from you?

Indeed, about 80 % of our projects is in electronics. But it is definitely the case that clients have different expectations, say in industrial equipment or electronics. We do quite many projects in medical equipment and this field is heavily regulated. It is therefore a very different challenge for us than if we are designing a toy or a piece of furniture – but there is always something or other that we need to take into account, be it standards or competition or some other requirement.

Just recently we’ve had a client come to us and ask us to do a research project. We were to do a feasibility study before the design project would actually begin. In a slightly humorous way it made me think that we just don’t get any “easy” projects anymore. We also have clients asking us for price estimates, and we need to tell them, guys, you are asking the wrong question: the question should be, if it is even real to make such a thing. We are starting ever earlier in the process and are working on more and more projects that are very exploratory in terms of new technologies which require from us a lot of time in the research stage. We have to narrow down many options to possible solutions which may be useful, because one never develops a project that is completely innovative from scratch. Usually it is about merging different soutions from different projects, and therefore selecting those that are the most reliable and easiest to execute. This includes either materials or their characteristics – just recently, for example, we were exploring whether a certain wind mill construction would deliver the needed amount of electric current – and sometimes we need to tell clients that we should all take a step back – or sometimes two or three.

Is making your (and your clients’) projects more sustainable becoming an important part of this research, too?

Yes, by all means. We are very enthusiastic about the Right to Repair initiative and we are actively promoting this idea to our clients that products should be easily repaired and also disassembled at the end of their life cycles. The reality, though, is that we can’t force it on our clients, because it is their decision to go one way or the other, but we still try to equip them with the necessary knowledge they need sometimes even in order to comply with expected future regulation about, say, disposal of certain materials.

On the other hand we did have clients who started out with high expectations about sustainability and biodegradable materials etc. – once we even did several injection tests with different plastics for hard-ware electronic housing, if we could achieve enough precision during mouldings. We tested for six months and with twelve different materials, yet in the end neither of the materials was suited for the device we were making. Each had some problems, either it requiered very specific processing or it didn’t offer sufficient cohesion with other materials. Our clients was very unhappy with this conclusion, but in the end there was no other option but to build the device with regular plastics, although we still used blends with some recycled material in them.

Quite often the realities of projects or clients’ expectations require us to step back, but whenever we can, we try to actively promote or at least convey our conviction about the principles we should adhere to as much as we can.

Award winning ultraportable spirometer AioCare that connects to your smartphone.

You have a representation in Hong Kong. Did you notice some differences in clients’ approach between countries and even continents, both in terms of sustainability or eventual other features?

The first thing that comes to mind are cultural differences. We work with many Asian partners, not customers, mostly manufacturers, and fortunately engineers speak the same language wherever they are from.

The biggest challenge is always to convey the idea and to make sure that the other side understands what we are trying to do. When this is the case, they also share the motivation to achieve the same goal. Getting to understand each other is of utmost importance regardless of national differences, and we have to work on that even with partners from Poland, not necessarily less than with people from China or India or the US. What matters is that we manage to get everybody “on the same page”.

Sometimes one feels that it is absolutely safe to assume that it is clear to the other person what we have in mind, but we have a rule in our company that assumption is the worst form of communication. With manufacturers we have a rule to “show AND tell”, and I cannot stress enough how crucial in success of every project is direct communication at every stage of the process. We find that it is essential to be able to explain even very technical problems in plain language, because not all people involved have sufficient technical expertise – but they need to understands the issues at stake.

So to come back to your initial question, geography matters far less when you manage communication well.

I have a similar question: some clients would ask for several ideas or solutions, so that they would be able to choose. However, design is, technically speaking, a problem-solving process during which suboptimal solutions are discarded. So, if the process is strict, several solutions are theoretically more or less impossible. How do you manage such situations?

Yes, the process works very much like you’ve outlined it. I remember a project, though, where we had a similar issue. The client wanted us to design a portable heart monitor with which they were not able to solve a critical feature: the device is placed on the patient’s chest and the electrode is glued to the skin. The client tried to solve the problem, but could not get away from the fact that the weight applied to the chest was around 2 kg. Our task was to reduce this weight, and we established that there were several ways how to achieve this, so we proposed to the client to test some prototypes. The client agreed, and at first we had as many as twelve ideas, all doable: first we eliminated those that were too complex or mechanically prone to preventable problems, and we ended up with three proposals that we and the client agreed that were promising. Later we eliminated one of those, too, because of problems with construction, and the remaining two were both working well as prototypes. Obviously the final selection was dictated by economics, and we chose the one that was easier to manufacture as it had less complex parts.

Long story short, when you have good communication, you can outline your process to the client openly, and they need to be aware that process takes time and with it, needless to say, money. And sometimes such openness brings us to the conclusion that the initial idea is impossible to produce with available means, be it technical or financial.

The heart monitor process was of course very close to an ideal scenario – unfortunately it is not always the case.

We mostly use local AI tools, because we need to take care online with content that is covered by non-disclosure agreements.

During past two years AI has been hyped in many industries. What has been your experience with it, and what are your expectations for the coming years?

We use these tools. They are excellent and they speed up certain things – even develop certain things. We were expecting clients to start coming with more specific ideas, developed by AI, but actually in these two years it has happened only once. A client showed us a AI-generated picture and said, this is more or less what we wanted – can you make it real? We were thrilled, because it saved us a lot of time to find out what the client truly wanted.

There were other challenges, though: even the very best AI images still leave so much to do that I cannot imagine AI would replace us anytime soon. Maybe in ten, fifteen years, but until then it is an excellent tool for generating initial ideas, some brainstorming ideas, and to make some visuals more realistic – especially when we include people with our proposals to make them seem more real with people wearing or using a device. Just recently we were even able to make some simple videos with it for an emergency medical device, and the clients were amazed, they said “it’s so real!” Sadly it was far from true, one might say we’ve made even too much of an impression. But it is obviously better than the other way around, right?

We definitely use many of these tools, and mostly local ones, because we need to take care online with content that is covered by non-disclosure agreements.

There are, however, several tools which would help us greatly, yet are not available yet, especially for finalizing technical documents which require a lot of time and precision, and probably could be done by an algorithm – it’s just a question of time, I hope. Another is CAD assistance, like when I want to attach two parts together and I try to generate some bonding between them – again it would be a lot of help, if an algorithm could propose several solutions etc.

I cannot emphasize enough that I absolutely don’t see these tools as any kind of competition, because building hard-ware requires lots of manual work, and it would take disproportionally long for a user to generate something, let alone manufacture it. Present day tools that let you print 3-D objects mostly turn out just sculptures and cannot be used for anything else, and above all not for commercially available products.

Technologically advanced TV decoder EVOBOX PVR.

Speaking of AI made me think of you at the time when you were making up your mind to become a designer. It was before the internet probably, in the early computer days, right?

Well, first of all my background is actually in teaching, I am formally a teacher of English. Of course I’ve enjoyed being creative even in childhood, and at twelve or thirteen I would use my Commodore 64 to generate images. I wanted to become a 2-D artist or any artist that works with a computer.

However, when I reached university age, Poland has not yet established a computer graphics school. There was just a Japanese animation school in Warsaw, and I didn’t want that. I went to study English and, interestingly enough, right there I met the guy who later founded our Asian partner company and gave me a job as a designer, but I barely touched 3-D back then.

Even later when we started Mindsailors at first I didn’t do much conceptual design, or if any, it was on flat surface, so I always needed other designers to transition to 3-D. It brings back the communication theme, as these designs were always sort of compromises for me: I would describe my thinking, and the designers would somehow visualize their idea of what I tried to tell them. I was very frustrated and I finally decided that I had to learn to use relevant software – frankly this was the only solution because I’m a perfectionist and I enjoy exploring different ideas. This is the only way to experience that magical moment when you look at something … and you just know that this is the right thing! Once you reach this stage, the process goes on smoothly, even if there are still many issues to work out, but once that magical threshold has been crossed, it is more or less on auto-pilot. Every designer has to find their own way to this magic, and for me it may have taken a bit longer, but like I said, we all have our own way.

Let me just add before we finish, how much I enjoyed my time in Ljubljana when I visited the BIG SEE conference a few years ago. I stayed for five days and had a wonderful time. I was also impressed by the regional focus – on top of the global reach – of the event, because the countries from the former Eastern block have great creative minds and impressive companies who have nothing to be ashamed of in comparison to the West.

Space Kotty is a smart litter box that tracks your cat’s health, uses UV technology for cleanliness, and monitors bathroom habits and weight.