Circularity for a Sustainable Future

By Zsuzsanna Molnár

“Reuse whatever you can: don’t clad it, don’t paint anything just to make it look nice,” say the two owner-managers of Bánáti + Hartvig Architects (BH), Béla Bánáti and Lajos Hartvig, whose firm is twenty-five years old this year. I talked to them about sustainability in their architecture and in their everyday lives.

It was in this spirit that they designed and reconstructed their new office building, where BH moved at the beginning of May. The architects believe that today it is vitally important to share their approach to sustainability and environmental awareness with a broader audience, and thus they set up the Green Commando working party in their office, and launched a podcast series, several episodes of which have already addressed this subject. However, they mainly strive to put their principles into practice in their design work.

The topic of our conversation is sustainability in architecture, so let’s begin with what sustainability means to you and what it means to your firm, Bánáti + Hartvig Architects.

Béla Bánáti: Our view on sustainability cannot be separated from our mindsets as individuals and our values. How we relate to the environment and environmental protection is largely determined by our upbringing. How we live our day-to-day lives is a question of personal attitude, as is whether we care about our children living happily and safely, and in turn raising their children in similar conditions. How we translate this into our professional lives is up to each individual. In our case, we must be fully aware that the construction industry is among the most polluting and energy-intensive industries. Whether we can add our own environmentally conscious convictions to this is down to our personal approach.

Lajos Hartvig: I would approach this topic in three ways. Like Béla, first, I would draw attention to the role of the individual. This is followed by the values that are held in our workplace, in our case in our firm of architects. I believe it is important for us, as managers, to be able to convey our views about sustainability to our colleagues and create a community where these are generally accepted. Indeed, it is even better if colleagues take them home and pass them on to their family and friends. Lastly, I wish to emphasise our views within our profession, within architecture, about the sustainability of the buildings we create. Here is just one specific example: I recently learnt that there are three tonnes of concrete for every person in the world. This quantity of concrete accounts for eight per cent of CO₂ emissions. That’s a vast amount. So, if we simply focus on one thing, on what concrete can be replaced with, we’ve already done a great deal. However, a building can do a lot for the environment from many other aspects as well. Yet it is important to highlight that building in an eco-friendly way needs to be learnt, and the principles applied to the buildings designed by us. This is what we endeavour to do in our work.

Where is all this apparent in your professional activities?

LH: Our goal is for the buildings designed by us to receive green certification in some form. Several of our office buildings have or will be given a LEED or BREEAM rating. Should this not be possible or the need to get such certification is not expressed by the client, our aim is still to reduce the ecological footprint of the building. So we try to convince the client that this is not an inconsequential consideration. With the office buildings I mentioned before, our job is easier as the client is also guided by business considerations, and these days it is difficult to let an office building that does not have green certification. Nevertheless, our experience is that working with a client who is personally committed to sustainability is different; working together is smoother. As far as the life of BH is concerned, right now we are moving into a new office building which we have designed for ourselves. We have created a building which communicates by its appearance that we are environmentally aware designers working with eco-conscious ideas.

BB: Let me add an example to the office buildings mentioned by Lajos, a building that stands out among cultural institutions: the New National Gallery building was also designed by us in collaboration with the architectural firm SANAA to meet a high green rating.

"I believe it is important for us, as managers, to be able to convey our views about sustainability to our colleagues and create a community where these are generally accepted."

I will ask you about the new BH office you’ve mentioned, but let’s stay with the previous topic for one more question, and bring in another significant event in the life of BH: your firm is twenty-five years old this year. Over the last quarter of a century, the concept of sustainability in architecture has evolved greatly and has become an integral part of the architectural discourse. How has thinking about sustainability changed at BH in those twenty-five years?

BB: Twenty-five years is a long time, and during that time our knowledge and awareness of and attitude to the subject have changed a lot. This is so not only personally but the ecological approach in general has also evolved a great deal. It began with our energy-saving efforts, for instance, by better insulating our buildings. This was followed by having the opportunity of planning buildings with increasingly advanced technical services, which were able to save energy but involved the installation of more and more mechanical and electronic devices. Gradually, the approach that we should try to simplify the technology evolved. In my view, the key here resides in the individual, in recognising that civilised people have to give up some of their accustomed comfort for the sake of sustainability. For example, do we really need to over-regulate the thermal system of buildings to cool the air inside to 22 °C when it is 30 °C outside in the summer? Overall, I can say that the attitude towards sustainable architecture has come a long way over the last twenty-five years, and at the same time our attitudes have changed a great deal as well.

LH: I will illustrate the processes that have occurred over the past twenty-five years with a story. In 1997, we designed a building for the German School of Budapest. Even then we tried to put certain environmentally conscious principles into practice following the guidelines at the time. So, we intended to install solar panels on the roofs, insulate the building to a better standard than was then required, and use grey water. At the time, we only managed to accomplish a little of this – but not because the client did not have a well-informed attitude. For example, the solar panel failed because the school is closed in the summer, when the solar panels produce the most energy. At that time, the electricity generated could not be fed back into the grid, hence this type of energy production would have been pointless. The use of grey water, however, was put into effect and rainwater flushes the toilets. We would have liked to install a pond in the grounds, likewise fed by grey water, but the idea foundered on the parents’ fear of the children falling in. But the story of the building of the German School of Budapest did not end in 1997. When the school needed an extension later, we designed a new wing, which was opened three years ago. In its design, we were able to incorporate a much greater degree of environmental awareness, such as the installation of solar panels on the roofs.

Owners, clients, tenants, architects, individual values and professional guidelines: many considerations about what influences your work have been touched on. Where does sustainability fit into these?

LH: Let me put this into perspective by expanding on an issue that Béla has already raised, that of the temperature inside buildings. As I have already said, nowadays clients commissioning office buildings tend to formulate a need for some kind of green certification, which has the added bonus of making such a building attractive for future tenants to work in. However, there is a limit, the question of comfort, which Béla also mentioned, that tenants find difficult to cross. For example, if we tell the client to allow the temperature in the building to be even 28 °C in summer and below 20 °C in winter, and get employees to wear a thick pullover, we immediately come up against an obstacle because it will be much harder for the client to find a tenant. So even when a need for sustainability is expressed, business interests cannot be ignored. In my view, broad education is needed in this area.

BB: I would add that social awareness is achieved in many steps. Maybe we have already taken the first, and we think that we are being nice guys by using a bike or an electric car, telling our environment that we are paying attention to this. At the same time, environmental awareness cannot be a matter of being nice, because it’s a question of survival. I’ll illustrate this with an example as well. The pandemic, which was caused by many factors including how we treat our environment, has blighted us for almost a year and a half now. One of its consequences, to mention just a simple thing, is that we cannot travel. In the very instant, however, that there was a breath of fresh air, decision makers were already pondering on how to stimulate tourism and recovery through state subsidies for the most polluting form of travel, aviation. The conclusion that can be drawn from this is that economic interests still outweigh all else, not to mention the degree to which waste management has been forced into the background by the hygiene required due to the virus situation, such as postponing the regulation on single-use plastics, to cite but one issue that also affects Hungary. In my opinion, a lot of progress still needs to be made in thinking at the level of the whole of society.

"I would add that social awareness is achieved in many steps. Maybe we have already taken the first, and we think that we are being nice guys by using a bike or an electric car, telling our environment that we are paying attention to this. At the same time, environmental awareness cannot be a matter of being nice, because it’s a question of survival."

The wide range of issues involved in sustainability that you have raised in the short time we have been talking shows the complexity of the subject. But let’s return to architecture. Let me ask you about the new BH office that was mentioned earlier. We know that sustainability, and within that circular architecture, played an important role in its design and construction. What were the principles behind the work?

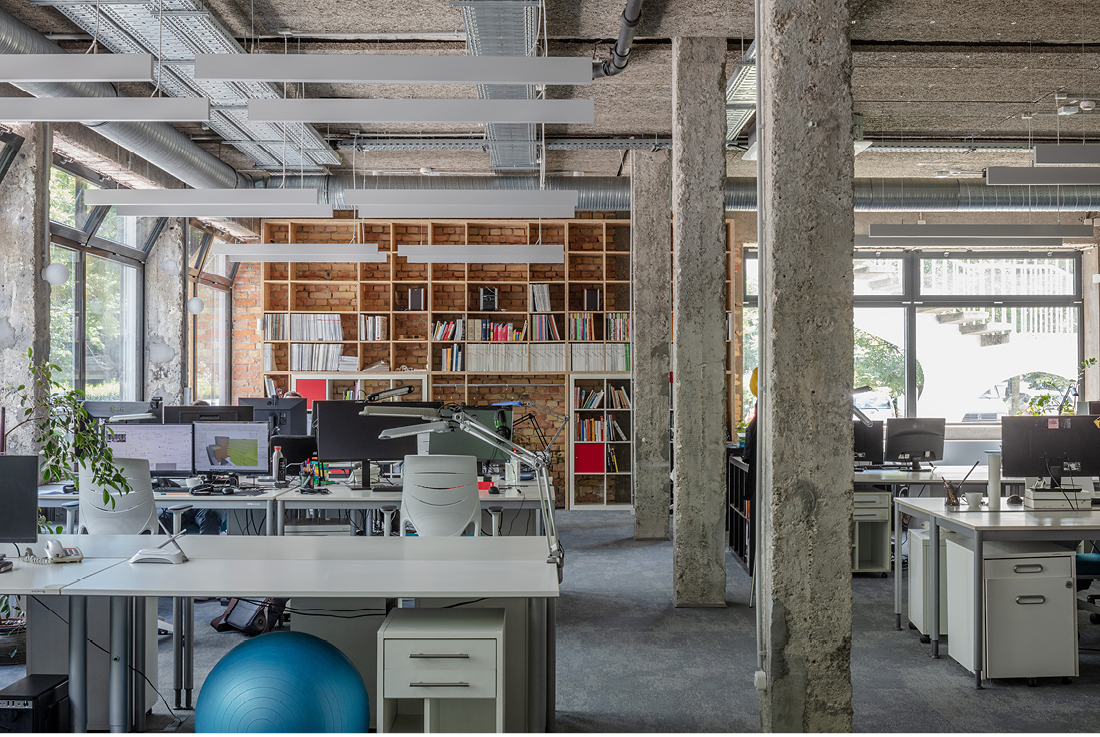

LH: Right from the start we rejected the idea of constructing a new building, and demolishing an existing building only to replace it with a new one was out of the question. We were looking for an existing building which could be used as an architects’ office in the future. So an essential factor was how a building that had previously been used for a different function could be transformed. Our office building was given a different spatial structure, circulatory system and purpose from those of the original, which allowed us to demonstrate that doing this is possible even when such a process seems complicated at first glance. An important move was opening three ceiling sections between the basement and the ground floor in order to make the building more suitable for functional needs. In this way, the basement receives more light and is included in the life of the ground floor. I think that the arrangement after the conversion will meet the needs of use and we will like working there. An important aspect was to demolish elements of the building only where absolutely necessary, and to reclaim any elements that were reusable after demolition rather than add new elements. For instance, the 1970s steel portal of the building was removed because it did not meet thermal insulation standards, but we did not throw it away. Instead, this was used to create the interior partition walls of our meeting rooms. We did a similar thing with the glass brick wall on the first floor, whose pieces live on as walls in the meeting rooms. We did not scrap the radiators which were still usable, but had them cleaned and reinstalled. On top of that, the idea of not cladding or painting anything just to make it look nice became our credo already in the design phase, hence, after demolition, the surfaces were left bare, creating an exciting aesthetic. We also tried to complete the building using the smallest possible amount of materials, and keeping the technical services and electrical elements of the building to the minimum. Another important aspect was to ensure that the building is accessible by public transport and bicycle so as to replace driving to work. These gestures will neither save the planet nor avert a climate disaster, yet I believe they are important steps if only because the building sends a message that is easily communicated to our colleagues, our clients and friends who visit us: we can show a model of our environmentally conscious way of thinking on a one to one scale.

So, in architecture, one thing that circularity means is finding a new function for reclaimed elements and reinstalling them in the building, isn’t it? What else do we mean by circular architecture?

LH: One of the most important principles of circularity is to use elements in construction that can be recycled after the building is demolished. Certifying building materials in the future according to the type of waste they will become – from hazardous to recyclable – is already being discussed. This is a trend in circular architecture that is still in its infancy, but we hope it will soon become an established practice. Naturally, it is harder to do this with a standing building, but keeping open the option of conversion is an important lesson. I think that we treated this building, and created the architectural and technical systems in a way that, in the future, any conversion which may possibly be needed can be carried out quickly and easily. Another important part of circularity is using sustainable materials such as wood. In furnishing our office, we have mainly used wood, and especially a type that is almost considered waste, as our shelves are made of OSB. Most of our furniture we brought with us from our previous office.

BB: Apart from the practical and environmental protection considerations, we also want to express a thought with this that runs much deeper: a building has its own history, but its place in the city also has a past. We haven’t yet mentioned that our new office is housed in a building with a long history in a well-frequented position on Fehérvári Road. It used to be the Alba Regia Restaurant, a catering and entertainment establishment, and then served numerous other functions, mainly as commercial facilities. We thought that this history could be reflected inside the building, in its interior design. For this reason, we did not cover the exposed surfaces, leaving the brick walls and structural concrete surfaces cast in the 1960s visible in their rough and ready state, because they tell us about the period and the building culture at that time. Through this we are able to express far more sensitively the mindset we have been discussing. Moreover, this also enables us to present a new, more sensitive aesthetic which makes this approach more acceptable to the people who need convincing that it is a forward-looking way of thinking.

"One of the most important principles of circularity is to use elements in construction that can be recycled after the building is demolished. Certifying building materials in the future according to the type of waste they will become – from hazardous to recyclable – is already being discussed."

Did putting these notions into practice involve sacrifices? If it did, how can these sacrifices be transformed into values?

LH: Many people had to be persuaded during both the design and construction that this would be good. Numerous opposing opinions were expressed. For example, we had to argue hard to talk the heating engineers into keeping the radiators. However, they insisted that we would have a lot of problems with the old radiators. They could be right but, if that happens, we’ll solve it. Another type of difficulty arose when we decided to dismantle the aforementioned glass brick wall in a way that it could be reused. As a demolition expert, Krisztián Petrovszki, put it, we didn’t smash the wall to smithereens. In other words, the glass bricks had to be removed carefully and cleaned. We, too, had to pay attention to this and consult with the contractor a few extra times, as well as having to dig deeper into our pocket. The term sensitisation is perhaps familiar from psychology, but it has been adopted by other disciplines, so there is no reason why we shouldn’t use it too. We tried to build this office in a way that it sensitises colleagues and visitors to the possibility of minimising the use of materials, reducing the amount of waste generated, and thinking about how waste can be recycled. If all this comes together as a big story, then everyone can take something home with them, and we can think together how we can transform the reflexes used in our design work until now into something different.

As the heads of an influential firm of architects, how do you see your role and responsibility in creating an increasingly green and sustainable built environment?

BB: Naturally, the most important thing is to put the approach we have been talking about into practice through our own work. Besides that, we would like to advance the idea of sustainability outside our office, in education, in professional life or even in public life outside the profession. We both teach at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics and, although education is moving a little slower in this field, I see optional subjects and efforts to promote and teach environmental awareness. We have an opportunity to spread this approach in degree committees and various planning councils, and heighten awareness among professionals of the importance of seeing this bigger picture.

LH: If you make me wear the hat of the head of an influential architectural firm, obviously, I would say that one of my most important goals is to train, raise the awareness of and sensitise my colleagues. If this way of seeing can spread throughout the office, then we are doing well. In my experience, many of our colleagues are interested in this subject, and are attending training courses and improving their expertise. That is one reason why we set up the Green Commando, a working party within the office focusing on eco-conscious design, and sustainable building materials and technologies. This is an independently acting team which organises in-house programmes, training and lectures, and intends to extend this outside the office in the future. Sustainability is an area of architecture that demands constant learning and must become a way of life. It is not enough to acquire the knowledge if I then jump in the car and drive every time I need to go somewhere. If it does not remain at a cognitive level but turns into action, then we are on the right road. And perhaps now we have come full circle, as we emphasised the responsibility of the individual at the beginning of the conversation, too.

The article was originally published in the journal, Építészfórum: https://epiteszforum.hu/korforgasban-a-fenntarthato-jovoert

The new workingplace building of BÁNÁTI + HARTVIG ARCHITECTURE OFFICE

Photos: Tamas Bujnovszky

Extension of Budapest German School

Photos: Tamas Bujnovszky

New National Gallery

Video and visual plans: VÁROSLIGET ZRT. – LIGET BUDAPEST