Mexico’s Urban Improvement Programme

For five decades, few architects had public or social commissions in Mexico, and it was not until the election of the left‑wing political party Morena in 2018 that selected architects were given the opportunity to design for the wider population. During his six‑year term in office, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) aims to bring about a better future for neglected populations by implementing roughly a thousand urban infrastructure projects in Mexico’s poorest and most dangerous neighbourhoods with the Urban Improvement Programme.

But there is a lack of time, money and experience among most of the people involved, as well as a lack of expertise and interest in maintenance after completion. For the project to have the best chance of long‑term survival, adoption by the population and the lowest possible maintenance requirements are crucial. In Mexico City I had an opportunity to talk to Román Meyer Falcón, a prominent figure in the field of urban and agrarian development, currently serving as the Secretary of Agrarian, Land, and Urban Development (SEDATU) in Mexico.

Meyer Falcón’s extensive background in public service and urban planning has positioned him as a key advocate for equitable and inclusive urban development in Mexico. His leadership has played a significant role in shaping policies and initiatives that promote affordable housing, land rights, and sustainable urban growth. In addition to his national role, he holds the position of President of the UN Habitat Assembly. In this capacity, he spearheads international intergovernmental efforts to address the challenges of global urbanisation, working toward the implementation of sustainable urban development goals on a worldwide scale.

How did the Urban Improvement Programme gets started?

When we started with this administration in 2018, we had already worked in advance with the transition team of Mr Andrés Manuel López Obrador, now the President. The idea was how we could establish a comprehensive programme that could address the major needs in urban contexts of high marginalisation. That is, those neighbourhoods lacking water, electricity, drainage, paving, basic services, and infrastructure. We set out to create a comprehensive programme to make those facilities and public spaces that do not exist in the neighbourhoods of greatest marginalisation, which, unfortunately, often – but not always – are the neighbourhoods with the highest crime insecurity.

In addition to this issue, the programme not only makes facilities and public spaces with an added value —architecture – but also, in the vicinity of the works, of a plaza, of a sports facility, within 500 to 600 meters, we provide direct housing support so that women, in particular, can make improvements: build a bathroom, add a second level to a home, install a water tank, make a door, apply waterproofing. They are not given the money directly. Also, within about the same radius, 500 to 700 meters from a facility, we deliver public deeds; that is, the documentation or possession title that proves that people own their homes. The fourth element of the programme is that in those same municipalities we update the urban development plans, which are the basis for the granting of construction permits. So, these are the four components of the programme: public facilities spaces, housing actions, regularisation of land tenure actions, public deeds, and something very important for us, the issue of planning. And so we do a lot of work with the documents that grant construction permits, that establish where we should and should not urbanise, and how we should do it as efficiently as possible, in terms of where housing goes, where commerce goes, where infrastructure goes, and so on.

And the component which I imagine this interview should focus on is one of the four pillars of the programme, the facilities. When we analysed this, at that time with Mr López Obrador – before he became President – we put on the table, so to speak, the possibility of addressing a specific type of infrastructure. Usually, when talking about public infrastructure or urban services, it’s the water, paving, and lighting that are thought of as the most important things. But we think that the most important urban infrastructure of all is something that brings together all the various elements: and that’s the idea of public space, which combines water, light, drainage, paving, vegetation and so on. And in marginalised neighbourhoods this idea of public space is often lacking, so that’s where we work in those neighbourhoods.

We do a lot of advance work with the communities. This means that eight months or maybe a year before a backhoe comes in to do the foundation we have participatory workshops with the community, with the local authorities, sometimes with the state government, to find out which of all the needs they have are the most important ones. Then perhaps they say “well, for us a high school is very important, because our children now need an hour and a half to go to the closest one.” Good, so now we have a priority, and then we can ask what else they need, because of course we have a limited budget. And then we work on a programme based on the main needs.

Every year a book with all cases of Mexico’s Urban Improvement Programme is published.

What were the criteria for the selection of the communities and locations?

Primarily, in 60% or 70% of the cases, the locations correspond to places where the Federal Government has some major infrastructure project. So, this means, for example: the Maya Train corridor, which is 1,600 km long; the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, which is 400 km long; the vicinity of the Felipe Ángeles International Airport; and the northern border with the United States, which was more of a fiscal incentive project. That’s where the programme supports the large federal infrastructure investments with its four components. So we attend or accompany these large developments. For example, in the case of the Maya Train for some of the neighbouring municipalities just having a train station does not mean there are any automatic, immediate urban benefits. So, to avoid having, let’s say, elements of great contrast, even if the train station influences or benefits a population one or two kilometres away, we still have very lagging neighbourhoods further away. We thus carry out complementary actions in those surrounding areas, far from the train station itself.

So in every location you need to do some preliminary research into what the community needs?

Yes, we arrive with a team of urban planners, architects, and sociologists, so that they can start working as quickly as possible with the communities and local authorities. And that’s where we make a basic master plan of the city. We say, “well, the marginalisation of this city, which is in the middle of the Maya Train path, is more prevalent in these neighbourhoods. These neighbourhoods are the ones with the greatest lack of basic services.” And among those basic services that are lacking we focus on public spaces. So we go from the general to start defining specific areas or neighbourhoods, and once we have those areas, with the densities, levels of marginalisation and needs, we go to the chosen neighbourhoods and conduct participatory workshops in coordination with the municipality.

And there we start to cross the different interests, because, for example, the municipality might say “I want this,” which is usually what the Mayor has in mind. But of course, it’s also important to listen to the Mayor, because otherwise he’ll say “you never asked me what to do, so why do I have to maintain and operate the space?” We thus have to cross-reference the needs of the community and the local authority, so that, as far as possible, both parties are satisfied and say “well, maybe it wasn’t what I wanted, but I agree that a high school should be built”, or “I agree that a fire station should be built”, or “I agree that a public market should be built.” With that, we start to define things, we find the best possible land which can be granted to us by the local or state authorities. We don’t buy the land, it must be given to us as a donation, because the infrastructure is then handed over to the municipalities, and belongs to them. So the high school, market or sports facility belongs to the municipality, not us, because the whole thing is a federal programme to support the local authorities.

How have you managed to carry out so many projects in such a short time? What’s the secret?

It’s an intensive job, there’s a lot of work, so there’s no secret, other than it being a team effort. But I also personally visit each of these facilities, each on average ten times. Before the backhoe comes in, I check the plan, and maybe I tell the people working on project “yes, move the building, move this here, place that there, it’s misoriented.” I do other visits during the preliminary works, during the foundation stage, during the formation of the structure, the configurations of facilities, and during the masonry, finishing, and completion stages.

There’s a very common phrase in Mexico: “a una orden dada, no supervisada, se la lleva la chingada”, which means that if an instruction is given but not properly overseen or followed up on, then it’s likely to be neglected, forgotten, or poorly executed. Which is something that this administration and government also understands. The President thus works as a construction supervisor. Every 15 days, for example, he goes to the Maya Train and checks the status of the project, because the only way to achieve these goals is for someone to physically supervise the work.

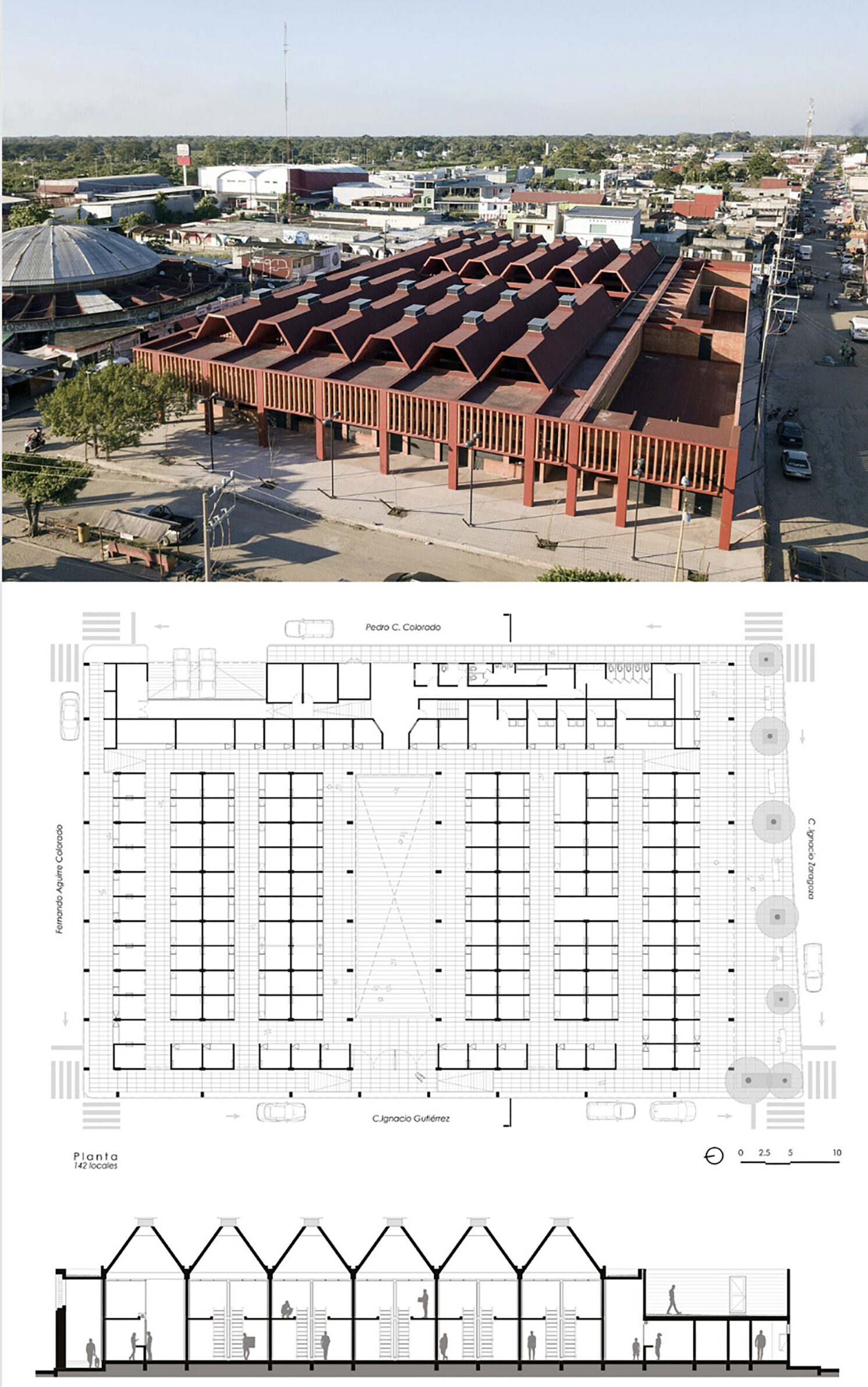

The new public market in Huimanguillo, Tabasco by 128 Arquitectura y diseño urbano replaces the old one, which suffered from a lack of maintenance and a high level of corrosion. Photo: © F8PHOTO, Alejandro Gutiérrez

You not only check the architectural work, you also work very strongly with the communities. How do you get the trust of people?

I believe in trust, but also determination. Because we cannot afford to be ambiguous. We have so little time to complete these projects – the whole programme, from planning to delivery of the work, has to ideally be done within a year or a year and a half – so you have to close the fieldwork as quickly as possible, and get everything agreed with the authorities and communities. Collaboration agreements are signed where it is stated “yes, we all agree that we are going to make the new public square here”, and everyone signs off on it. And, as much as possible, as the construction process goes on, any of the related social problems also need to be addressed.

Public works are a constant conflict. In fact, whenever and whatever you build, there’s conflict, whether it’s public or private. But when it’s public the conflict is greater, because it’s a matter of the common interest; because public funds belong to everyone, to all Mexicans. So many points of view and local interests come into play, which must be politically addressed as much as possible. Because otherwise, upon delivery, the reception and operation of the spaces can simple create more conflict. That’s why every two months we go back to each space and do supervision work: we check if there’s light, if the bathrooms are working, if they are open, if there are waterproofing problems, if the municipality is correctly carrying out the operations and maintenance.

As you can tell, it’s not only about the construction, but also about following up every two months with the local authorities to see if they are using and taking advantage of the work that’s been done. And if not, you call the mayor or the governor and say “listen, I have three abandoned projects in your state, what happened?” So there’s constant political pressure with regard to supervision.

But this work is worth it. For example, almost all the facilities that were made in the first years of the programme, in 2019 and 2020, are still active. Actually, I believe all of them are. Because a political effort was made to ensure their permanence. Now of course, when a work is delivered this does not mean that it will function perfectly the next day. You have to wait about two years for a sense of permanence to consolidate among the community, and for the local authorities to understand that it’s a place that needs continuous attention. So after delivering a facility we still need to work closely with it for a number of years.

The renovation of the Old Municipal Trail in San Cristobal de las Casas by the Laboratory for Urban Acupuncture creates new public spaces that allow the integration with the cultural elements that are part of the collective memory. Photo: © Jaime Navarro

And how did you do the selection of architects?

In the first year, we worked with Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) Architecture Faculty, for better or worse. Because UNAM, although a great national university, is also a very complicated bureaucratic apparatus, and when two bureaucratic apparatuses want to work together within a short time then it’s a disaster. But aside from that, it gave me the opportunity to get to know the work of many architects. It was, let’s say, a letter of introduction to many good and some not-so-good architects.

After that year of work, in which the university and the faculty carried out the executive projects, we were able to meet many architects and from there we began to define which ones were the best for what types of projects. Those architects or firms who were interested in reviewing the work on-site were chosen for more projects, because there were some who were happy to deliver the executive project but then never returned to the site.

An architect is forged in the field. Of course, it’s important that they enrol in a faculty and study, but real architecture is done in the field, and so the only way to learn is by going out to the actual territory. Therefore out preference is to work with those architects who we know return to the building sites, who supervise their own work without us having to pressure them. Those who return, review the project with the companies involved, with the directors, make their observations, and get involved. Who can talk to me when I make a visit, raise a hand and say what’s wrong and then, in front of the construction company, in the field, we can discuss things.

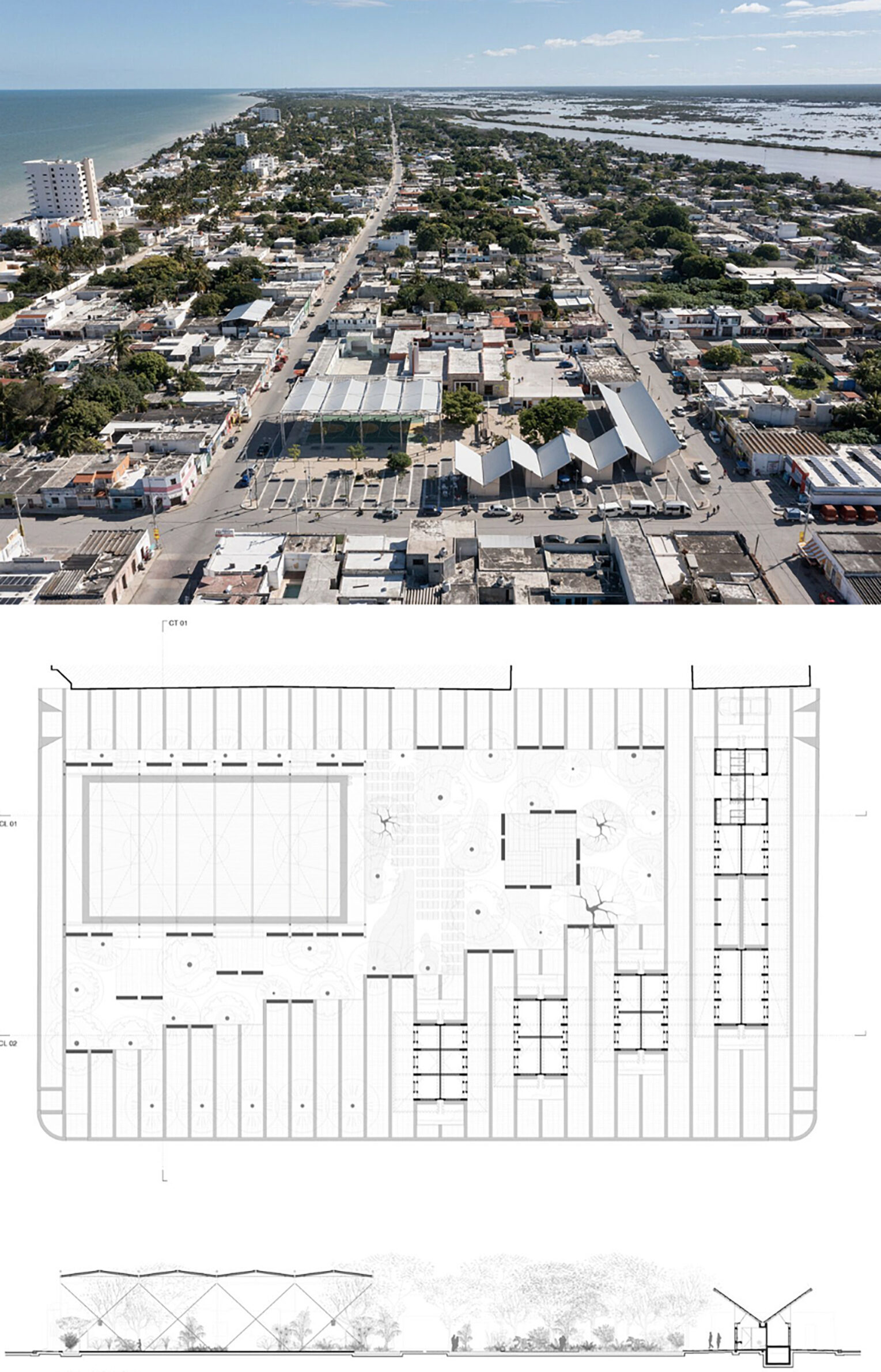

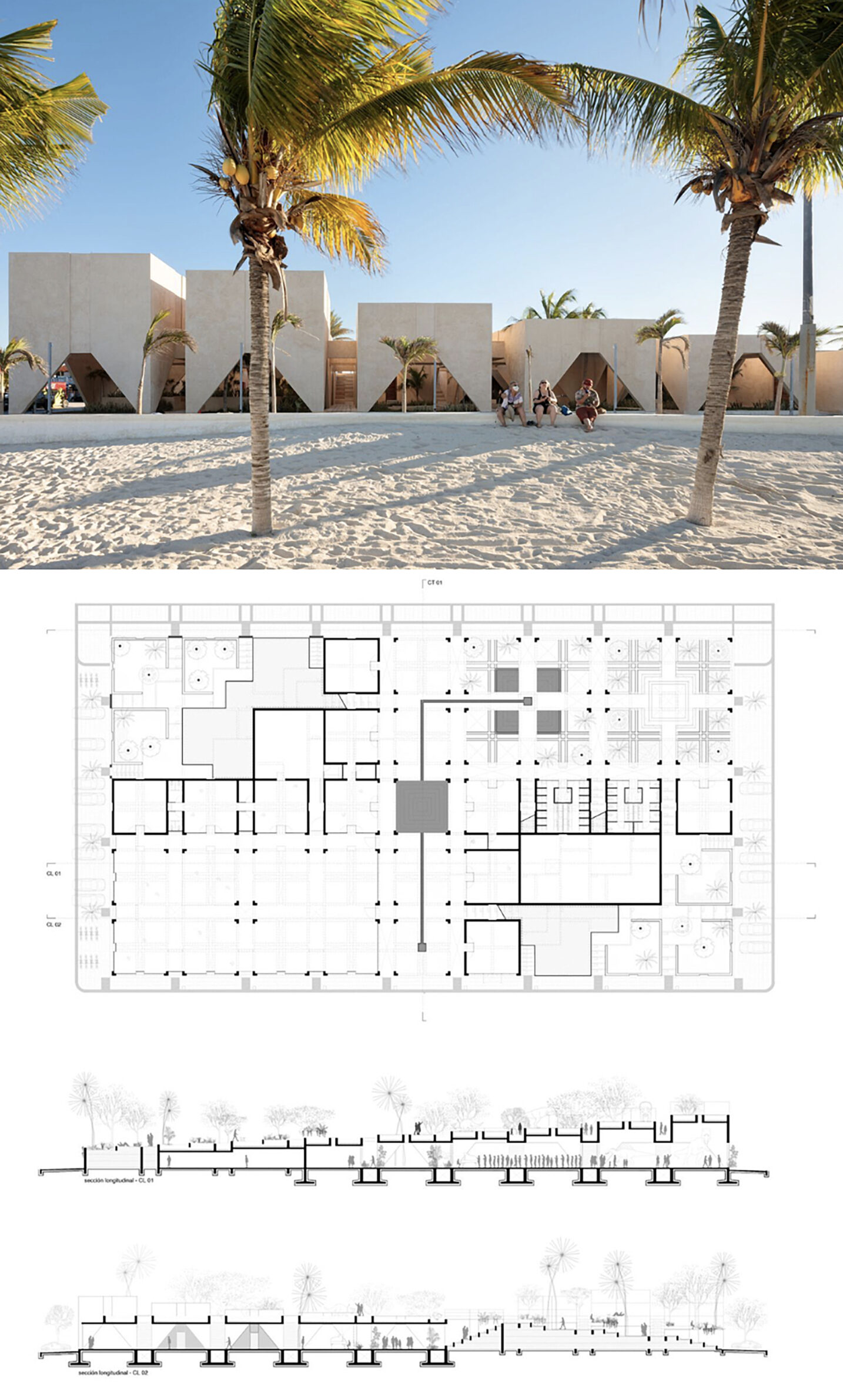

Chicxulub Market Square by Estudio MMX improves the square and the construction of the market. Photo: @ Dane Alonso

Bacalar Ecopark by Colectivo C733 reduces the requested programme to a minimum in order to be able to wander through the natural richness of the flora and fauna of the site, affecting these as little as possible. The lagoon is in the largest freshwater bacterial reef in the world. Photo: © Rafael Gamo

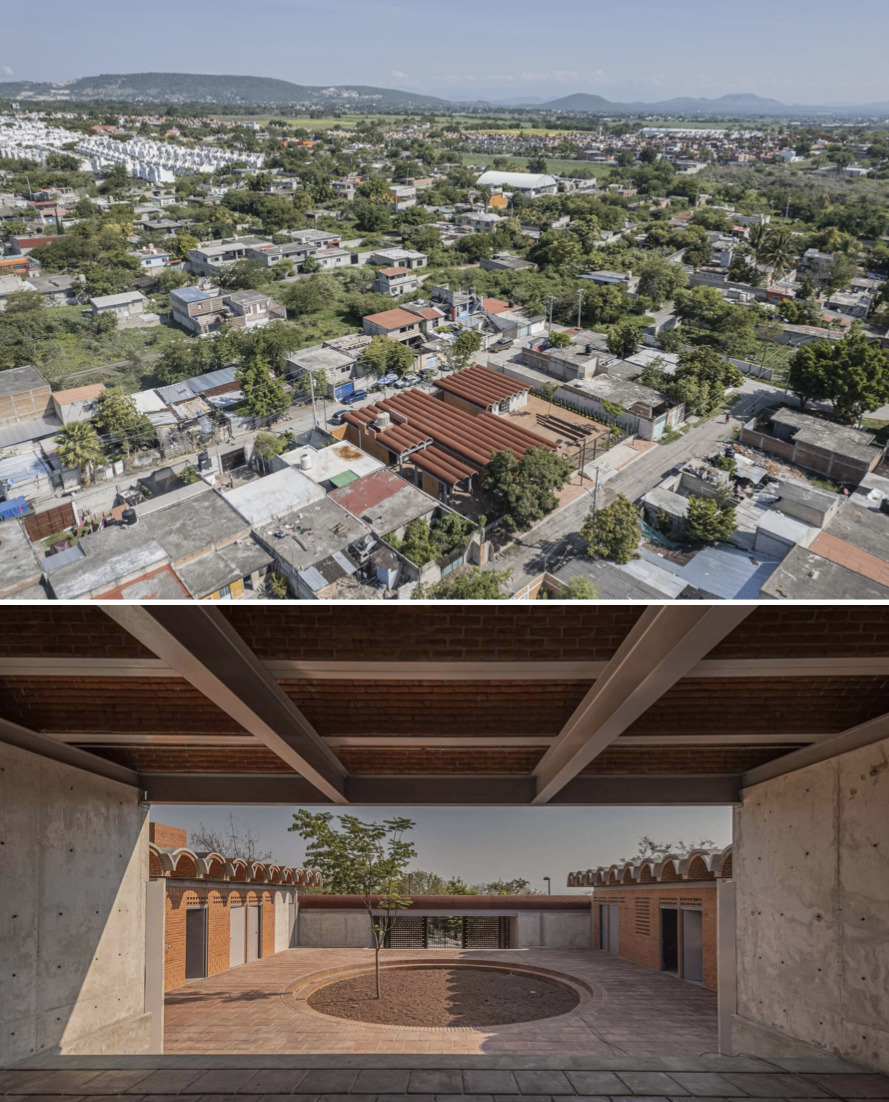

The House of Culture and the Kindergarten (CADI) in Tlatenchi by Taller CD represent two projects developed jointly, although in separate properties. Photo: © Andrés Cedillo

The renovation of the main plaza in Cosoleacaque, Veracruz by Colectivo MX, Gabriel Konzevik, Reyes Ríos and Larraín arquitectos improves the quality of social life based on an in-depth review of how and why people have used existing facilities. Photo: © Andrés Cedillo - Grupo Provimex

Museum of Geology by Estudio MMX in Progreso, Yucatan is a cultural element and an element of public space. Photo: © Dane Alonso

How many architects are included in the programme?

There must be more than a hundred now, and all of them are from Mexico.

Can you tell me about one of them?

Yes, for example, we have Loreta Castro Reguera from the firm Taller Capital. Just yesterday, we delivered a project of hers, the Bicentennial Park in the municipality of Ecatepec. It’s the most intensively used urban park in the country, located in one of the poorest and most densely populated municipalities. It also serves as a regulating basin, capturing and filtering water due to significant water shortages in the area. We also have Gabriela Carrillo, who has assisted us in many projects, as well as the company Estudio MMX, which is, let’s say, “special”, but good. Then I could mention Miguel Montor, who worked on the Mammoth Museum. They all teach somewhere, in addition to their practical work.

What’s next, will you continue to do this?

I believe so. You know, there’s a saying: “an old monkey doesn’t learn new tricks.” At our age, we’re already specialised in something. In our case, urban planning and architecture. It’s very unlikely that I’ll quit. So I have to stick with something I like. And it’s a vocation, something I enjoy despite the unfriendly bureaucracy and the fact that it is often very tiring.

For instance, I like the project I can see behind you: it’s the new Agrarian Archive, the second largest and most important archive in Latin America, located on Reforma Avenue, which itself is the most important avenue in Latin America.

This section over here is a Botanical Garden, with sections that range from jungle to desert, with different lighting conditions. It also has a public plaza with a small skatepark. Below is the entire archive, and we have the bureaucratic part as well. This is an example of the institutional projects that we undertake within the ministry without architects. These are the types of projects that we have been very enthusiastic about. This particular project is already about 65% complete. The structure is already up, and we are working on coverings and facilities. For example, there’s an Agrarianism Museum, which will be made up of pieces that blend in with the landscape and the botanical garden. We have pieces from the National Institute of Anthropology and History from the 16th and 17th centuries, which we will use as references for why agrarianism in Mexico is so important.

Text: Boštjan Bugarič

Photos: F8PHOTO, Alejandro Gutiérrez, Jaime Navarro, Dane Alonso, Rafael Gamo, Onnis Luque, Andrés Cedillo – Grupo Provimex, author’s archive