The zeitgeist has shifted towards recognizing nature as the essential basis of our living environment. And nature has also moved to the heart of architecture. In recent years, as it has repeatedly addressed the specific task of greenhouse design, DMAA has developed extensive technical and cultural knowhow.

With a population of 23 million, the megacity of Shanghai is the focal point of China’s urban and international development. The sparsely inhabited industrial suburb of Pudong has become home to one of Asia’s most spectacular high-rise skylines, at the heart of which the Expo Cultural Park is situated. But the Shanghai Region is also directly threatened by the consequences of unlimited growth and climate change. Given biting smogs, water shortages, and rising temperatures, the country’s leaders are looking for solutions that take the form of radical largescale steps – steps that should not only preserve natural habitats but also steer China’s technological and economic efforts in a sustainable direction.

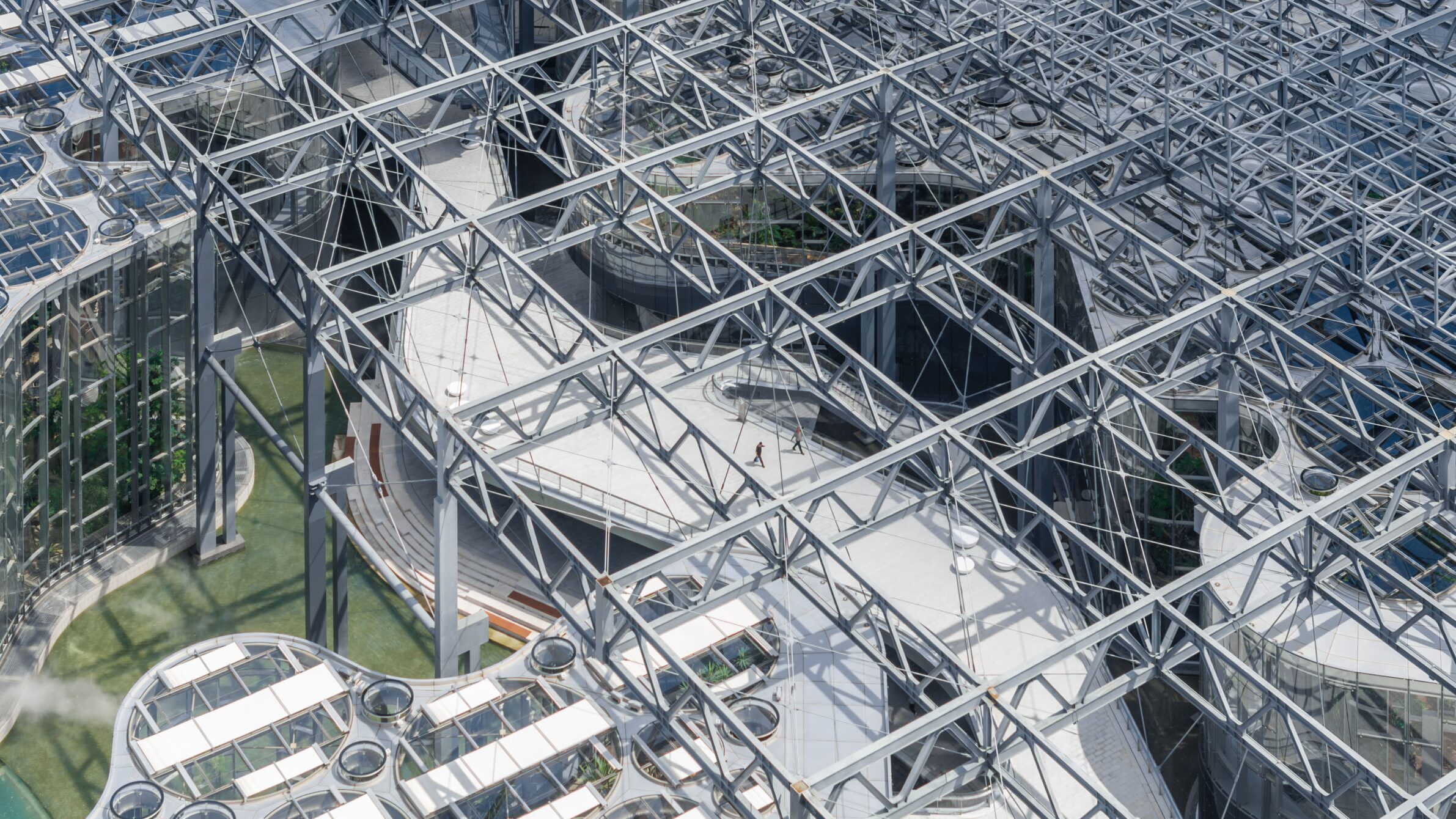

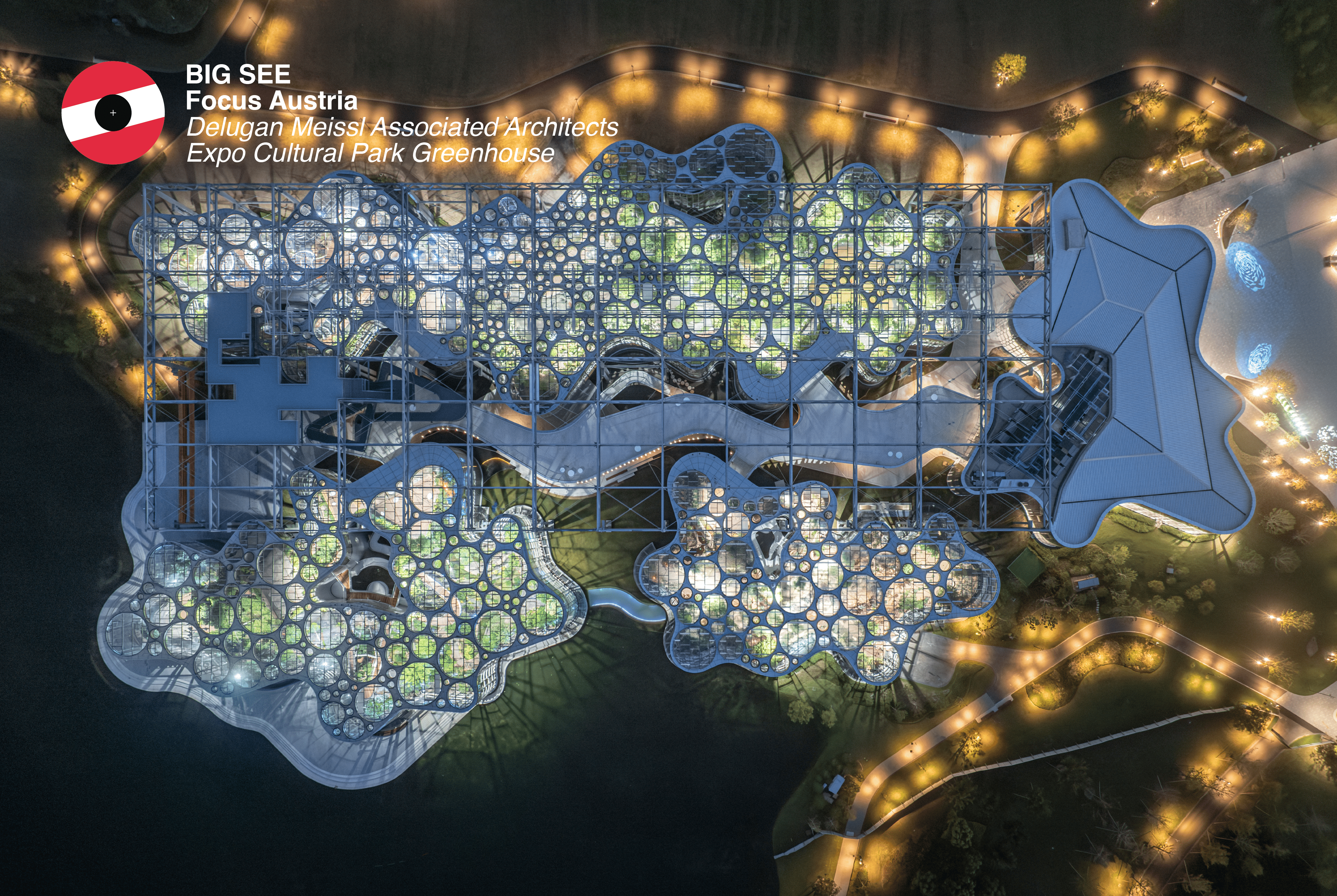

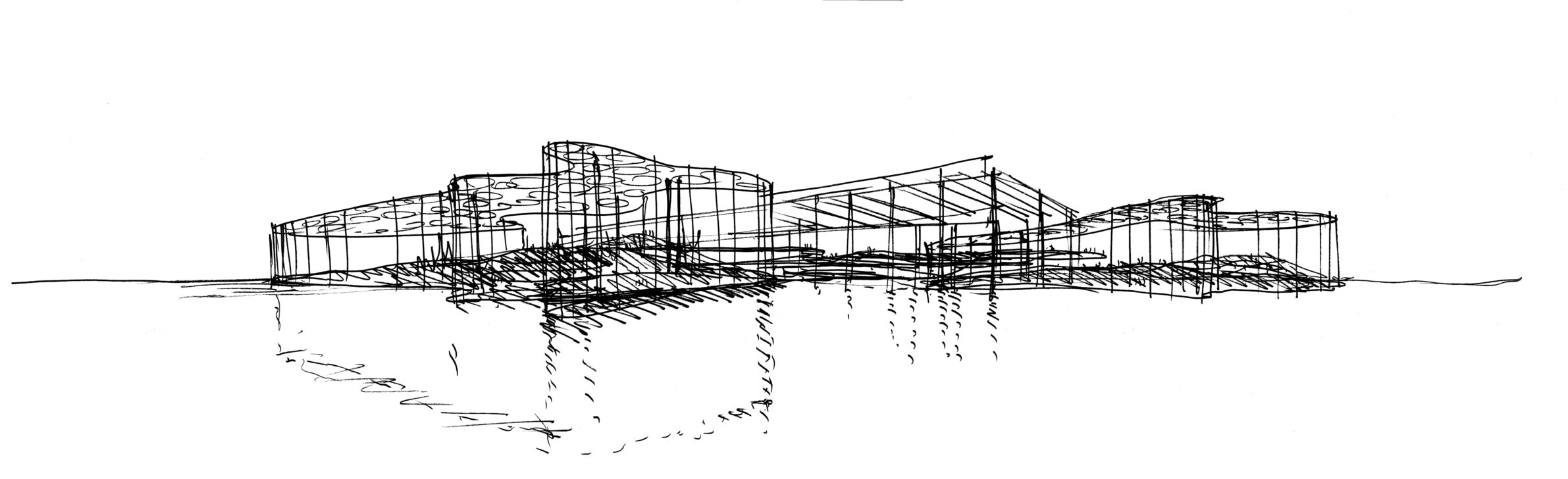

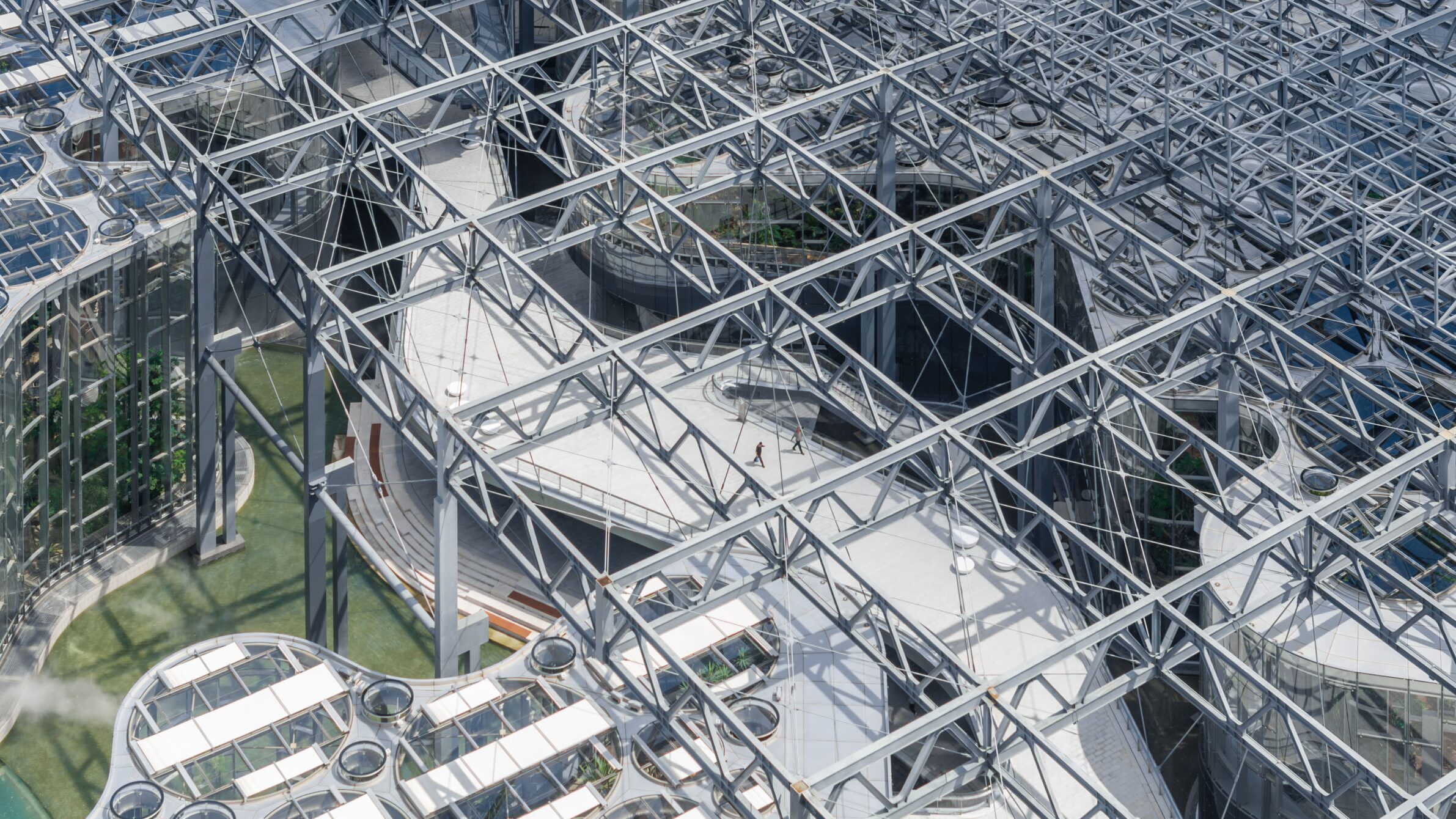

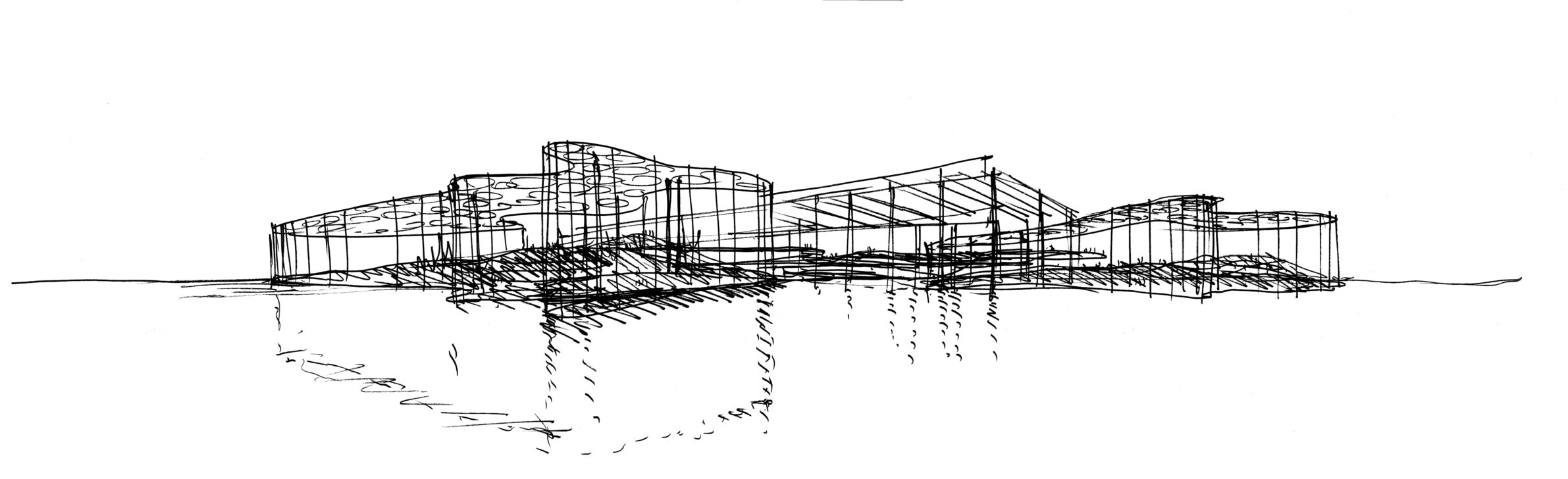

Before its transformation into the Expo Cultural Park, the inner-city recreational area was occupied by a coal-fired power plant and a steelworks. It was then remodeled as the location for Expo 2010. As part of the project for the new Greenhouse Garden, the steel structure of a former industrial hall was used as a geometrical superstructure that was then enhanced by organically shaped pavilions. The twin dualities of industry and nature and tradition and future mark the historical turning point at which Shanghai now finds itself. The municipal administration’s decision to re-function such a huge, centrally-located piece of land as a high-quality leisure area offers clear evidence of the overall trend towards the more intense planting of the core urban zones of Shanghai, one of the largest cities in the world with a subtropical climate.

As greenhouses generally consume large amounts of energy, one particular aim of this project was to create a zero-energy building. This was achieved by the use of single glazing – a choice based on simulative calculations that showed that double glazing would be less energy efficient due to the fact that the reduction in heat loss would be more than cancelled out by the impact of the artificial lighting required by the plants. Opening windows in the perforated roof can be adjusted to permit the natural ventilation and passive cooling that creates the optimal climate for the specific plants. A pool adjacent to the pavilions not only provides cooling but also supplies energy to the greenhouse from PV panels that are located just below its surface.

The first pavilion recreates the radical aridity of the desert, with a sandy and rocky landscape that embodies the home of plants that can withstand drought yet are threatened by extinction in every continent. In contrast, the second pavilion contains the tropical vegetation of the rainforest, while the vertical flower gardens of the final pavilion offer space for travelling exhibitions. The terrace above the pavilions offers an overview of the entire park and the buildings that form the edge of the surrounding urban fabric. Between the three pavilions and the entrance building, and below the listed steel structure, a largescale circulation space integrates the project into the surrounding nature.

The network of pathways within and between the greenhouses generates new qualities. By actively exploring this network, visitors pass through each spatial sequence, experiencing a targeted interaction with the built substance. Glazed parapets reveal these guests while gentle gradients speed up or slow down their progress. The variation in water levels between the desert and the tropical vegetation is taken from nature, while also offering a global political perspective due to the questions about the future availability of water that are being raised by climate change. In this way, the organically undulating form of the facade becomes a leitmotif for not only the internal organization but also the new adaptable relationship between humans and nature.

BIG SEE Talks with Roman Delugan

The inspiration for the “garden within a garden” concept came from a fascination with greenhouses as places of intense botanical diversity in a limited space.

Q: What inspired your interpretation of the idea of a “garden within a garden,” and how does it influence the way people experience the space?

A: The inspiration for the “garden within a garden” concept came from a fascination with greenhouses as places of intense botanical diversity in a limited space. They allow plants that would not otherwise thrive in the region to be cultivated and provide a home for endangered species. In the context of the Expo Cultural Park, which is itself a renaturation of a former industrial site, the greenhouse serves as the culmination of this transformation. It creates a dense, immersive landscape that takes visitors through different climate zones—from desert to rainforest to vertical flower gardens—providing a profound experience of nature in the heart of the city.

Q: What does this project say about the current relationship between architecture and nature in densely populated urban spaces?

A: The Expo Greenhouse reflects a paradigm shift in urban architecture: away from separation and toward the integration of nature into the built environment. In a megacity like Shanghai, which faces challenges such as air pollution, water scarcity, and rising temperatures, the project shows how architecture can actively contribute to ecological regeneration. By repurposing a former industrial hall and creating a vibrant green space, it demonstrates that sustainable urban development is not only possible but essential.

In a megacity like Shanghai, which faces challenges such as air pollution, water scarcity, and rising temperatures, the project shows how architecture can actively contribute to ecological regeneration.

Q: How did you approach the challenge of integrating sustainable solutions into a large-scale glass architecture?

A: The realization of a zero-energy greenhouse was a central objective. In collaboration with Transsolar under the direction of Thomas Auer, we developed an energy concept based on several pillars:

Single glazing: Contrary to common practice, we opted for single glazing because simulations showed that, in combination with natural light, this is more efficient for plant growth than insulated glazing with additional artificial lighting.

Natural ventilation: Adjustable openings in the roof enable passive cooling, supported by external, movable sunshades.

Underwater photovoltaics: Since the roof was unsuitable for PV systems, we integrated solar panels under the water surface of an adjacent pool, which also helps with cooling.

These measures demonstrate how innovative planning and technology can be used to create sustainable glass architecture that meets both ecological and aesthetic requirements.

Roman Delugan

About the Architect:

Roman Delugan is co-founder and partner of DMAA. Born in Meran, Italy, he studied architecture at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna and was a guest lecturer at at various universities in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. In 2015, he and Elke Delugan-Meissl were awarded the Grand Austrian State Prize.

Project

Expo Cultural Park Greenhouse Garden

Studio:

DMAA – Delugan Meissl Associated Architects

Lead Architect:

Roman Delugan

Project Manager:

Diogo Teixeira

Project Team:

Yue Chen, Jurgis Gecys, Thomas Peter-Hindelang, Toms Kampars, Prima Mathawabhan, Sebastian Michalski, Ernesto Mulch, Maximilian Tronnier, Toni Nachev, Marillies Wedl

Structural Engineering:

Bollinger + Grohmann

Energy Design:

Transsolar Energietechnik

Landscape Design:

Yiju Ding

Year of Completion:

2024

Location:

Shanghai, China

Contacts

Photography:

© CreatAR

Edited by:

Tanja Završki

Powered by

The zeitgeist has shifted towards recognizing nature as the essential basis of our living environment. And nature has also moved to the heart of architecture. In recent years, as it has repeatedly addressed the specific task of greenhouse design, DMAA has developed extensive technical and cultural knowhow.

With a population of 23 million, the megacity of Shanghai is the focal point of China’s urban and international development. The sparsely inhabited industrial suburb of Pudong has become home to one of Asia’s most spectacular high-rise skylines, at the heart of which the Expo Cultural Park is situated. But the Shanghai Region is also directly threatened by the consequences of unlimited growth and climate change. Given biting smogs, water shortages, and rising temperatures, the country’s leaders are looking for solutions that take the form of radical largescale steps – steps that should not only preserve natural habitats but also steer China’s technological and economic efforts in a sustainable direction.

Before its transformation into the Expo Cultural Park, the inner-city recreational area was occupied by a coal-fired power plant and a steelworks. It was then remodeled as the location for Expo 2010. As part of the project for the new Greenhouse Garden, the steel structure of a former industrial hall was used as a geometrical superstructure that was then enhanced by organically shaped pavilions. The twin dualities of industry and nature and tradition and future mark the historical turning point at which Shanghai now finds itself. The municipal administration’s decision to re-function such a huge, centrally-located piece of land as a high-quality leisure area offers clear evidence of the overall trend towards the more intense planting of the core urban zones of Shanghai, one of the largest cities in the world with a subtropical climate.

As greenhouses generally consume large amounts of energy, one particular aim of this project was to create a zero-energy building. This was achieved by the use of single glazing – a choice based on simulative calculations that showed that double glazing would be less energy efficient due to the fact that the reduction in heat loss would be more than cancelled out by the impact of the artificial lighting required by the plants. Opening windows in the perforated roof can be adjusted to permit the natural ventilation and passive cooling that creates the optimal climate for the specific plants. A pool adjacent to the pavilions not only provides cooling but also supplies energy to the greenhouse from PV panels that are located just below its surface.

The first pavilion recreates the radical aridity of the desert, with a sandy and rocky landscape that embodies the home of plants that can withstand drought yet are threatened by extinction in every continent. In contrast, the second pavilion contains the tropical vegetation of the rainforest, while the vertical flower gardens of the final pavilion offer space for travelling exhibitions. The terrace above the pavilions offers an overview of the entire park and the buildings that form the edge of the surrounding urban fabric. Between the three pavilions and the entrance building, and below the listed steel structure, a largescale circulation space integrates the project into the surrounding nature.

The network of pathways within and between the greenhouses generates new qualities. By actively exploring this network, visitors pass through each spatial sequence, experiencing a targeted interaction with the built substance. Glazed parapets reveal these guests while gentle gradients speed up or slow down their progress. The variation in water levels between the desert and the tropical vegetation is taken from nature, while also offering a global political perspective due to the questions about the future availability of water that are being raised by climate change. In this way, the organically undulating form of the facade becomes a leitmotif for not only the internal organization but also the new adaptable relationship between humans and nature.

BIG SEE Talks with Roman Delugan

The inspiration for the “garden within a garden” concept came from a fascination with greenhouses as places of intense botanical diversity in a limited space.

Q: What inspired your interpretation of the idea of a “garden within a garden,” and how does it influence the way people experience the space?

A: The inspiration for the “garden within a garden” concept came from a fascination with greenhouses as places of intense botanical diversity in a limited space. They allow plants that would not otherwise thrive in the region to be cultivated and provide a home for endangered species. In the context of the Expo Cultural Park, which is itself a renaturation of a former industrial site, the greenhouse serves as the culmination of this transformation. It creates a dense, immersive landscape that takes visitors through different climate zones—from desert to rainforest to vertical flower gardens—providing a profound experience of nature in the heart of the city.

Q: What does this project say about the current relationship between architecture and nature in densely populated urban spaces?

A: The Expo Greenhouse reflects a paradigm shift in urban architecture: away from separation and toward the integration of nature into the built environment. In a megacity like Shanghai, which faces challenges such as air pollution, water scarcity, and rising temperatures, the project shows how architecture can actively contribute to ecological regeneration. By repurposing a former industrial hall and creating a vibrant green space, it demonstrates that sustainable urban development is not only possible but essential.

In a megacity like Shanghai, which faces challenges such as air pollution, water scarcity, and rising temperatures, the project shows how architecture can actively contribute to ecological regeneration.

Q: How did you approach the challenge of integrating sustainable solutions into a large-scale glass architecture?

A: The realization of a zero-energy greenhouse was a central objective. In collaboration with Transsolar under the direction of Thomas Auer, we developed an energy concept based on several pillars:

Single glazing: Contrary to common practice, we opted for single glazing because simulations showed that, in combination with natural light, this is more efficient for plant growth than insulated glazing with additional artificial lighting.

Natural ventilation: Adjustable openings in the roof enable passive cooling, supported by external, movable sunshades.

Underwater photovoltaics: Since the roof was unsuitable for PV systems, we integrated solar panels under the water surface of an adjacent pool, which also helps with cooling.

These measures demonstrate how innovative planning and technology can be used to create sustainable glass architecture that meets both ecological and aesthetic requirements.