Architecture is also a cultural and educational activity

Lendarchitektur takes on a variety of tasks, starting with urban planning, designing residential buildings to planning small-scale projects and spatial interventions, and therefore advocates a differentiated approach from the pragmatism of practical constraints, to symbolism and local context. Their projects are a response to the existing environment or location and the needs of the users, and in addition to striving for highly professional work in all fields of architectural services, they fundamentally advocate and engage in public awareness of spatial culture. Their motto is: Architecture is not just a service, architecture is also a cultural and educational activity.

We spoke to the architect Markus Klaura, one of the co-founders of the Klagenfurt-based studio Lendarchitektur, who, together with the co-founder Sebastian Horvath, is also a member of the board of directors of Architektur Haus Kärnten, where they are often active as jurors in architectural competitions and lecturers on the topics of tourism development, the environment and society in the context of construction.

You have been active in the field of spatial creativity for more than 30 years, and have already completed many projects. What does being an architect mean to you, and how has your view on this changed over the decades?

I grew up with four siblings in a family of carpenters, and my father was an architect. Like my siblings, I couldn’t escape working with wood. So at the beginning of my training — as a 15-year-old — the focus was more on implementation and craftsmanship, but my desire to design soon grew. After graduating, many graduates thought they were already architects, and I thought so too. But really you start being an architect by taking on tasks and implementing them holistically. It’s in the nature of things that you need practice and experience. Otto Wagner — Jože Plečnik’s teacher in Vienna — said over 100 years ago: “You don’t become an architect until you’re 40.” Looking back, I can well understand this statement.

What’s the story behind the founding of the studio and the meaning of its name – Lendarchitektur?

In 2018, I was offered the opportunity to take on two larger projects under construction, which was a chance to form a strong and cross-generational team with younger colleagues. Lendarchitektur was founded in 2019 by Sebastian Horvath and myself, and Massimo Vuerich has also been a partner since 2024. The name Lendarchitektur comes from the location of our office on the Klagenfurt Lendkanal, an artificial waterway between Lake Wörth and medieval Klagenfurt, where I’ve been working since 2006. The name is intended to emphasise team spirit, because nobody does big projects alone.

In your realisations one can see a respect for the local context and a sense of listening to the needs of the community and the people you are building for. Which steps do you consider crucial in these regards when you create architecture?

It has always been my ambition to continue building in intact environments. Unfortunately, our landscape and towns bear the scars of a century of destruction. With the onset of industrialisation, a lack of or incorrect spatial planning led to disastrous circumstances, and wars have also left deep wounds. This is why urban planning and architecture have the task of intervening in a regulatory way to establish robust orders for the future. To plan effectively, one must understand the lessons of the past and anticipate future challenges. This knowledge is crucial when facilitating participation processes, ensuring that planning decisions are made in collaboration with users or laypersons in municipalities or companies.

Your projects often use sustainable materials, especially wood, which is an authentic and typical local material on both the Austrian and Slovenian sides of the Alps. What advantages do you think such natural materials have in architecture?

Wood is brilliant, but it’s use shouldn’t be treated as dogma. We utilise wood wherever it offers advantages. From a regional perspective, I view it as an economic, cultural, and ecological obligation to prioritise wood in construction in the Alps.

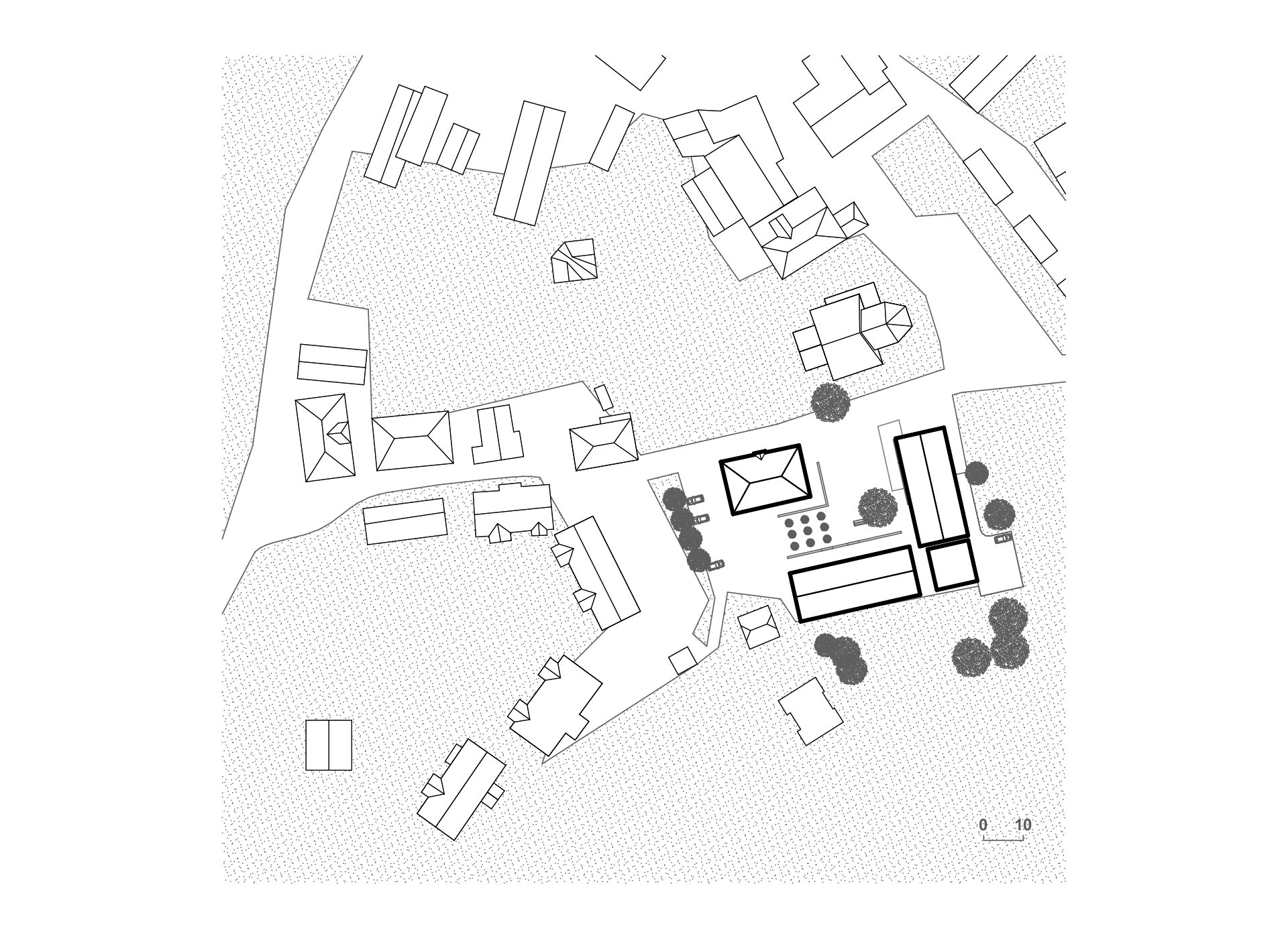

Neues im Dorfzentrum (The New in The Village Centre), Steiermark, Austria, 2022. Authors: Hannes Gfrerer, Sebastian Horvath, Markus Klaura, Massimo Vuerich; Lendarchitektur with Scheiberlammer Architekten. Photo: Christian Brandstätter

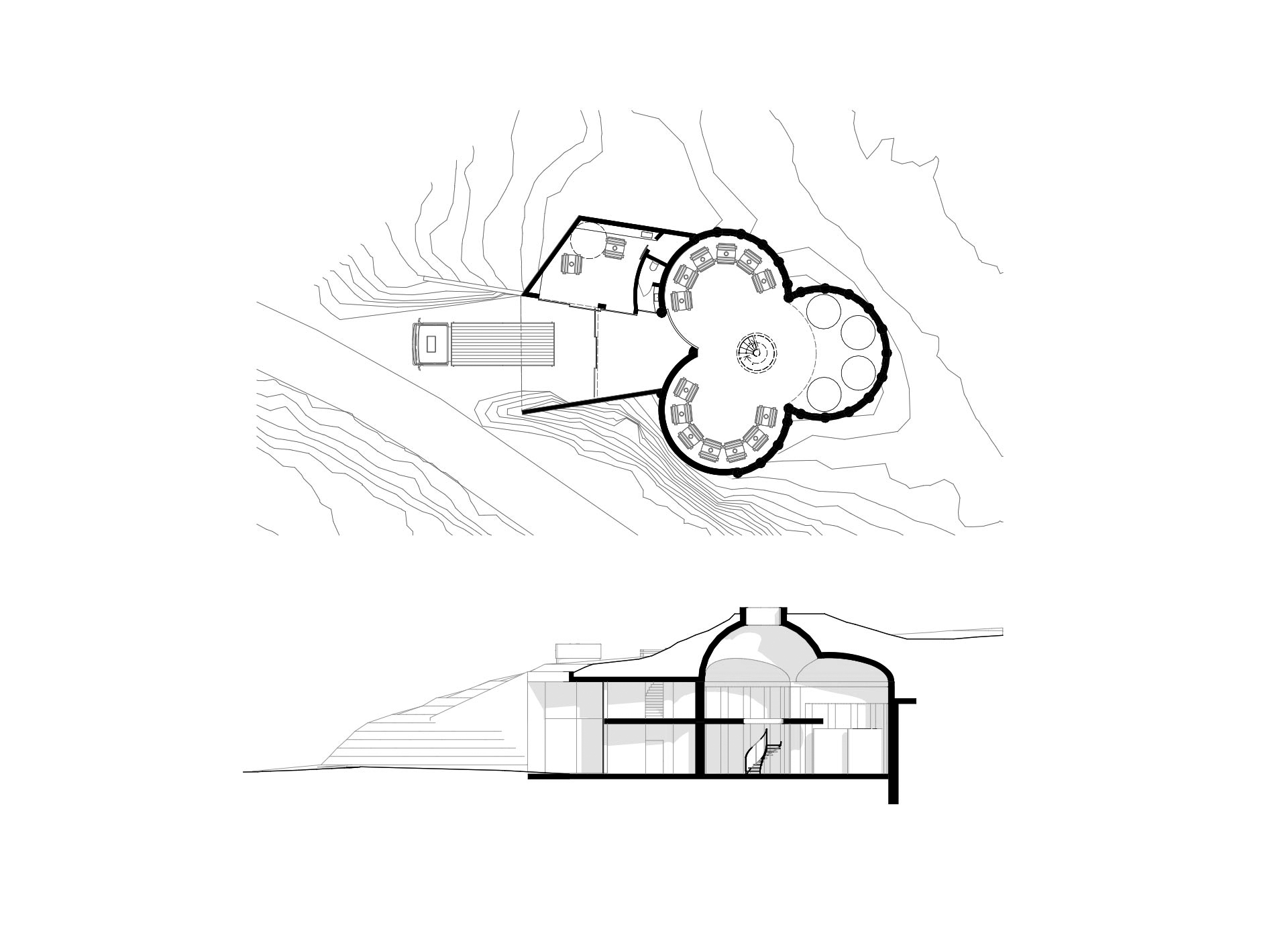

Wein im Berg (Wine in the Mountains), Goriška Brda, Slovenia, ongoing. Authors: Dominik Fasching, Markus Klaura, Massimo Vuerich, Lendarchitektur. Photo: Lendarchitektur

Arbeiten im Hof (Working in the Courtyard), Pritschitz, Carinthia, Austria, 2021. Authors: Magdalena Binder, Dominik Fasching, Sebastian Horvath, Markus Klaura, Massimo Vuerich; Lendarchitektur. Photo: Christian Brandstätter

In Slovenia most people still adhere to the conservative, established way of building and do not trust new, sustainable methods. But what is the public mindset in this area in Austria, or more specifically in Carinthia?

Here, too, industrialisation meant that building with wood was overshadowed by the use of mineral construction methods. The ecological movement of the 1960s and the associated return to natural building materials initiated a paradigm shift over 50 years ago. Beginning in Vorarlberg, Austria, a newfound confidence in timber construction emerged and spread beyond its borders, making timber construction socially acceptable once more. In this process, architecture and craftsmanship have developed new methods that will continue to evolve in the future.

What practical advice would you offer, based on your experience, to effectively shift this mentality in our country and demonstrate to people that living in buildings constructed with sustainable materials improves the quality of life for everyone in the long run?

Leading the way with examples of best practices and using contemporary marketing to spread these ideas through, so they are seen in parallel with concepts like “slow food” or “work-life balance”. Politicians should also take some responsibility in this regard.

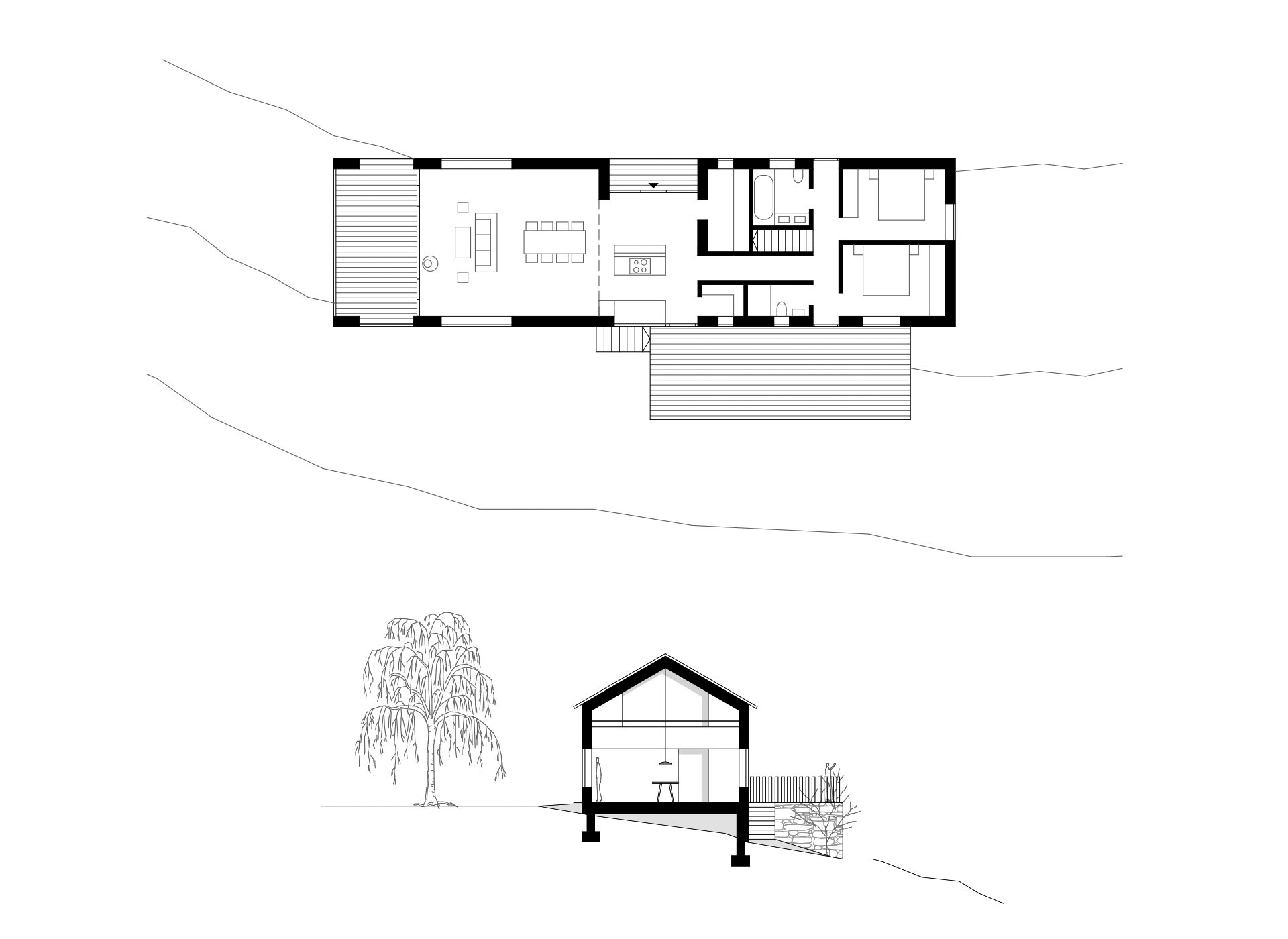

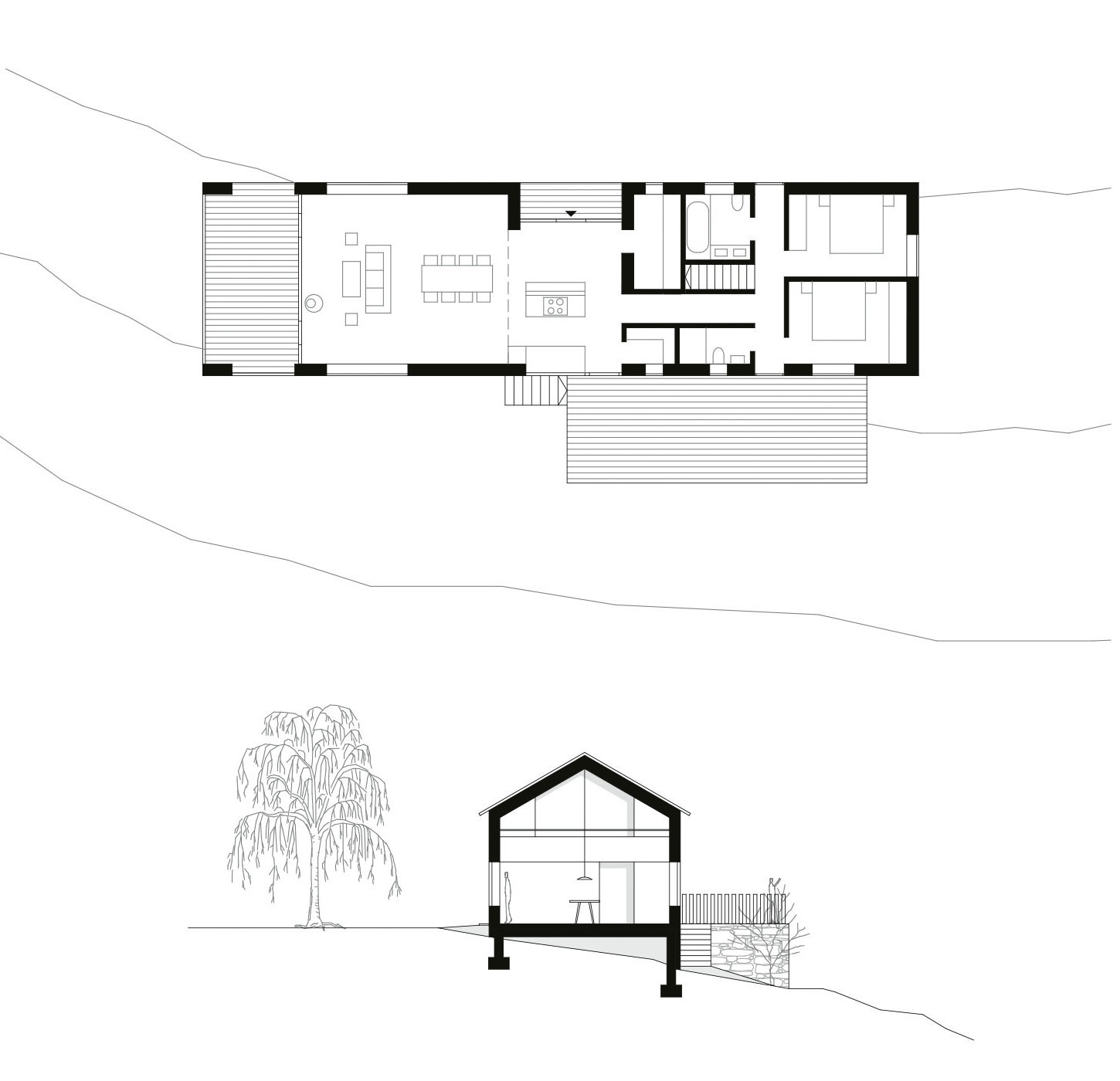

Haus auf der Höhe (House on the Top), Carinthia, Austria, 2017. Authors: Kathrin Brandstätter, Dominik Fasching, Markus Klaura; Lendarchitektur. Photo: Dominik Fasching

What do you think the vision for the future of sustainable architecture should be, considering both global environmental and societal levels?

Sustainable architecture begins with spatial planning and urban development. The goal should be to create flexible building structures capable of adapting to future challenges and changes. Prioritising the development of functional urban districts where living, working, leisure, and all the necessary infrastructure, such as transportation and energy, are integrated is essential.

What do you think the vision for the future of our architectural heritage should encompass?

Above all, repairability.

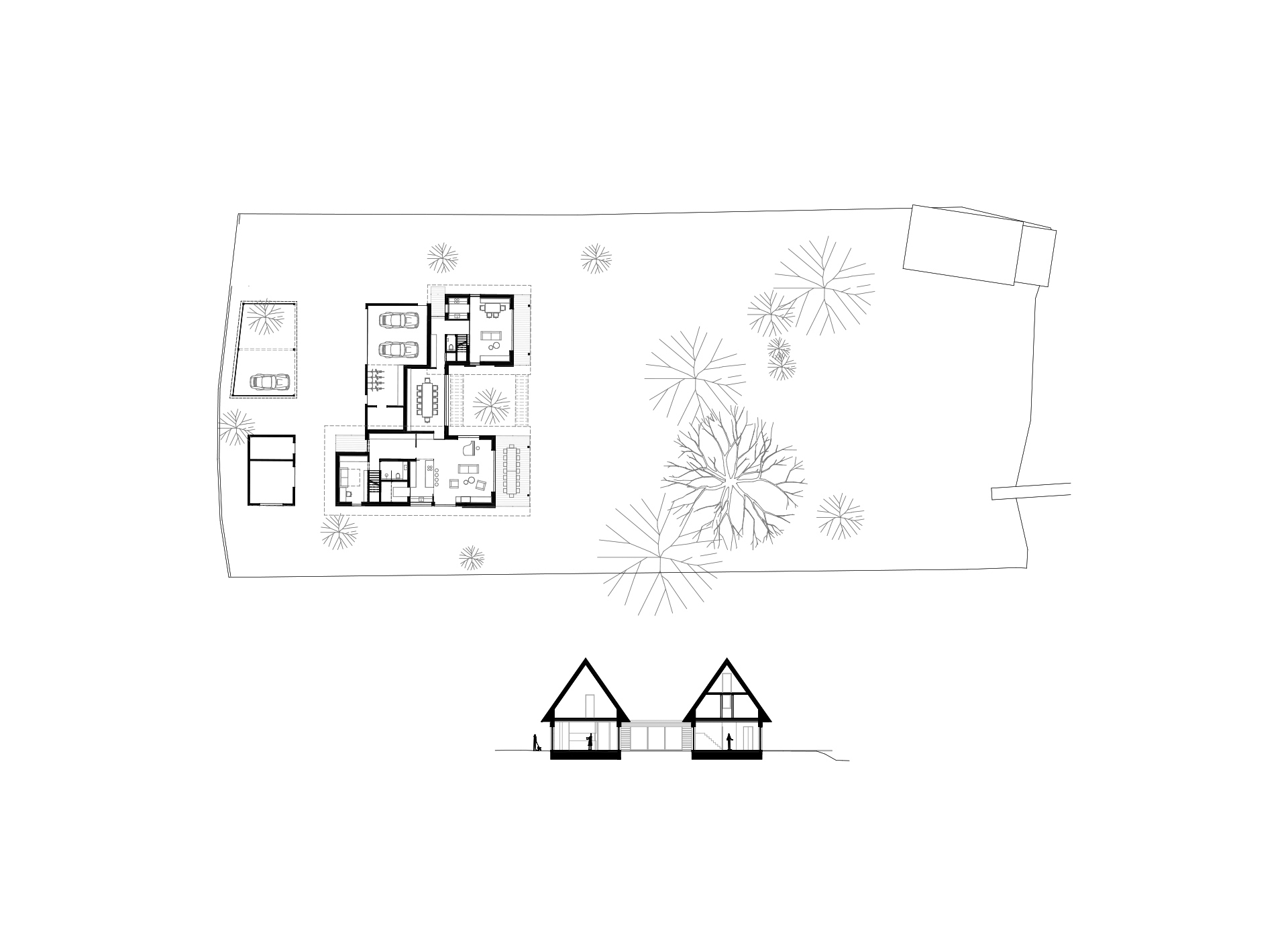

Häuser am Nordufer (Houses on the North Bank), 2023. Authors: Hannes Gfrerer, Sebastian Horvath, Markus Klaura, Massimo Vuerich; Lendarchitektur. Photo: Christian Brandstätter

Text: Timotej Jevšenak

Photographs: Christian Brandstätter, Lendarchitektur, Dominik Fasching