Jens Martin Skibsted (1970) is the founder and executive of several international award-winning design businesses, and also design magazine Ogojiii about innovation in Africa. His Biomega bicycles are included in collections of New York’s and San Francisco’s Museums of Modern Art. Among several international board memberships he also served on World Economic Forum’s councils on entrepreneurship and the future of cities and urbanisation. He was educated at ESEC film school in Paris, and holds a philosophy degree from the University of Copenhagen, as well as in business management from University of California, Berkeley. In 2019 several of his business ventures transformed into Manyone, of which he is co-owner and member of management board.

To start at the very top – Denmark and Slovenia are by far the most successful nations at the Tour de France for the past five years (two overall victories for Jonas Vingegaard and three for Tadej Pogačar, and each finished 2nd twice, too). Have you as a world famous bike designer ever tried your hand at designing a racing bike?

As a matter of fact I did, but with Biomega the whole vision was about urban biking which is a totally different proposition. The one design I did was for a mountain bike for the company called Pronghorn. I did the whole brand package for them, but I haven’t done any design for them lately. (Jens checks the web.) I see, now they make bespoke bikes, but also road, gravel, everything. Now that you mention it, I remember one thing about it that I really liked about the project: with Biomega we tend to hide anything technical, but with Pronghorn I went in the other direction. They discontinued this approach, but I kind of liked the way it looked hypertechnical.

These are the days just after the elections in America and at the same time Germany’s governing coalition is falling apart. It reinforces the message from past few years that Europe is falling behind Asia and America, and that it needs to sharpen its competitiveness. Your companies and your designs, however, are globally very successful. What’s your secret that obviously defies the geopolitical trend? It is Nordic heritage, is it design thinking, or some motivational touch you share with your teams? And above all, do you believe that Europe still has a chance?

I think it does. Obviously it is a very complex question, but let me just say that I have had Chinese co-owners at Biomega and it turned out a not very good collaboration. I also have experience from boards in several other companies, and, trying to stay polite, we are dealing with a very different business ethics here.

You see, in Europe we aim for collaboration, and this is not something businesses value either in China or America. For them it’s about crushing people. Just now I have heard a comment about American elections from a Democratic senator – and we Europeans tend to have more in common with Democrats than Republicans because of some shared social-democratic ideas – this senator said that democracy is “all about winning”. But it’s not! It’s about making people’s lives better and making them happier by letting as many as possible take part in decision making for themselves.

Europe may have grown a bit too holistic and we’ve lost sight of the ferociousness that is required in today’s business, but! – and it’s an important but – in industrial design we absolutely have the competitive edge. I’ll give you an example: I’ve lived and worked for some time in Berkeley, California, and a lot of American design is done around the Bay Area. I knew most of the important designers there, and almost all, a huge percentage of them were Europeans. This is great because it shows how strong we are, but on the other hand it can also be a weakness, because like the Americans, the Chinese also simply buy the design – while we cannot buy some cutting-edge technologies which they refuse to sell because of possible military use.

“In Europe we aim for collaboration, and this is not something businesses value either in China or America. For them it’s about crushing people.”

This happened to me with the first Biomega model: I was going to use the technology called super plastic forming and I could have bought it from the UK or Switzerland, but then it turned out it was also available in Taiwan which was great because a lot of top end bike components are also manufactured in Taiwan. But in the end we were told they couldn’t work with us because of military secrets involved – it was not the case at all, but it gives you the idea how it works. And mind you, this was more than a decade ago when there were no tarrifs and trade wars etc.

I have to say I actually believe in protectionism if it serves a purpose, not just some personal political agenda. I am all in favour of it when it protects our markets from products that do not share our levels of care for intellectual property and CO2 emissions. I really see no reason why we shouldn’t tax CO2 – Americans use fracking and its environmental costs are well known, so they need to be punished for using it. The same goes for Chinese use of coal, and I really think we should tax them like hell, make something good for the planet and level the playing field for us.

Sounds like a plan for the incoming European Commission. By the way, is the very highly regarded Danish commissioner Margrethe Vestager staying on?

No, unfortunately not. The national political landscape has changed and the new guys want their people in Brussels, too. A pity, because Vestager is really smart.

South-Eastern Europe, the focus of BIG SEE activities, is to a large degree part of the EU just like Denmark. What are your experiences with the region? Maybe you have some colleagues from the region or clients or projects?

Of course, I’ve been to Slovenia a few times and to Belgrade design festival, even to the seaside in Croatia. The most important, though, is the fact that my step-father is from Friuli, Italy’s most North-Eastern region that borders Slovenia and Austria. I also have a few friends from the region so I know it pretty well.

It is true that our childhoods in the West and the Nordics were not the same as in the former socialist Yugoslavia, so we don’t have the same memories, even if designs are converging for the last few decades. So called brutalist architecture from the 1960s has been given a lot of attention lately, and this various influences often bring out amazing results in the region’s designs. Denmark benefited from it, too, as it has been at the forefront of the hugely impactful neo-Nordic cuisine, spearheaded by René Redzepi, born in Copenhagen to a Danish mother and an Albanian father. René who is a friend, has been very interested in his paternal heritage form the Balkans and he is probably the world’s most influential chef of the past decade, while his Noma is the most celebrated restaurant on the planet. I think this is a great example of the opportunities that are available all over Europe, we just need to apply our creative thinking to it.

“I have to say I actually believe in protectionism if it serves a purpose, not just some personal political agenda. I am all in favour of it when it protects our markets from products that do not share our levels of care for intellectual property and CO2 emissions.”

Is the South-Eastern Europe interesting for you also as a market for Biomega – especially a metropolis like Istanbul?

As a matter of fact Biomega was represented/sold in a shop in Istanbul right when we started. If there are clients who would buy e. g. Cappellini furniture or Baffi kitchens, or whichever classic Italian – or Danish – design, they would also know about Biomega bikes. But it takes a lot more for such a product to be actually used in such a city.

“The power of design has always been to have intuitions. If you base your projects on research, you are not going to come up with anything new, because research can only look back.”

Since you’ve just mentioned some Italian brands: is Italy a market for high end bikes such as Biomega, especially as it is an essentially two-wheel mobility nation?

From the get-go Italy was a place where people intuitively understood Biomega – and even when they didn’t, they would ask great questions, it was amazing. However, the brand was not very successful at integrating -you must accept that racing bike culture is so strong in Italy that people unavoidably look at bikes from a different perspective. They tend to view bikes like most other nations view tuned-up cars with items from race cars. You know, you change this and that, the price is no issue, you have a product of your own “design” that is the most valued. On the other end of the spectrum, city bikes cost nothing in Italy, because there is no decent way to park them, people are not used to take them to their offices, so bikes get stolen all the time. Every city has an area where you can buy great bikes for about 100 euros, and everybody knows it’s been stolen, but nobody makes a fuss because that’s the way it is. You can’t compete with that.

So whatever is left of the higher end market, is very sports oriented. Again there is a parallel with cars: you have the industrialized part of the world where you put your bike on top of your car, drive somewhere, ride a bike there, and then drive back home. This is the case in most of Europe including UK, as well as in the US or Australia – and this is the final stage of mobility evolution. We can observe its early stages in the developing world where people ride bikes because they’re poor. However, the moment when they can afford a moped, they buy one, and so on for a motorcycle and then a car. I remember a city official from Shanghai who told me in 2009: “There will be no more bikes in Shanghai in ten years.” He was very proud of it, because for him it represented that they were getting out of poverty.

And then you have the Germanic part of Europe, Germany, the Benelux and Scandinavia, where bike is an important means of transport, and the decision to use it is based on whether it is practical or not. It has nothing to do with status, even prime ministers would use a bike, if they thought it is more practical.

I’ve seen on the Biomega website that you are already taking pre-orders for the very interesting new model, the BER. When will you launch it?

In the summer, but it is designed exclusively for the American market. It has large 28 inch wheels and battery is hidden in the tube, because we’ve used some brand new battery technology. And thus made it look more like a normal bike. We also referenced a bit the classic American cruiser design which is different than European: you can see it when the top bar goes down at the tail end, which is known from women’s bikes for markets like New York, Amsterdam or Copenhagen.

Another thing where I tried to make it practical is by placing a charger under the handlebar so that the bike is charged from the front. The benefit is that the user does not need to bend down when plugging the bike. It may seem silly or unnecessary at first, but when I design, I often think about cars: they are incredibly simple to use and an important reason for their immense success is their usability. Imagine if you’d have to practically go under the car to charge it – it’s unthinkable, but with bicycles it has become quite normal, as well as that you take the battery off and charge it in your home or office. It’s normal that people adapt to their bike, and not the other way around as with cars. And now with the BER you will stand straight on your feet and just plug the bike – like when you fuel your car.

Honestly it is technically quite difficult, because it involves several cables in the area with moving parts, and probably that’s why it hasn’t been done before … but honestly again, this is where Biomega comes in.

Biomega pioneers urban mobility with timeless, low-maintenance e-bike designs to transform life in urban environments.

Are you considering adapting it to different markets – or planning a whole different model for elsewhere?

You see, when we ceased our work with the Chinese, we had to make a new start, so we made an assessment of all our non-electric models to come to a decision which ones were suitable for an electric version. And in our strategy right now we are focusing on the American market, and later on we will consider the others.

And there is always some adaptation involved, not necessarily to customers’ expectations, but to regulations. The BER would actually be legal in Europe, but many other American electric bikes have the rotating accelerator on the right handle, like a motorcycle, so you regulate speed with your hand. In Europe regulation requires that in a bike speed is generated exclusively by pedalling. When this is the case, you don’t need to wear a helmet, you do not need a licence and so on. On top of the hand accelerator you are also allowed more power in America, 350 kW opposed to 250 in Europe. By the way, there is a 500 kW class in Europe, too, but under much heavier regulation, for example a rider is required to wear a helmet. Having said that, many countries in Europe import e-bikes that are technically not allowed, as apparently they have not yet enforced the regulation.

“I have to say I actually believe in protectionism if it serves a purpose, not just some personal political agenda. I am all in favour of it when it protects our markets from products that do not share our levels of care for intellectual property and CO2 emissions.”

You are a co-creator of the future urban mobility. Can you outline the main trends?

City planners and mobility experts agree that only one means of transport really works for cities, and that’s walking. However, walking is not exactly a means, since it’s not an object of transport but a function of its subject, so it doesn’t really count. The next thing they agree on is that the ultimate type of transport in cities is multi-mobile, e. g. it could be cycling, but probably combined with public transport, car-sharing, walking etc. People figure out individually what’s the best option for this journey at this time of day.

It needs to be said that there are few cities where bicycles are not a good option. Unfortunate exceptions are several cities in India where one actually cycles slower than one walks. The same is true for really spread out cities, such as Detroit, Los Angeles or Berlin. The electric bike has been a game changer in that, because with a regular bike, people would choose it for distances up to 10 km – the number of people choosing a bike would fall only slightly with each kilometer up to 10, and then abruptly. This boundary is extended by 5 km with an electric bike. And in most cities 15 km is quite a lot, so even people from the suburbs start considering cycling.

There are many things that may happen in the future, but the fact is that in Europe we have very old cities and populations are not growing. These cities may still grow a little, but not dramatically, as the share of populations in Europe’s cities is between 50 and 60 %. In Africa, on the other hand, only about 30 % live in cities, so their cities will change a lot – and on top of that by 2050 population is expected to grow by a billion people in Africa and another billion in Asia. Everything will change there, unlike in Europe and the Americas with zero growth, if not negative.

What is new in that part of the world is that their building activity is moving upwards: their cities are becoming more 3-D than in the West where they are more or less flat. It means people are not only travelling horizontally from A to B, but also vertically from Ax to Ay and Bz to Bq. I strongly believe that cities will become more 3-dimensional, and since drones are not of much use in cities, this is the development that will surely influence the usage of bikes in these new urban contexts. My partner Bjarne Ingels has already designed a house in which one can cycle in circles all the way to the top.

All of these things will be integrated in the modern way of living. Let’s take a young Danish family today as an example: if they live in one of the big cities such as Copenhagen or Aarhus, a couple would get together, move in together, then have kids and eventually settle in a family sized appartment somewhere in their 30s. Nowadays when they consider mobility, many skip owning a car, maybe choosing some sharing arrangement for the weekends or so. What they get instead are cargo bikes with 3 wheels and electric power. This is just enough for 2 kids and the groceries, and this is what they actually need for mobility. Cars on the other hand are super expensive and when you want to use them in cities, you spend most of the time in traffic jams. I believe that in the car industry an important segment will become one that competes with those 3-wheel bikes – or something totally different, we need to wait and see as the future tends to bring unexpected developments.

Jens Martin Skibsted designed Nordic tableware HAV with Bjarke Ingels and Lars Larsen for Royal Copenhagen. Inspired by the Danish sea and Japonaiserie, HAV is the result of a 10-year product development. The HAV dinner service takes its name from the Danish word for ‘ocean’ and consists of 9 pieces with subtle fish scale ergonomic ornaments. on the photo: HAV tea pot, 2019.

Faced with this expectations and unknown trends, what is your way of coming up with solutions for known and unknown problems? Do you have a method or is each project a sort of new beginning?

I don’t think that we can predict the future much, therefore our solution is to create it. I never started from thinking that the world needs something, or that I want that something, so let’s do it! The problem with this is above all that when we think that people need something, there is a large probability that other creative types have noticed it, too. So you are not alone in searching for a solution, as thousands of people are having a similar idea. For example when I came up with the idea of a designer city bike in 1998, people were laughing at me as if I were an idiot telling me it’s never going to happen – the thing is it will happen, if you make it happen. It was the same with Bjarne’s house with the bike track: he made it happen.

This has always been the power of design to have intuitions. If you base your projects on research, you are not going to come up with anything new, because research can only look back. I have been on many planning committees for cities and it was incredibly boring, because there are academics and finance people who are only looking at what is already happening. I don’t need a committee to tell me that – I can go out of my house and look around and I will see that. This is the problem with academic approach or linear planning doing incremental projections into the future … it doesn’t add anything new to the future, and what’s more, it even enforces biases from the past. By the way, this is also the reason why artificial intelligence is “racist” – it looks at past patterns.

Marée, meaning tide in French, is a chair series in recycled plastic designed by Jens Martin Skibsted.

Was your new outfit, Manyone, set up to address this issue, too? It seems a bit like “superbands” from the 1970s when people from previously successful bands started playing together.

Yes, it’s a cool way of looking at it. Our goal is to look at the big picture, including the geo-political strategies we’ve discussed at the beginning. Also when you take strategic and digital design, we are the biggest in Europe right now. However, we are also different than other big offices, who work in very specialized teams. What sets us apart is that we put together a deep team for every project and it always works from a strategic point of view. This means we are more focused on corporate change, even transformation or innovation than design in the strictest of meanings.

Headquarters are in Copenhagen, right?

Yes, and we have strong presence all over Scandinavia, too, then we have the UK, Spain is big, Germany is very big, Brazil super big, and the US not so big. Before Covid we were in Shenzhen and in Singapore, too, but I’m not sure how it turned out after the pandemic stress. These situations in offices all over the world tend to change quite quickly.

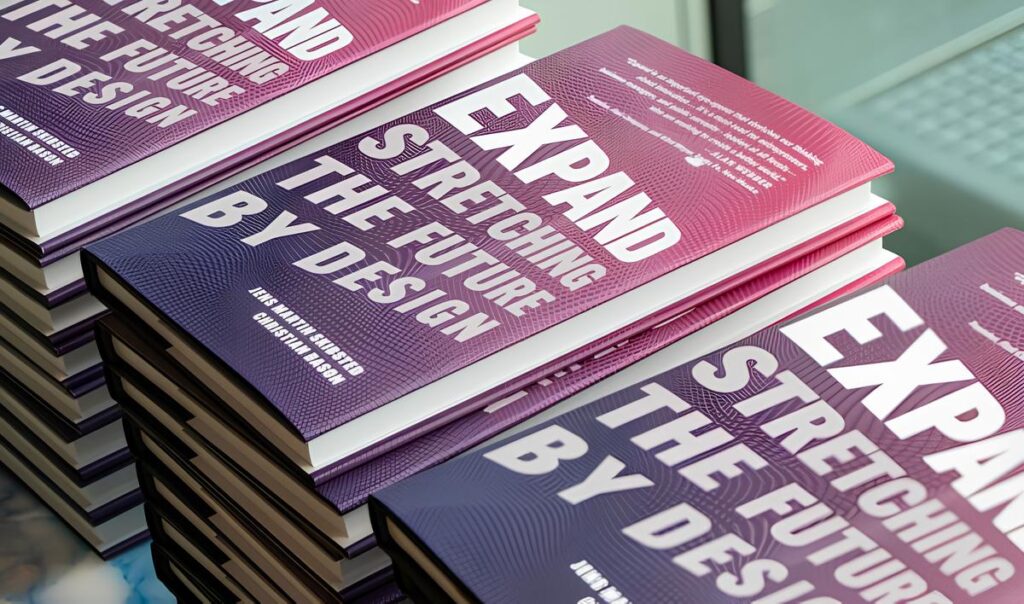

The book Expand – Stretching the future by design written by Jens Martin Skibsted and Christian Bason advocates for “expansive thinking,” a concept that broadens traditional design thinking and human-centered design to address complex global challenges. It emphasizes the need for innovative solutions to issues like climate change, resource scarcity, income inequality, and the impact of AI. By reimagining the scale and scope of design, the book aims to inspire individuals, businesses, and organizations to create sustainable, effective approaches to the world’s most pressing problems.