Aykan Aras, Kutay Kaynak, Can Kayaaslan, Turkey

Nominator: Selçuk Avcı

URBAN CAMOUFLAGE

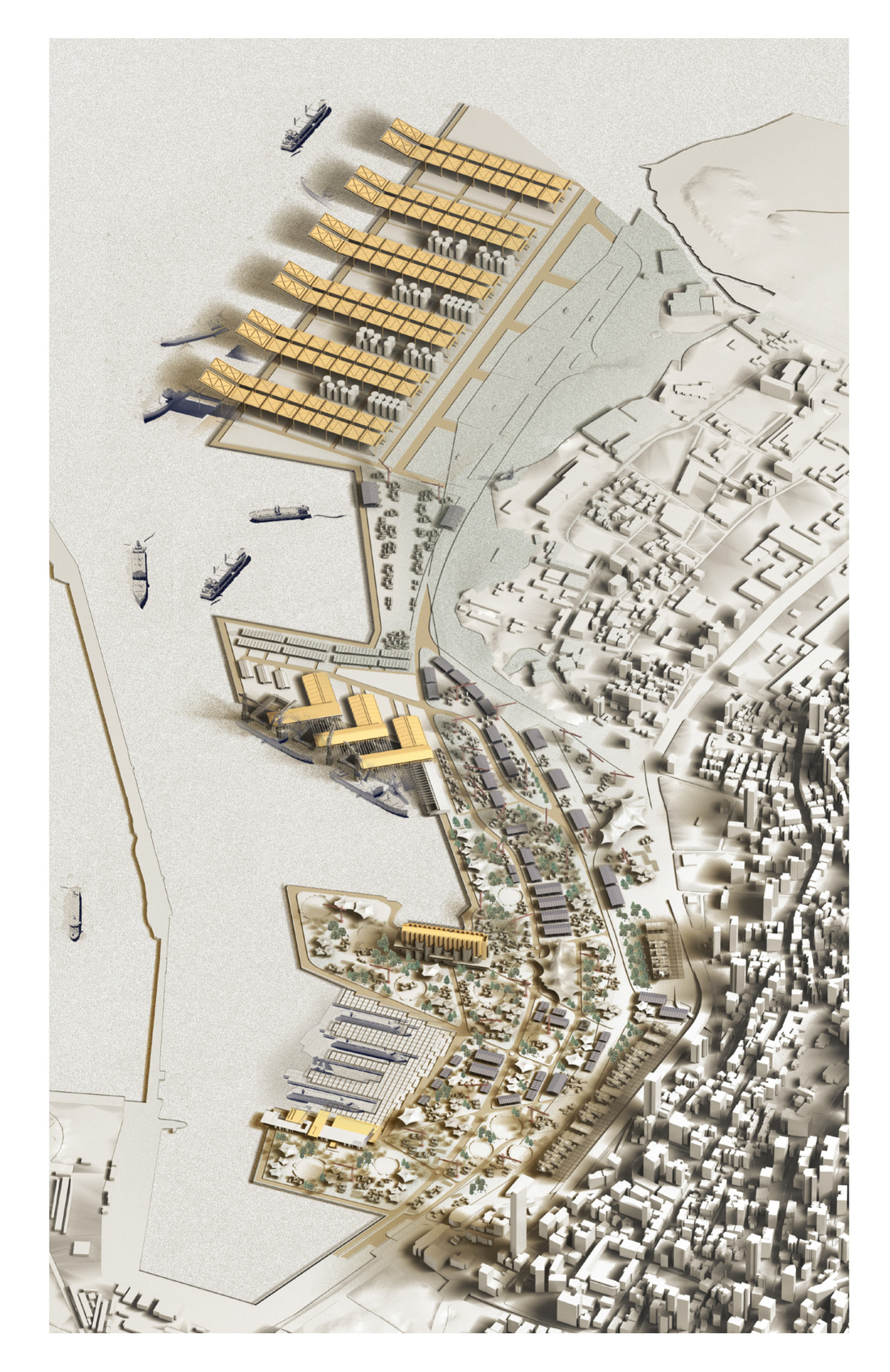

Urban Camouflage reimagines the Port of Beirut as not just a logistical and industrial hub, but as a versatile Freezone capable of meeting any economic or social demand from the city. Resilience in urban systems requires constant harmony with the context and the ability to adapt to changes within that context. The concept of camouflage emerged from research, highlighting Beirut’s familiarity with crises. Notably the Civil War from 1975 to 1990, which left lasting cultural and physical borders, such as “The Green line,” named for the vegetation that camouflaged the region during the conflict.

Camouflage, in this context, refers to synergy with the background rather than hiding. The port must continuously adapt to the ever-changing backdrop of Beirut, reflecting the regeneration of vegetation and landscape over time. This adaptability mirrors the city’s intrinsic resilience, where diverse cultures, religions, and nationalities blend seamlessly—a metaphorical camouflage. This project aims to formalize and enhance Beirut’s innate resilience by establishing a system that consistently and efficiently adapts to evolving needs, promoting flexibility and multi-functionality.

The project categorizes constants and variables. Constants include the Passenger Terminal, Silo Memorial, Shipyard, Container Terminal, Long-term Housing Project, and Tensile Structures, ensuring a future-proof environment capable of responding to needs. Variables, with varying time-frames, encompass daily (Modulor Shoreline Platforms, Shadings), weekly (Light Structures, Containers), monthly (Open Spaces, Temporary Housing Units, Power Stations), and long-term (Markets, Warehouses) elements, providing flexible solutions to handle urban scale problems.

The Passenger Terminal and modular shoreline work together. The Silo Memorial symbolizes the city’s resilience, surrounded by open spaces /gathering zones. The Shipyard, located on the third dock, facilitates ship repairs, contributing to the city’s economic sustainability. Tensile Structures serve diverse purposes, from sports to concerts, enhancing adaptability and inclusiveness. The Long-term Housing Project addresses homelessness both now and in the future emergent situations.

Variable elements combine to form clusters catering to various functions, including Market Areas, Exhibitions, Gathering Zones, and Workshops, promoting an inclusive and collaborative environment. Beirut’s residents can freely assemble these elements to create clusters, even innovating new ones, fostering adaptability and innovation. An easily printable catalog shows all these possible clusters and exemplifies the functions of them.

The catalog features a comic illustrating solutions for festivals or emergencies at the Port, demonstrating the system’s versatility. It is even possible to make overnight transformations, like a shoreline becoming an open-air cinema, facilitated by storing smaller elements in nearby warehouses for swift deployment, showcasing adaptability and resilience.

The 1/4000 site plan is only a possible instant frame from the project. The constants are going to stay as they are, but any variable on the plan might change one day later.

Urban Camouflage develops participatory solutions to city scale problems.

PERA PARADIGMA

Pera [Para]digma

THEORY

1.0 The Crisis of Publicness in Metropolises:

The transformation of cities into metropolises is a long and complex process. As the city’s infrastructure and housing fabric expand, existing structures are redeveloped, and new ones are built. If urban planning and governance are not actively maintained throughout this process, public spaces face the threat of shrinking or disappearing altogether. There are two primary reasons for this. First, the growing population increases the demand for services. As service and infrastructure projects rapidly increase, public spaces—which do not offer a “tangible service”—can easily be overlooked. Additionally, unlike private properties, public spaces are communal goods meant to be accessible and preserved for all. However, individuals with private ownership rights may restrict the use of these once-public areas according to their own interests.

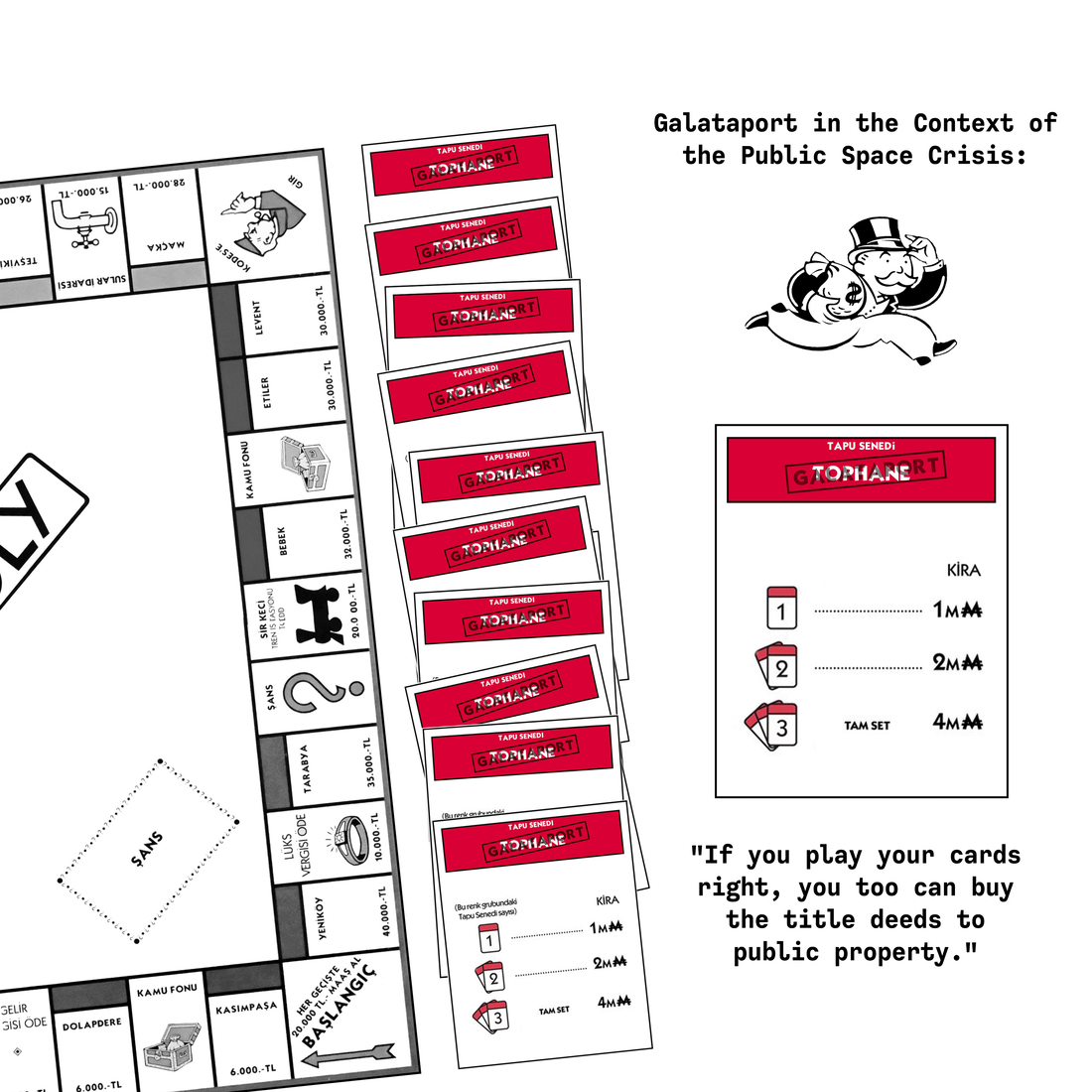

As a result, the accumulated demand for services triggers investment projects. Once urban fragments are claimed—like cards in a game of Monopoly—they turn into investment zones. Public spaces one by one succumb to the hegemony of consumption spaces.

1.1 Nature of the Crisis:

At its core, the crisis stems from a fundamental conflict of values. Advanced civilizations are built upon the principle of placing ideals above needs. However, when public land is opened up for development, individual interests become more appealing than ideals. Anyone with sufficient financial means gains influence over the urban fabric. There is no requirement for these actors to understand the city’s history, culture, or societal dynamics. The quality of decisions is not questioned—if there’s a budget, there’s a project.

1.2 Why Publicness Must Be Protected:

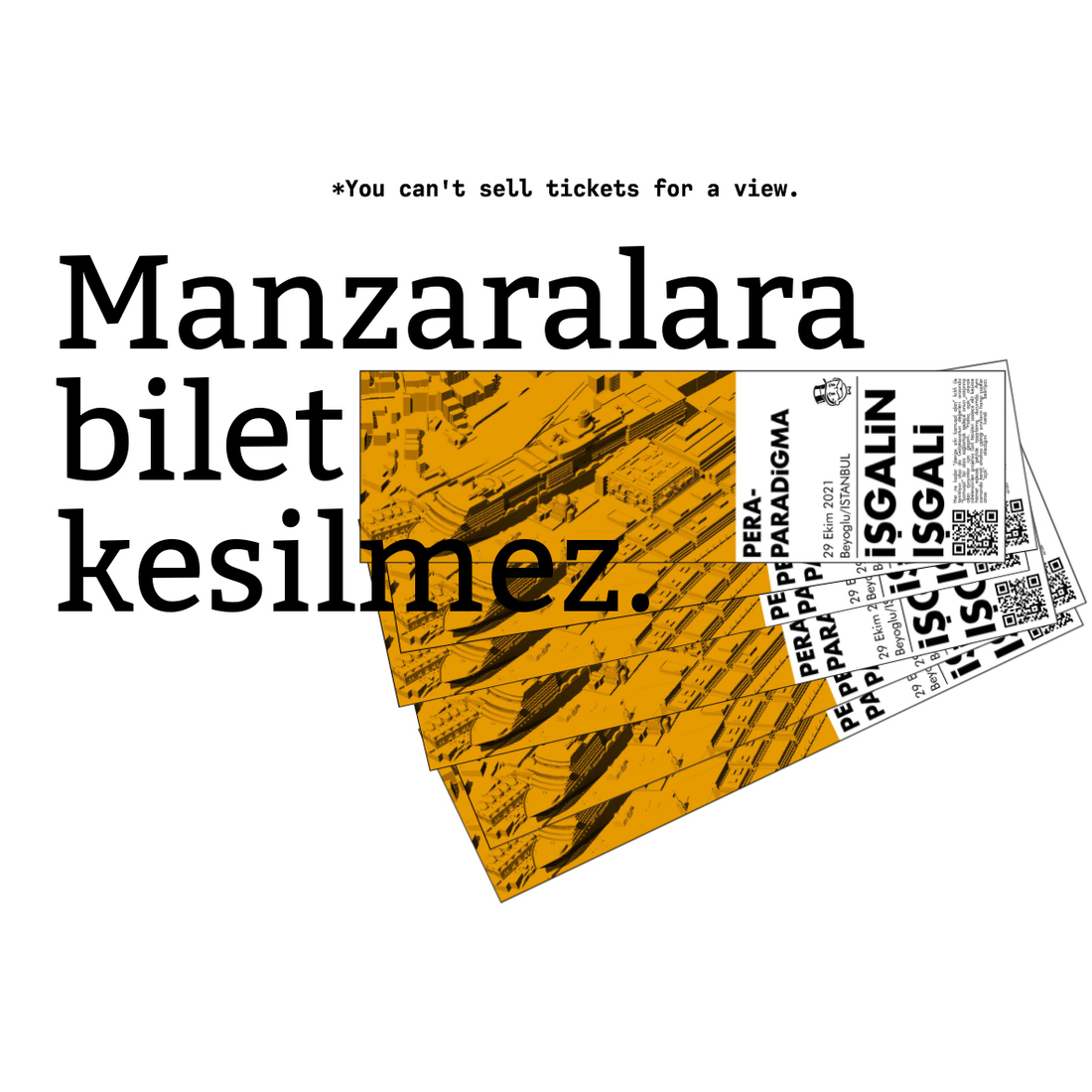

Public spaces are expressions of a city’s and a society’s values. They are symbols of cultural heritage, social life, and collective identity. Their preservation is crucial to maintaining cultural continuity for future generations. A city without public spaces is reduced to residential units and the infrastructures that support them. A space of principle governed by mere necessity contradicts its own essence.

To protect public spaces, one must not expect direct benefits or tangible returns. Seeking material gain from publicness is to once again place needs above principles.

1.3 How to Protect Publicness:

In historically layered cities, public spaces are often structured around squares and monumental open areas. These spaces are not only culturally valuable in themselves, but also form essential elements of the city’s constructed identity. They enrich the city’s image and narrative.

As the city expands and urban life accelerates, these spaces may fall out of step with the times and become inactive. The hegemony of consumption seeks to absorb and convert every underused space into a commercial project. Therefore, protecting these areas means offering them an existence independent of consumption. Spaces that are alive cannot be consumed.

CONTEXT

2.0 Galataport as an Example of the Publicness Crisis:

The project grounds its theory in a tangible example: the Tophane Square and its surroundings. The most visible manifestation of the publicness crisis in this context is the Galataport development. Galataport spans over 100,000 square meters of shoreline from Fındıklı to Karaköy, turning the entire seafront into a touristic port, shopping mall, and office complex. Galataport arrived not only with its buildings but also with its own paradigm. As a result, it reorients the entire context to fit its own narrative—placing needs above principles. The structures surrounding Galataport are now compelled to transform into attractions for a consumer audience. Karaköy, in the quest to appear more appealing, demolishes and rebuilds many of its buildings. The entire shoreline is being reimagined with hotels, restaurants, and other commercial functions.

2.1 A Brief History of the Galata Port and Tophane Square:

The story of what we now know as Tophane Square begins with the Tophane-i Amire. Over 400 years, many buildings were added to the square. By the mid-19th century, Tophane was one of the four gates through which Pera opened to the sea.

In the 1930s, Istanbul’s port administration was nationalized. Warehouses were added in 1958. These warehouses served until the Haliç demolitions began in 1987, after which they became largely inactive. They remained so until rumors of the Galataport project emerged, and this publicly-owned space sat functionless for about 30 years.

PROBLEM

3.0 The Nature/Values of Galataport:

Though marketed as offering “public waterfront space,” Galataport only considers public access when it aligns with its own interests. All of its “publicly accessible” facilities are designed to serve a privileged elite. It also defines its own opening hours, effectively regulating who can access what and when.

3.1 Project Area:

The project encompasses the shoreline from Fındıklı to Karaköy, and the area behind Meclis-i Mebusan Street. The design aims to include every cultural building and surrounding space outside of Galataport. Much of this area has not yet been overtaken by consumption spaces. Tophane Square, in particular, must be reclaimed and protected from Galataport.

3.2 Issues in the Project Area:

The main reasons for the area’s poor functionality are fractured pedestrian continuity and neglected buildings. Identified problems include:

The vehicular traffic on Meclis-i Mebusan acts as a barrier,

The steep topography and poorly maintained landscaping make it hard to reach the shoreline from the park,

Monumental structures like Çavuşbaşı Hamam and Byzantine Wall Ruins remain abandoned,

Tophane-i Amire is not a regular part of public itineraries except during exhibit openings,

Most importantly, Galataport has claimed the only balancing void in this dense area and forces the surrounding area to serve its needs.

In 1999, Istanbul had 470 designated emergency gathering areas. Despite the population nearly doubling, this number has dropped to 77. In the event of a major earthquake, this densely populated area will need more accessible open spaces—spaces that remain open to people at all hours.

SOLUTION

The project adopts four main strategies to revitalize existing structures:

Redirecting 570 meters of vehicular traffic on Meclis-i Mebusan underground, turning the street level into a continuous allee,

Connecting the Artisan’s Park, Tophane-i Amire, and Çavuşbaşı Hamam within a unified landscape design that flows toward the shore,

Creating an archaeological route around the Byzantine ruins and the Çavuşbaşı Hamam,

Redesigning the existing landscape around Tophane-i Amire.

Following these interventions, the project takes a stand against Galataport’s intrusive attitude by reclaiming Tophane Square. It redefines and raises Galataport’s perimeter walls, isolating it within its own exclusive world. Access points are reimagined as watchtowers integrated into these elevated boundaries. While critical of the Istanbul Modern building’s role in blocking the square’s connection to the sea, the project reclaims it into the public realm by purging it of the consumption paradigm.

The remaining surface becomes a vast cultural canvas for citizens to freely engage with historic structures. In a city where people barely have time to notice their surroundings, this canvas offers cultural experience with no expectation in return. It is more than a surface of circulation—it is a platform where diverse public programs can unfold.

“Pera Paradigm” aims to preserve public spaces by freeing them from the paradigm of consumption.

CHRONOTOPOS

History

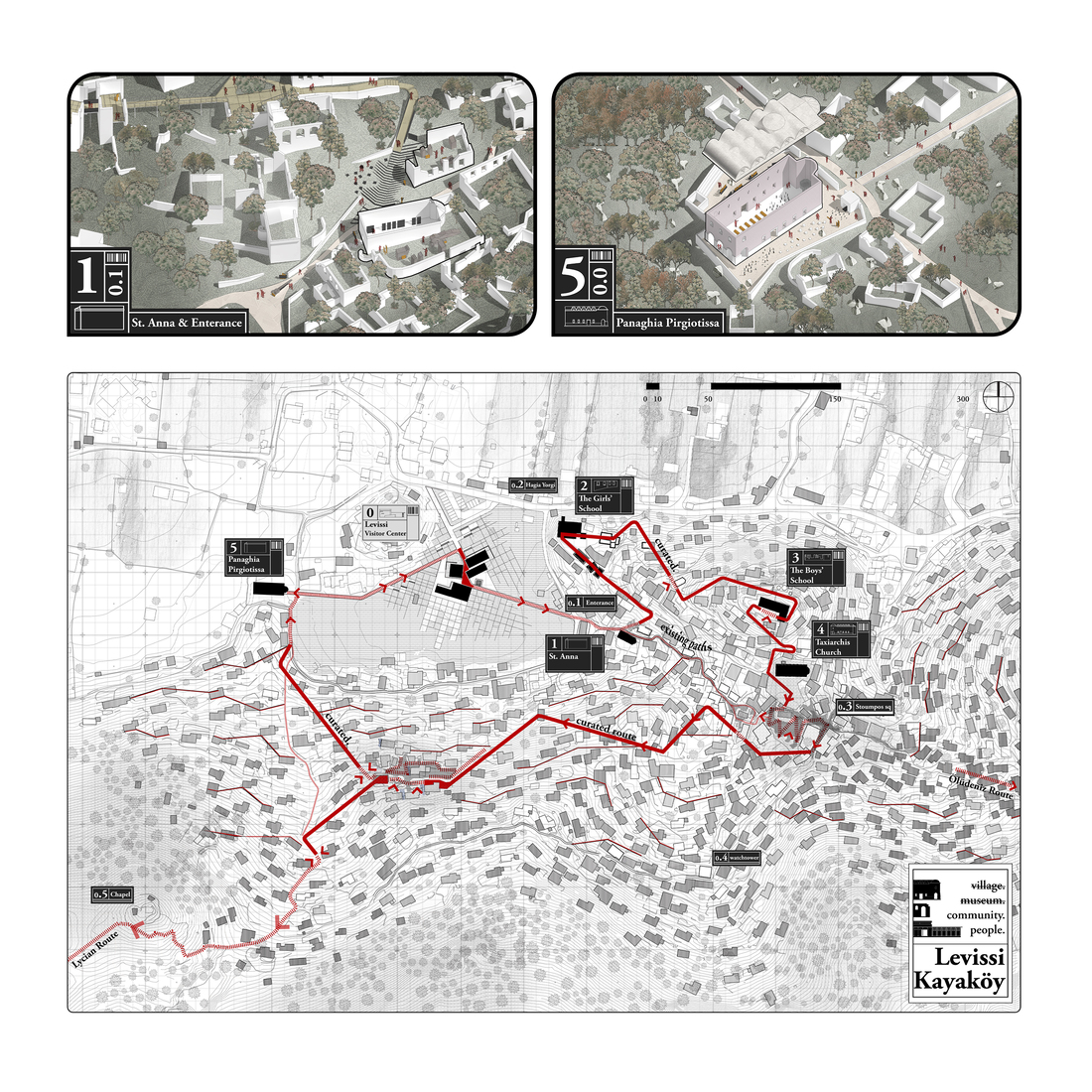

The ruins of Kayaköy, historically known as Levissi, stands as a reminder of the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. During this mandatory migration Greek Orthodox Christians left their ancestral lands causing cultural disorientation and collective trauma. Today, these abandoned ruins capture a part of this history. The design aims to build up on this narrative and create a bridge to the past and a sense of belonging for all visitors, regardless of their origin.

Concept

The project adopts a philosophy of humility, where the design takes a secondary, supportive role, to give more shine to the authenticity of the site. As a "silent bridge" connecting visitors to the ruins and their layered history without overshadowing them. The design invites visitors to engage deeply with Kayaköy’s layered narrative.

Design

Visitor Center:

The visitor experience begins at the original site entrance, maintaining historical continuity. The center comprises three structures built with local materials, reflecting vernacular space-making. The first is an information center providing site management and orientation. The second is an exhibition hall narrating Kayaköy’s history from ancient Lycia to the population exchange. The third is a community space, housing a multifunctional venue for workshops, performances, and events. The events and uses of the space will ve decided by a community council akin to the elderly council of the past village. Adjacent is a “bostan” (traditional community garden) for growing grapes, figs, and olives. The visitor center sets the tone for the experience, serving as the village gateway.

Journey in the Site:

After the visitor center, visitors are free to wander through the site on a semi-curated route. None of the paths are rigid; all are interconnected, creating a flexible route that allows visitors to exit and reenter at various points. Visitors can walk directly through the ruins, navigating the natural terrain with its rough topography. They can explore house ruins' interiors and feel the site's raw essence. Historic roads formerly used by residents are renewed with pavements to ensure accessibility while preserving their original character. Another addition is elevated platforms, walkways above steep and hardly walkable parts of the topography. These walkways aim to make the site accessible and provide a contrasting perspective, enabling visitors to see the village as external observers. This detachment fosters reflective understanding of the site and history.

Visitors can participate in an engaging game, where they search for a specific house of a past resident while reading about their lives. This interactive activity fosters empathy and a deeper connection to Kayaköy’s history.

Revitalized Spaces:

Historical landmarks serve as nodes for visitors to rest, learn history, and interact. Taksiyarhis Church is repurposed as a communal space with open-air exhibitions at its entrance. The boys' and girls' schools and chapel function as cultural and educational hubs, housing displays or activities that reinterpret their historical roles. The village square and its surrounding shops (formerly tailors, butchers, and greengrocers) are revitalized for contemporary communal uses such as cafés, workshops, and craft stores. Small amphitheaters are integrated into some ruins for performances and discussions, allowing visitors to experience the site as both a preserved artifact and a living space.

The project proposes a sensitive design to revitalize Kayaköy, transforming the “ghost village” into a space for learning, reflection, and shared humanity. Immersive experiences, revitalized communal spaces, and respectful interventions aim to maintain Kayaköy as a site of living history.

Aykan Aras, Kutay Kaynak, Can Kayaaslan

hay.axi! // design collective

The term “hay aksi!” in turkish can be translated into the word “oops!” when someone makes a mistake. In our design philosophy we are not afraid to make mistakes and rather open to experiment and widen our abilities.

As the design collective hay.axi we stand as a response to the stiffness often disguised as professionality in architectural scene. We are three 25-year-old architects who produced, experimented, discussed together during our undergraduate years with competitions. Since then, we’ve believed in the power of our collective production. While we’ve received both national and international awards, we view the real reward of hay.axi is working on projects we truly enjoy and care about.

We try to keep the projects fun… for ourselves, above all. We stay far from architecture’s sterile, top-down authoritative design mentality. We are open to allow bottom up methods of space-making and we even allow the projects to get messy. Our approach is critical towards the common architectural practice, but we critize not only with a formal attitude… instead, we criticize with humor and irony. We use these tools to parody established norms and expose their contradictions. It’s a way to create cracks in the surface of the “serious” through which new ideas can grow.

For us, a project is always bigger than the limits of its specific site, a project is a manifesto that exceeds those boundaries. Each project is an attempt to critique a layer of normative architectural practice. And we don’t separate the spatial from the social, or the playful from the political.

As a collective, hay axi! is still in motion, we’re experimenting, failing, learning, and readjusting. We don’t claim to have a fixed method. What we do have is a shared instinct to question, to twist conventions into absurdity (because they are absurd in reality) and to make space for the unpredictable. Whether through competitions, installations, publications, or just conversations, our space-making practice always starts with asking: what if we don’t take this too seriously?

In the worst case all we would say is “hay aksi!”

Contact

+90 534 409 20 49

hayaxi.works@gmail.com