Architects who built the Olympic City, Sarajevo

Dragica and Zoran Doršner belong to the post-war generation of Yugoslavia, and were the architects who built the Olympic City in Sarajevo for the XIV Winter Games in 1984. During their 40 years of practice they have created many different projects, but mainly focused on residential architecture. After the end of the Second World War, the University of Sarajevo started opening its first faculties, among which was the Faculty of Architecture and Construction, which attracted professors from other higher education centres in Yugoslavia.

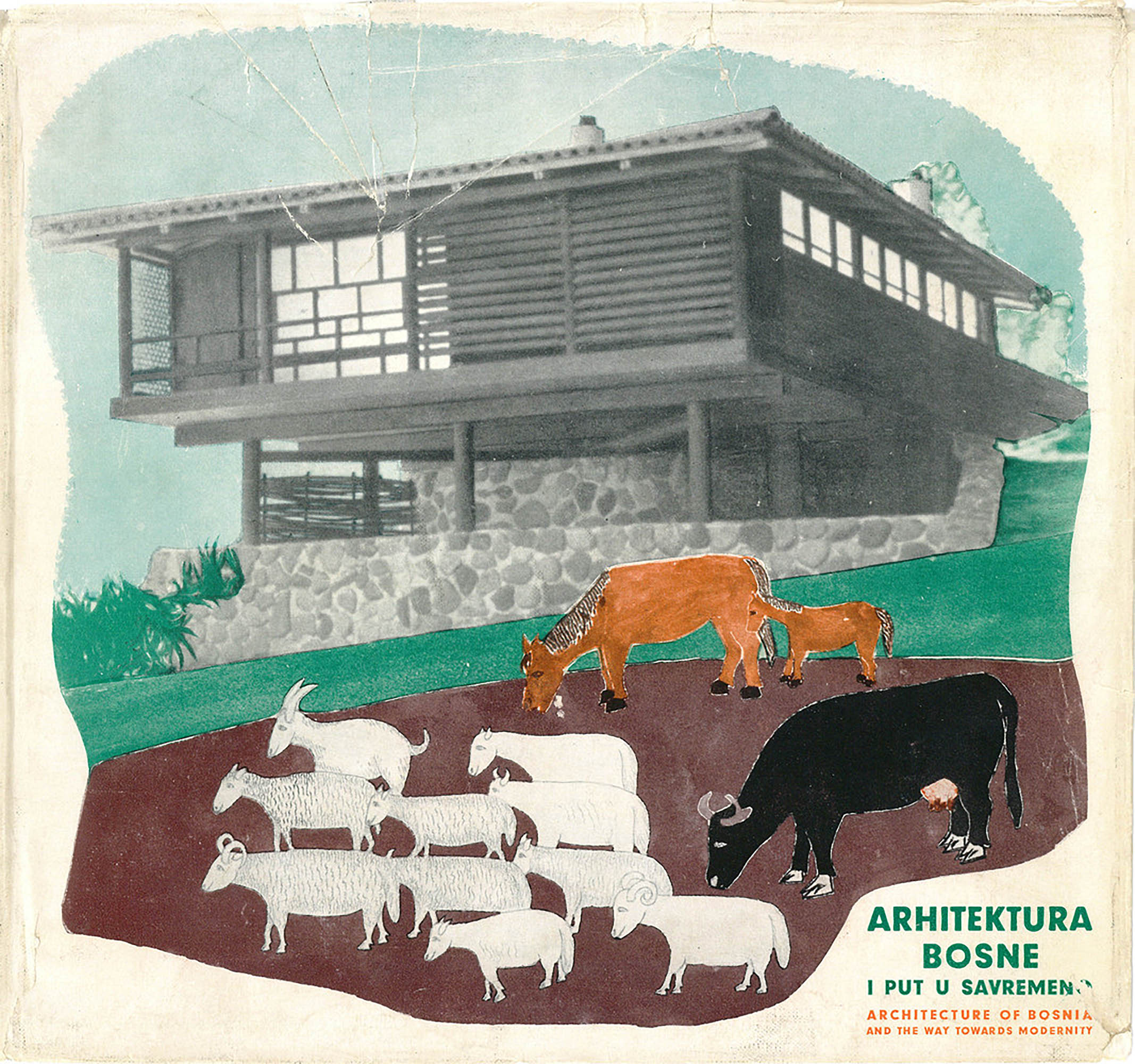

Cover of Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity by Dušan Grabrijan and Juraj Neidhardt (1957); collage, 14 x 14 9/16″ (36 x 37 cm). Image: archive of Juraj Neidhardt

The admission of the first students began in 1954. As early as 1960, the first graduate architects, urban planners, structural engineers, traffic engineers and designers started to get involved in the many offices that had newly opened. Dragica and Zoran were almost among the first students, enrolling in 1956 and 1958, respectively, and graduating in 1962 and 1964. They decided to enrol in a programme that focused on designs for five-year plans of intensive housing construction, which aimed to build 10,000 new apartments every five years in the city of Sarajevo. It is worth emphasising that the city had just 47,000 inhabitants in the first post-war census that was conducted in 1947. But 47 years later, at the time of XIV Winter Olympic Games in 1984, it had some 470,000 inhabitants, or ten times more in just under five decades. A new generation was thus born in Sarajevo, the city and surrounding settlements expanded, factories were built and new jobs were created. We asked them about their work in these years and beyond.

How did you plan the architecture of Sarajevo during the XIV Olympic Games?

Zoran Doršner: As an architect I had already designed and implemented accommodation facilities at the winter centre in Jahorina and participated in the organisation of the international FIS alpine competition Zlata lisica, which – due to the lack of snow on Pohorje, Slovenija – was twice held in Jahorina. The chief urban planner of the city of Sarajevo, the architect Momir Hrisafović, was the man who commissioned me to draw up the spatial plan for the XIV Olympic Games.

And so you visited many Olympic cities?

ZD: Yes, we promptly visited Innsbruck, Grenoble, Courchevel, Chamonix and Garmisch-Partenkirchen. After cordial and well-intentioned discussions we received the planning documentation for their Olympic arenas and remembered their important advice, which can be summarised as follows: “Make sure that you design all the sports facilities as rationally as possible and remember that the final day of the competition is the most important one for you, because then everyday life will continue as did it before the Games.”

What did the Sarajevo Winter Olympic Games change about the cultural context?

ZD: Before the Olympic Games girls in Sarajevo didn’t ski, there was no discussion about women in sport. There is a story about a courageous girl who changed into her brother’s clothes so she could ski. At that time there was no institution in Sarajevo where women could be educated. However, a woman called Adeline Paulina Irby (1831 – 1911), known as Miss Irby, who was a British travel writer and suffragist, founded an early girls’ school in the city. Before then it was possible for a woman in Bosnia to lived closed up in the traditional house with a garden, with total isolation. It was only after the war that Tito gave an order that women and girls also needed to learn how to read.

What was the situation at the time of Sarajevo’s candidacy for Winter Olympic Games?

ZD: It’s worth remembering that before the relevant International Olympic Committee Session there had been violations of the protocol that all international conflicts should be suspended during the Games. Despite this, the US and many other nations boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow, which then caused the USSR to boycott the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. As a result, the International Olympic Committee, under the leadership of Juan Antonio Samaranch, favoured choosing Sarajevo for the Winter Olympics, due to the status of Tito’s Yugoslavia as a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, with the idea this would revive the Olympic tradition of peace and togetherness. And this choice was successful, as many high officials of the International Olympic Committee have on several occasions given a high rating to the organisation of the Games in Sarajevo. One notable story is about how all those working in Sarajevo responded when the Olympic officials asked them for any kind of intervention – it was always: No problem. Samaranch himself stated publicly during the ceremonial extinguishing of the Olympic flame and lowering of the flag at the Koševo stadium that the Sarajevo Games were the most successful yet, and said goodbye to the city with the words: “As this great festival of sport and peace comes to the end, and we must say goodbye to Sarajevo, I am convinced that these Games will remain forever in our hearts and memories. Dovidjenja Yugoslavia, Dovidjenja Drago Sarajevo [Goodbye Yugoslavia, farewell dear Sarajevo].”

How about the atmosphere of the city, how has Sarajevo changed since the 1980s?

Dragica Doršner: The city’s youth in particular accepted the changes. In the winter, instead of heavy coats – as until then there were no mass produced, fashionable clothes in stores – girls and boys began to dress in sporty windbreakers. Foreign languages were learned by many people, and bottles of Coca Cola were sold as a novelty at newly arrived kiosks. A famous hit of Bijelo Dugme, the leading pop band of the time, was “Let’s Go to the Mountains, Because There’s No Winter There!” After Jure Franko’s legendary winning of the Olympic silver medal in the Giant Slalom, a popular saying in the city was “I love Jurek more than burek!” [burek is a traditional food].

What about the 1990s?

ZD: This was a period when the aggressor had no lack of ammunition, and in this a way an enormous “urbicide” was committed. I took many photos of destroyed places and architecture of enormous value. I still can’t believe the amount of hate, and how the Ivan Štraus Elektroprivreda building or old Austro-Hungarian post office building and many others were destroyed.

DD: There has always been a lot of sarcasm in our culture, for example under a graffiti on the renovated post office that said This is Serbia, someone else had written Idiot, this is the post office.

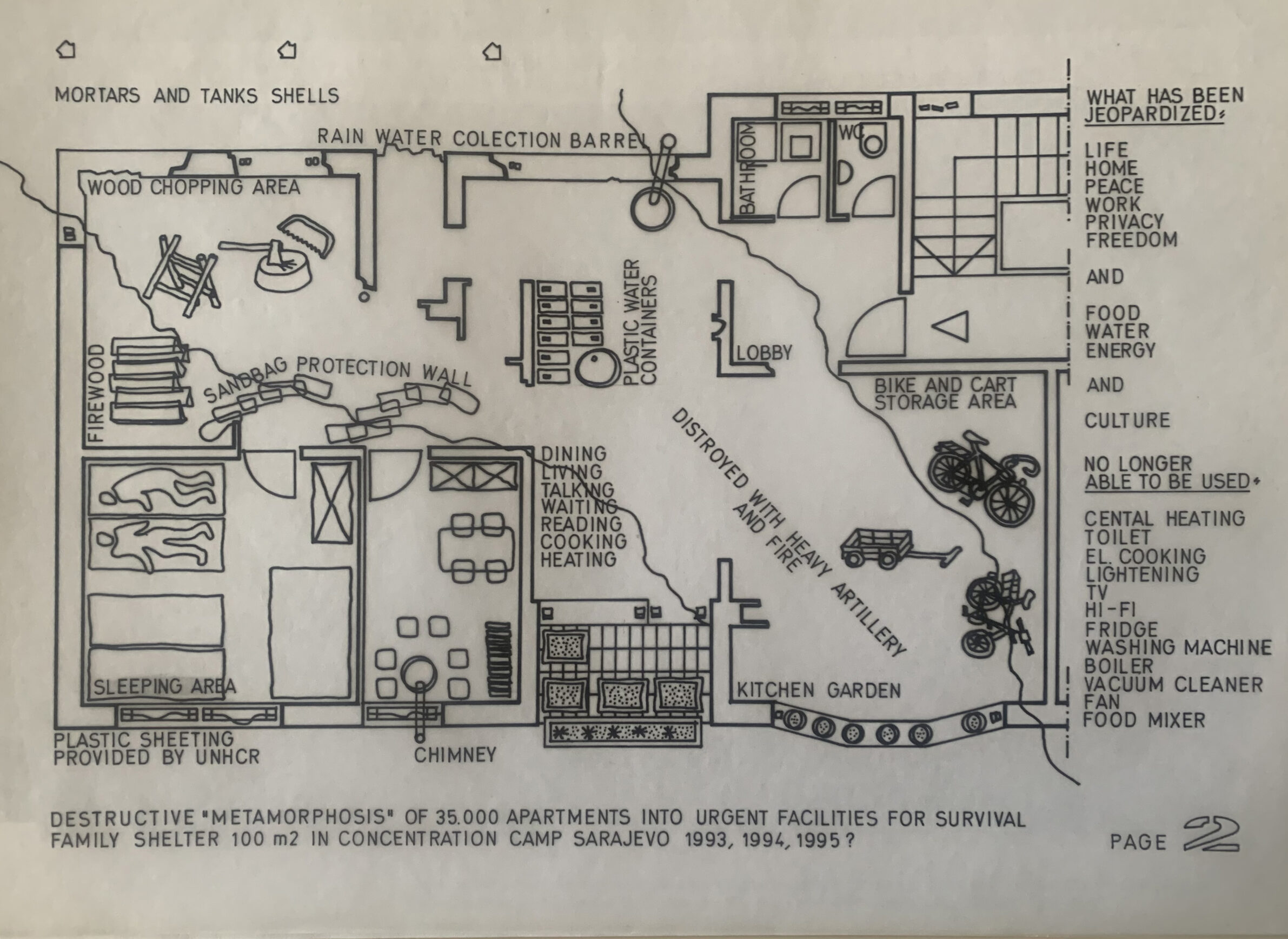

Doršner’s personal photo book, The Urbicide of Sarajevo and Destructive Metamorphosis Plan for Sarajevo, made during the war in the 1990s. Photo: © Boštjan Bugarič, Archive of Zoran Doršner

How did socialism and religion get along?

ZD: It’s a sensitive issue. Religion has been around since Alija Izetbegović started making propaganda. We were all atheists. An interesting change happened when Tito died, as soon the former party officials were sitting in the first row in the mosque. They turned as the wind blows.

DD: During Yugoslavia, religion was not mentioned much, which was the position of the communists, not the Communist Party, and it was not forbidden to practice any religion, although people didn’t make a big deal out going to a church or mosque. With the first democratic elections were held in 1990, new parties with a national character appeared. That’s when a lot of people started going to mosques.

Is there any European influence in today’s Sarajevo?

DD: Sarajevo lives in a very dynamic European rhythm with the vivid architecture of the first so-called “oriental” period, then comes the ambience from the period of Austro-Hungarian empire, followed by a shorter period of socialist realism, accompanied by modern and postmodern buildings. Today’s tourist offer includes a near-mandatory ride on the funicular – a gift from Austria – up Mount Trebević to just below the peak at 1,627 meters above sea level, with a beautiful view of the city and all its variety.

Are there a lot of tourists?

ZD: Yes, all year, and the pedestrian zone in the inner city centre along the main Titova Street is always full of people. The street resembles the Stradun in Dubrovnik, with which we are bound by the medieval charter of the Bosnian Ban Kulin, and with which we also share a similar dialect. As the founder of the first de facto independent Bosnian state, Kulin was and still is highly regarded among Bosnians. Even today Kulin’s time is regarded as one of the most prosperous historical eras, not just for the Bosnian medieval state and its feudal lords, but for the common people as well, and a lasting memory of those times is kept in Bosnian folklore.

What other cultural content is interesting for visitors as well as residents?

ZD: Every summer a lot of international visitors are attracted to the famous Sarajevo Film Festival at the National Theatre, when charming Sarajevo hostesses welcome foreign and domestic visitors. Significant cultural activities also take place during the regular May Collegium Artisticum exhibition of fine artists, sculptors, painters, architects and urban planners, designers, photographers, and graphic artists from all over Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the same even also gives out a lot of awards.

What is the contact with and influence of the Arab world?

DD: Tito’s leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement meant that Yugoslavia had friendly political and business contacts with many different countries around the world, including European nations, the Vatican, and the US, but also many Islamic and Arab countries, all the way to China and Japan. The Yugoslav passport was welcomed all over the world. And today we still see tourists from all over the world, and especially from Islamic countries, who feel at home in the city’s narrow streets and small stores, the kebab shops and cafes of Baščaršija. After the war in the 1990s many humanitarian organisations came from Islamic countries, and some of them acted as missionaries, convincing people to convert to Islam. Many young people converted because the organisations gave a monthly payment, so they did it just to survive. Another arrival, apart from humanitarian organisations, was that of capital from the East. For example, builders and real estate companies from abroad came to Ilidža. This can be seen in bilingualism, with many people speaking Arabic. Settlements were also built for Arab guests outside the city, so that they could stay close to nature around Ilidža.

Doršner's personal photo book, The Urbicide of Sarajevo and Destructive Metamorphosis Plan for Sarajevo, made during the war in the 1990s. Photo: © Boštjan Bugarič, Archive of Zoran Doršner

Who constructs and designs the mosques in Sarajevo?

ZD: According to a legend, the city got its name from Saraj and Ova, the meadow in front of a caravan shelter. After the founding of the city of Sarajevo in the Middle Ages, several significant mosques were built, and later also significant Catholic and Orthodox churches, as well as a smaller number of Jewish and Evangelical temples. It is worth remembering that Jews, after being expelled from Catholic Spain during the Middle Ages, were gladly accepted in Sarajevo where they found refuge and built a synagogue and a temple. At that time Sarajevo wad called the Bosnian Jerusalem. Among the architects of religious buildings in the era of socialist Yugoslavia it is worth mentioning Professor Juraj Neidhardt, who started his first practice in the office of the French architect Le Corbusier. Neidhardt won the first prize for a Catholic religious building in 1970, and as a young associate I had the honour of participating in the final presentation in Zagreb. The final project realisation was created by assistant professor Džemal Čelić. Notable international success was also achieved by Professor Zlatko Ugljen with the mosque in the town of Visoko, for which he was awarded the world-renowned Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Amir Vuk Zec also received an award for the reconstruction of the small mosque in the traditional wooden style in the mountain village Lukomir under the southern slopes of Mount Bjelašnica. I should also mention the realisation of the mosque in Koševsko brdo in Sarajevo, designed by the architects Ahmed and Faruk Kapidžić, with a kindergarten and a playground for children.

Is there still a lot of work to do?

DD: Some buildings were reconstructed after the Balkan Wars in the 1990s thanks to international donations, but of course the reconstruction is still going on. And even if the buildings were not badly damaged there was usually no glass in the windows, so these needed to be covered with nylon and some work still needs to be done here, as with the renovation of roofs.

Do you think Bosnia really sees itself as part of Europe?

DD: It bothers me that we all talk a lot about entering Europe, but we do little to try and achieve it. Bosnia is a very divided country. As a society, we should adapt our laws to those of the EU. We should accept the positive things that can come with being closer to the rest of Europe, but I’m afraid that we will not see it in our lifetimes.

Is there a future for young people here?

DD: Sadly, the answer cannot be a positive one. After the tragic break-up of Yugoslavia and three and a half years of frenzied shelling of the besieged city of Sarajevo, after thousands of citizens were killed, of which at least 1,601 were children, there are still disturbing political, nationalist and religious discussions that make me fear for the future.

Text: Boštjan Bugarič and Martin Reichert

Photographs: Boris Trapara, Boštjan Bugarič, Archive of Juraj Neidhardt, archive of Zoran Doršner