No to discriminatory architecture

Interview with Gabu Heindl

Gabu Heindl is an architect, urban planner and activist who lives in Vienna. As a professor at the Faculty of Architecture she heads the design and research department Architecture Cities Economies – Building Economy and Project Development at the University of Kassel. Her office GABU Heindl Architektur focuses on public space, public buildings, common ownership and non-market housing as well as collaborations in the fields of history politics and critical artistic practice.

SEE magazine #1 /2024

Text: Boštjan Bugarič

Photographs: Katharina Gossow, Gabu Heindl, Lisa Rastl, Klaus Pichler

From 2013 to 2017 she was chair of the ÖGFA – Austrian Society for Architecture. Gabu obtained her doctorate in Vienna and studied architecture in Vienna, Tokyo and Princeton. From 2018 to 2021 she was Visit- ing Professor at Sheffield University with a research focus on the urban commons and subsequently Professor of Urban Design at Technische Hochschule Nürnberg Georg Simon Ohm. From 2019 to 2023 she was a Unit Master at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA), London. Gabu’s architecture says yes and no. Yes to the de- sign of public buildings and infrastructures, cultural and educational buildings. No to chauvinistic, racist or discriminatory architec- ture, to exploitative project proposals, subur- banising single-family houses or speculative buildings. All her projects are positioned in the urban cultural environment, from film, art, theatre and music, to kindergartens, school buildings and social housing.

What relationships in space create chauvinistic, racist or discriminatory architecture?

I’ve written about this on my website, and it’s really a bold statement to remind myself to try and see how architects can be less complicit in the chauvinist building of our environment, in supporting racist housing policies, in engaging in discriminatory or de- fensive urban space design. It’s something that should remind us that we can, as archi- tects, actually ask ourselves to what extent we can contribute to a less a racist, a less chauvinist, and less discriminatory world.

What approach do you follow in creating and defining your projects?

I wish there was one simple path or one way of working. It seems every task, every project somehow asks for its own project development. But I do believe that thinking about project development affects what we do and how we could, in the best sense, ac- commodate the engagement of those whom we work with. I hope that we rarely consider it as working for but rather working with, and hence we side with those who will use the space, which is not always the client. If you design a school or a kindergarten the cli- ent may be sitting in some office in Vienna organising school buildings. But it is the kids and the teachers who we actually have to speak to. That’s also true when it comes

to self-initiated housing, which my office is more and more engaged in: affordable, non- market and co-housing, that especially re- quires a different approach. We do not take a brief and just turn it into architecture, but we are developing the brief with the people involved.

How did living in New York change your perception of the city?

I’ve lived in Tokyo and New York. These were the largest cities that I’ve lived in, and then I also lived in Amsterdam for some time. All of that was important to me, not because it was my ideal lifestyle to be in the biggest cities, but rather I followed much more an idea of moving to places to un- derstand what it’s like to live there. I’ve also experienced life in a small village. And for some time now I’ve been based back in Vi- enna. Now I commute between Kassel and Vienna, and can say that living in these dif- ferent places has helped me to understand this one idea: if a city allows you to live well when it comes to affordable housing, public spaces, schooling, healthcare and so on, then this gives you the freedom to be inde- pendent, freedom to choose what you want to work on and what not. And with regard to all these things, and of all the cities I just mentioned, I think Vienna is the best place.

Whose City? Radical Democracy in Architecture and Urban Planning by Gabu Heindl

What’s special about Vienna?

I have the opportunity to join the activism of some of my friends in Vienna who are fighting against the racist exclusion of social housing and the discriminatory “Viennese first” policy. There are still welfare structures that exist in the city for a lot of people, but we are fighting so they are open to every- one, so that your basic needs do not be- come an existential worry. This is important for everybody. Everyone should be able to choose what they want to engage with, what to work on and who with. Of course, as an architect it’s much easier for me to not en- gage in work I wouldn’t want to do just for the sake of earning money. And yes, I think that this is more difficult in New York, to come back to your earlier question, but then of course too many people in Vienna are still in this situation where they have to decide if they pay the rent or pay for food at the end of the month. That’s really what drives me, to fight for these basic rights for everyone.

What about the rest of the Europe, can you see any indirect discrimination?

For sure there’s discrimination, still East- West, South-North, but also within cities. Every city that we’re working in, in every city that we’re critically mapping we can iden- tify urban areas that have less infrastructure than others, which are less equipped, and at the same time it doesn’t even necessarily mean that they are more affordable. That’s the tricky part, that exploitation comes with the simple need for housing. Affordability doesn’t relate to the quality of space. Yes, we need to speak about the rights to decent housing and a decent life for all the people in Europe – for everyone who’s here and including people who will want or need to migrate to Europe in the future. To combine the social question with the ecological ques- tion means that at the end of the day there’ll be some new distribution, and it also means that if we speak about a less unjust distribu- tion of space, some people will have to actu- ally give up of some of that which they have too much of at the moment – to put it po- litely. That is the hard message that nobody wants to talk about. If we speak about living with less CO2 emissions and sharing more space, then the crucial question is who ex- actly do we ask to give up something? And we’ll certainly not ask those who already live on so much less than others.

Extension of the Kindergarten Rohrendorf near Krems (2008). Photo: © Lisa Rastl

In 2018 we had the opportunity to host you at the conference Collective Hous- ing: New Initiatives in Ljubljana to share different knowledge about cooperative housing, knowledge that is being lost because of being ashamed of ideas that came from Yugoslavia. What pro- jects from Vienna did you present to in Slovenia?

I think every place itself has a history of common ownership models, and I think what we’re planning at this moment with my dear university colleagues, such as Iva Marčetić at the Master Studio in Kas- sel, is to really look into different common ownership models in the different histories of different places. It’s not about bringing a Viennese model to some other places or a successful cooperative logic that is established somewhere to be imported somewhere else. Instead, in a way all cities can relate to their own alternatives in his- tory, or maybe sometimes the supposedly lost history that they could actually revive. I’m interested in how the logic of common ownership and common ways of organising, and also governance, or questions of how to produce things together, have existed in a specific place. And there I would say we should much rather share the histories of re- viving, of sharing experiences, of how some of this knowledge has been lost and how it also can be recovered, further re-invented, critically inherited. I studied the case of Red Vienna, which is a case of communal own- ership housing models with a supposedly successful continuity, and even there I found some alternatives in this already alternative history. If we consider Red Vienna to be an alternative case to so many cities with neo- liberal housing development, then even par- allel to this public housing story you could find even more emancipatory, more feminist, more community-organisation than top- down housing provision. I am very happy that as an architect I can support activists and groups to self-initiate projects that have another idea about solidarity rather than just the provision of standardised housing. I con- sider our work as a reviewing of some of the historic emancipatory notions. But we can also see such a powerful drive in so many cities, especially if you think of the politics of all these powerful movements in Belgrade, Zagreb and so many other places in South- ern Eastern Europe. So I think people in Vi- enna can learn a lot from these places, and vice versa.

How do you see the work of women in architecture?

I’m really sad this still has to be a question – because it would hardly be one if there was gender equality – and I’m very grate- ful that a lot of my colleagues are actually working on this still urgent matter. I’ve seen my feminist engagement in architecture in looking into the issue of structural inequality, not so much in terms of architects but more generally in the structural spatial injustices between men and women, and even more

No to discriminatory architecture

Interview with Gabu Heindl

SEE magazine #1 /2024

Text: Boštjan Bugarič

Photographs: Katharina Gossow, Gabu Heindl, Lisa Rastl, Klaus Pichler

Gabu Heindl is an architect, urban planner and activist who lives in Vienna. As a professor at the Faculty of Architecture she heads the design and research department Architecture Cities Economies – Building Economy and Project Development at the University of Kassel. Her office GABU Heindl Architektur focuses on public space, public buildings, common ownership and non-market housing as well as collaborations in the fields of history politics and critical artistic practice.

From 2013 to 2017 she was chair of the ÖGFA – Austrian Society for Architecture. Gabu obtained her doctorate in Vienna and studied architecture in Vienna, Tokyo and Princeton. From 2018 to 2021 she was Visit- ing Professor at Sheffield University with a research focus on the urban commons and subsequently Professor of Urban Design at Technische Hochschule Nürnberg Georg Simon Ohm. From 2019 to 2023 she was a Unit Master at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA), London. Gabu’s architecture says yes and no. Yes to the de- sign of public buildings and infrastructures, cultural and educational buildings. No to chauvinistic, racist or discriminatory architec- ture, to exploitative project proposals, subur- banising single-family houses or speculative buildings. All her projects are positioned in the urban cultural environment, from film, art, theatre and music, to kindergartens, school buildings and social housing.

What relationships in space create chauvinistic, racist or discriminatory architecture?

I’ve written about this on my website, and it’s really a bold statement to remind myself to try and see how architects can be less complicit in the chauvinist building of our environment, in supporting racist housing policies, in engaging in discriminatory or de- fensive urban space design. It’s something that should remind us that we can, as archi- tects, actually ask ourselves to what extent we can contribute to a less a racist, a less chauvinist, and less discriminatory world.

What approach do you follow in creating and defining your projects?

I wish there was one simple path or one way of working. It seems every task, every project somehow asks for its own project development. But I do believe that thinking about project development affects what we do and how we could, in the best sense, ac- commodate the engagement of those whom we work with. I hope that we rarely consider it as working for but rather working with, and hence we side with those who will use the space, which is not always the client. If you design a school or a kindergarten the cli- ent may be sitting in some office in Vienna organising school buildings. But it is the kids and the teachers who we actually have to speak to. That’s also true when it comes

to self-initiated housing, which my office is more and more engaged in: affordable, non- market and co-housing, that especially re- quires a different approach. We do not take a brief and just turn it into architecture, but we are developing the brief with the people involved.

How did living in New York change your perception of the city?

I’ve lived in Tokyo and New York. These were the largest cities that I’ve lived in, and then I also lived in Amsterdam for some time. All of that was important to me, not because it was my ideal lifestyle to be in the biggest cities, but rather I followed much more an idea of moving to places to un- derstand what it’s like to live there. I’ve also experienced life in a small village. And for some time now I’ve been based back in Vi- enna. Now I commute between Kassel and Vienna, and can say that living in these dif- ferent places has helped me to understand this one idea: if a city allows you to live well when it comes to affordable housing, public spaces, schooling, healthcare and so on, then this gives you the freedom to be inde- pendent, freedom to choose what you want to work on and what not. And with regard to all these things, and of all the cities I just mentioned, I think Vienna is the best place.

Whose City? Radical Democracy in Architecture and Urban Planning by Gabu Heindl

What’s special about Vienna?

I have the opportunity to join the activism of some of my friends in Vienna who are fighting against the racist exclusion of social housing and the discriminatory “Viennese first” policy. There are still welfare structures that exist in the city for a lot of people, but we are fighting so they are open to every- one, so that your basic needs do not be- come an existential worry. This is important for everybody. Everyone should be able to choose what they want to engage with, what to work on and who with. Of course, as an architect it’s much easier for me to not en- gage in work I wouldn’t want to do just for the sake of earning money. And yes, I think that this is more difficult in New York, to come back to your earlier question, but then of course too many people in Vienna are still in this situation where they have to decide if they pay the rent or pay for food at the end of the month. That’s really what drives me, to fight for these basic rights for everyone.

What about the rest of the Europe, can you see any indirect discrimination?

For sure there’s discrimination, still East- West, South-North, but also within cities. Every city that we’re working in, in every city that we’re critically mapping we can iden- tify urban areas that have less infrastructure than others, which are less equipped, and at the same time it doesn’t even necessarily mean that they are more affordable. That’s the tricky part, that exploitation comes with the simple need for housing. Affordability doesn’t relate to the quality of space. Yes, we need to speak about the rights to decent housing and a decent life for all the people in Europe – for everyone who’s here and including people who will want or need to migrate to Europe in the future. To combine the social question with the ecological ques- tion means that at the end of the day there’ll be some new distribution, and it also means that if we speak about a less unjust distribu- tion of space, some people will have to actu- ally give up of some of that which they have too much of at the moment – to put it po- litely. That is the hard message that nobody wants to talk about. If we speak about living with less CO2 emissions and sharing more space, then the crucial question is who ex- actly do we ask to give up something? And we’ll certainly not ask those who already live on so much less than others.

Extension of the Kindergarten Rohrendorf near Krems (2008). Photo: © Lisa Rastl

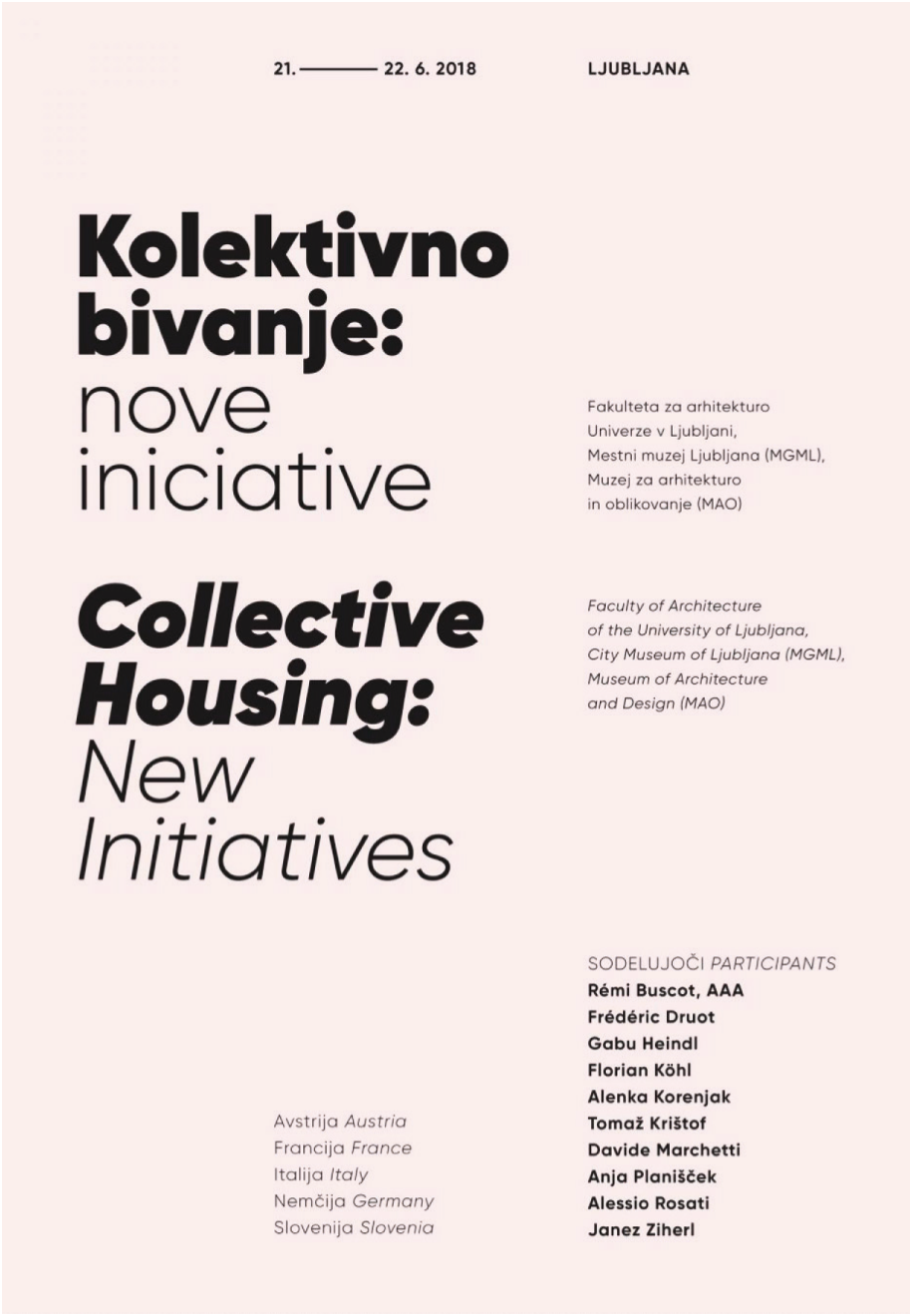

In 2018 we had the opportunity to host you at the conference Collective Hous- ing: New Initiatives in Ljubljana to share different knowledge about cooperative housing, knowledge that is being lost because of being ashamed of ideas that came from Yugoslavia. What pro- jects from Vienna did you present to in Slovenia?

I think every place itself has a history of common ownership models, and I think what we’re planning at this moment with my dear university colleagues, such as Iva Marčetić at the Master Studio in Kas- sel, is to really look into different common ownership models in the different histories of different places. It’s not about bringing a Viennese model to some other places or a successful cooperative logic that is established somewhere to be imported somewhere else. Instead, in a way all cities can relate to their own alternatives in his- tory, or maybe sometimes the supposedly lost history that they could actually revive. I’m interested in how the logic of common ownership and common ways of organising, and also governance, or questions of how to produce things together, have existed in a specific place. And there I would say we should much rather share the histories of re- viving, of sharing experiences, of how some of this knowledge has been lost and how it also can be recovered, further re-invented, critically inherited. I studied the case of Red Vienna, which is a case of communal own- ership housing models with a supposedly successful continuity, and even there I found some alternatives in this already alternative history. If we consider Red Vienna to be an alternative case to so many cities with neo- liberal housing development, then even par- allel to this public housing story you could find even more emancipatory, more feminist, more community-organisation than top- down housing provision. I am very happy that as an architect I can support activists and groups to self-initiate projects that have another idea about solidarity rather than just the provision of standardised housing. I con- sider our work as a reviewing of some of the historic emancipatory notions. But we can also see such a powerful drive in so many cities, especially if you think of the politics of all these powerful movements in Belgrade, Zagreb and so many other places in South- ern Eastern Europe. So I think people in Vi- enna can learn a lot from these places, and vice versa.

How do you see the work of women in architecture?

I’m really sad this still has to be a question – because it would hardly be one if there was gender equality – and I’m very grate- ful that a lot of my colleagues are actually working on this still urgent matter. I’ve seen my feminist engagement in architecture in looking into the issue of structural inequality, not so much in terms of architects but more generally in the structural spatial injustices between men and women, and even more

intersectionally with regard to class and race next to gender. So I always try to think of these categories together. We need to look at what is happening in terms of acces- sibility to space, in terms of simply the pos- sibility or rather impossibility of taking part in anything, starting with being able to live peacefully and affordably, but also being to take part in public space, to partake in the making of our cities, if we relate that to Henri Lefebvre, for instance. At the University in Kassel we are currently working on a pro- ject where we look into the interrelationship between the gender wealth gap and home ownership or freehold flats. The gender wealth gap is even wider than the gender pay gap. Looking at the trend or rather the political project of buying a home shows how with home ownership the structural in- equality between men and women increas- es. With little chance for wealth acquisition some people will never be able to afford to buy a house or apartment. However, what we want to do is not to argue for every woman to become as wealthy as some men are, but rather radically critique the idea of wealth and the constructed goal of owning an apartment. Instead, we propose to look further into common ownership housing, or “social property” – and this comes again back to rental housing. We would like to develop good arguments against the idea of owning a home. With owning I mean to

The Promises of Modernist Premises: Pool Trakiya is a collective re-appropriation of a deserted pool as communal outdoor centre in Plovdiv, Bulgaria (2016).

Photo: © Gabu Heindl, A conference about social housing in Ljubljana, Slovenia in 2018 with Gabu Heindl, Frédéric Druot, Rémi Buscot (Atelier d’architecture autogérée), Florian Köhl, Davide Marchetti, Alessio Rosati, Alenka Korenjak, Anja Planišček

have a property title to something, but of course what we need to do is to formulate the idea of “owning” as belonging, in terms – slightly following Hannah Arendt there – of a space, an apartment, a home being yours: this means that you have the key, you have security, you have a space you belong to and that you give a measure of character to. You will be able to live there and will not be thrown out, and the rental price will not grow erratically. So in this sense we need to gain precision in distinguishing between the concept of property and, on the other hand, the belonging to a place and all the security which should come with that.

We are strongly inspired by Silvia Federici, who in the 1970s with a whole group of femi- nists supported the struggle for wages for housework. But she took the struggle even further by coining the slogan wages against housework, which turned the fight around and said something like “we don’t want to be paid for housework, we want to change the logic of who is doing what sort of work and how we could share it completely different- ly.” Again, I think the history of feminism has so much to offer to us, such as, for instance, how with similar critical thinking we can take another turn and understand spaces within the logic of capitalism, or also within the logic of the white propertied male subject.

How do you see yourself as an educator?

The reason why I like to teach is because it’s beautiful to see this young generation of students be so political again. I can see how my generation has to keep up with the radicality of the demands of these kids. It’s enormously empowering to see how some paradigm changes as well as systemic and radical rethinking could really happen. Our students demand an end to demolition, they are demanding the end of new construction as long as there are so many vacant prop- erties, as long as there is so much unused space. With this powerful force we are chal- lenged to completely rethink what architec- ture is about. How can we engage in the world without destroying so much, without using so much energy, without architecture being such a big part in emissions and even more all the waste production? When I took over the chair of Architecture Cities Economies – Building Economy and Project Development, I realised that this is exactly where we need to be at this moment: to re- ally redefine who we are and what project development does, how it can contribute to more justice, but also support solidarity and circular economies, rebuilding instead of new building, concepts of using instead of owning. And if we really need to construct

Outside in Prison is an art project in a men’s prison courtyard in Krems (2011). Photo: © Gabu Heindl

Exhibition at Austrian Museum of Contemporary History Vienna, (2021-2023) Disposing of Hitler: Out of the Cellar, Into the Museum. Photo: © Klaus Pichler

something new then we should aim to max- imise the social and ecological benefits – and that’s already a big task, which we need to define properly. We also need to think about the economy in a more diverse way. So I hope that our students don’t just think about the financial economy, but also of the concept of the commons, of feminist or solidarity economies. There are so many other concepts of economy which have to come to the foreground again. And since my department in its very name includes the term “project”, which is such a modernism- driven concept, we need to rethink what a project is, and the same applies, of course, to the term “development”. How can you conceptualize development without growth? And then, finally, and very simply, you have to ask: who is a project developer? I’d love to empower students, and also activists – as that’s what I do in my architectural work – or, more generally, to make people understand that they can all be project developers. The agent you have in mind when you speak of who develops projects should not be some René Benko-style aggressive capital-powe player – quite the opposite. We have to de- mocratise the idea of project development with regard to the housing crisis and the looming climate catastrophe. It’s great that the University of Kassel gives me a chance to do this, as it’s an important moment to engage with and contribute to this change.

What about creativity?

If I speak about the concept of a building economy, people think that architecture doesn’t need any creativity anymore. But I’d really like to emphasise that to repair all our built environment and to make it a liveable environment for everyone, and every spe- cies, is a task that certainly involves crea- tivity: we have to use an endless amount of creativity and design so many beautiful things. We shouldn’t worry that to work on a socio-ecological transformation wouldn’t call upon enough of our creative energy – instead, let’s share our creativity to make a more caring and just world.

SEE magazine #1 /2024