Interview with Ana Dana Beroš

Under the umbrella of the LINA platform, the programme From Care to Cure and Back was initiated by Ana Dana Beroš in collaboration with the Association of Architects of Istria (DAI-SAI). “To treat, cure and give care again” is the idea behind this programme, says Ana Dana, who stresses how important it is to deal with experimental publishing practices in architecture. She is referring to how care was and is missing in formal architecture education, in the form of a humanistic way of thinking, as well as asking background questions, an approach which primarily concerns the users of buildings. As the state developed in Croatia following its independence, public projects fell into the background, and it became clear that we must learn from our own history, repair, preserve and take care together, and not build unnecessarily.

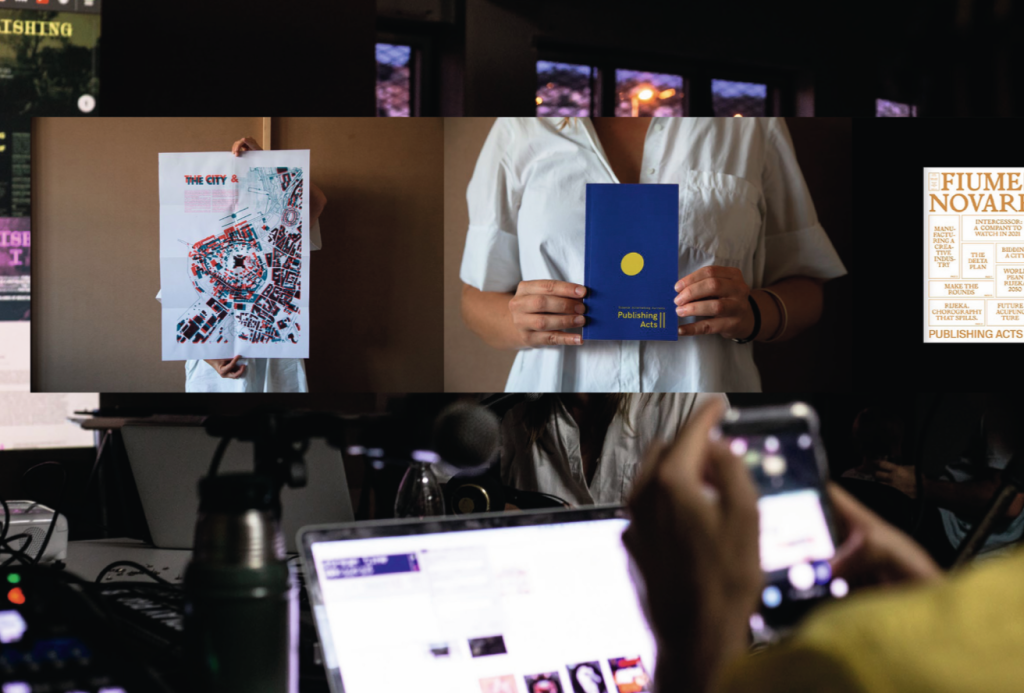

Publishing Acts I-II-III (2017-2020). Photo: © Matija Kralj Štefanić, collage Ana Dana Beroš

How will architecture change in the future?

It will change drastically. I ask myself all the time is it ethical to build anymore, or should we be focusing on “the Great Repair” of the broken world? Or is it more a case of broken architecture, or a broken mankind, or the creation of a more than human environment? These questions arise because for more than half a century we have been witnessing the capitalist modernity, with its emphasis on innovation, growth, and progress, its economic system based on consumerism, waste and profligacy, which has led to a ruthless exploitation of humans and nature. Architecture has played a huge part in this, as the statistics on greenhouse gas emis- sions and construction and demolition waste prove. As a counter-strategy to capitalism’s creative destruction, we should focus on the issue of repair, in which nurturing and main- tenance should become the key strategies for such action. And this is not just my idea, as the notion of care in architecture has been part of many international exhibitions, starting with the exhibition Critical Care Architecture and Ur- banism for a Broken Planet at the Architek- turzentrum Wien curated by Elke Krasny and Angelika Fitz, then the term “the Great Repair” was put forward by Milica Topalović and her team at ETH, and there are also the so-called pedagogies for a broken planet. I see the future in developments such as these.

What does your critical spatial practice include?

My critical spatial practice has components of artistic research, documentary filmmak- ing, curating, publishing/broadcasting, exhi- bition design, activism and post-disciplinary de-schooling. This is work that overlaps, diverges, converges, runs in parallel, in cir- cles, and in many cases came before and goes beyond. A whole multitude of practi- tioners and theorists have been developing work in an expanded field such as this, quite different perhaps from the one Rosalind E. Krauss identified in 1979. The term critical spatial practice was coined by the theorist Jane Rendell in the 2000s as a helpful way 213 of describing projects located between art and architecture, that both critiqued the sites into which they intervened as well as the disciplinary procedures through which they operated. Taking into account the wide spectrum of intellectual fields close to architecture and space – from urban anthropology to human geography – I consider connecting architecture with feminist theory crucial for the development of critical spatial practices. Gender-based analysis of architecture, its multiple forms of representation, where sub- jects and spaces are viewed as performa- tives and constructs, is aimed primarily at questioning the world around us. Moreover, critical spatial practices are necessarily self- critical and aim to change society, in con- trast to orthodox architectural practices that seek to maintain and strengthen the existing social and spatial order of inequality.

How is the LINA platform important for the development of an architecture of care?

I started working on the architecture of care based on the concept of pedagogies of care within the predecessor platform to LINA, the Future Architecture Platform. The Publishing School: Pedagogies of Care was an exploration of how we learn and produce knowledge collectively through emancipa- tory practices of care. The programme built upon the three experimental editorial workshops, titled Publishing Acts, and their collective efforts in shaping extraordinary publications, unlikely publics and unortho- dox spatial imaginaries.

Can radio once become again a media for architecture, as in the time of Frank Lloyd Wright, and how do you work with it?

Regarding radio as a powerful architec- tural tool, or the other media that architec- ture uses, I agree with those who say that architecture has now become transmedial. We don’t create only in the offline world, in the brick and mortar world, but in the on- line sphere as well. All media are useful, or rather necessary, to attain the goals of ar- chitecture. I’ve been involved in radio for a very long time, as I’ve been working for the Croatian radio station HR3, and have been developing the radio schools with artists during the Pedagogies of Care project. Like our colleagues from dpr-barcelona, whose motto is Books are louder than bombs, we say that radio is louder than bombs.

Besides radio, you also work in docu- mentary film. What can you tell us about that?

My documentary work is dedicated to both architecture and migration. Within the Croatian Architects’ Association I have been leading, then co-leading a documentary project Čovjek i prostor (Man and Space) and working as a scriptwriter on long fea- ture documentaries dedicated to the life and work of various laureates. In pluriannual research on the relational reading of migrant bodies and migrant ter- ritories, conducted together with my artistic partner and cinematographer Matija Kralj Štefanić, we have been departing from non- representational theories, the practices of witnessing that produce knowledge without contemplation. The experimental documen- tary trajectory builds on previous investi- gations in the Mediterranean: in reception camps (Contrada Imbriacola, Lampedusa), migrant hotspots (Moria, Lesbos), makeshift camps (Idomeni, Greece), urbanised camps (Dheisheh, Palestine), city refugee sites (Mardin, Turkey), and more recently in the Balkans, where we live. We have refined our methods of producing critical, nonrepresentational images, and of gathering and documenting evidence found in borderscapes, in order to make a transmedial and migratory archive, a border documentarism, that is in constant articula- tion. After the pandemic, from mute images of migrants and what they have left behind that speak for themselves, we started creat- ing a polyphony of protagonists of migrant origin and those involved in the No Border Network in a documentary series Three- Voiced: Stories on the Move, broadcast in Croatia. As a contemporary response to the rise of fascism in Europe, in an era of fetishising borders and the territorialisation of bodies, it was crucial to start resonating in a new voice and new register on topics that are not heard – or rather are systematically not listened to – in our societies. This is just one of many attempts at confronting struc- tures of silencing, asking: Can we, through collective vibration, transform silence into a path of newfound hope and solidarity?

How has Intermundia opened up the important topic of transmigration in Europe?

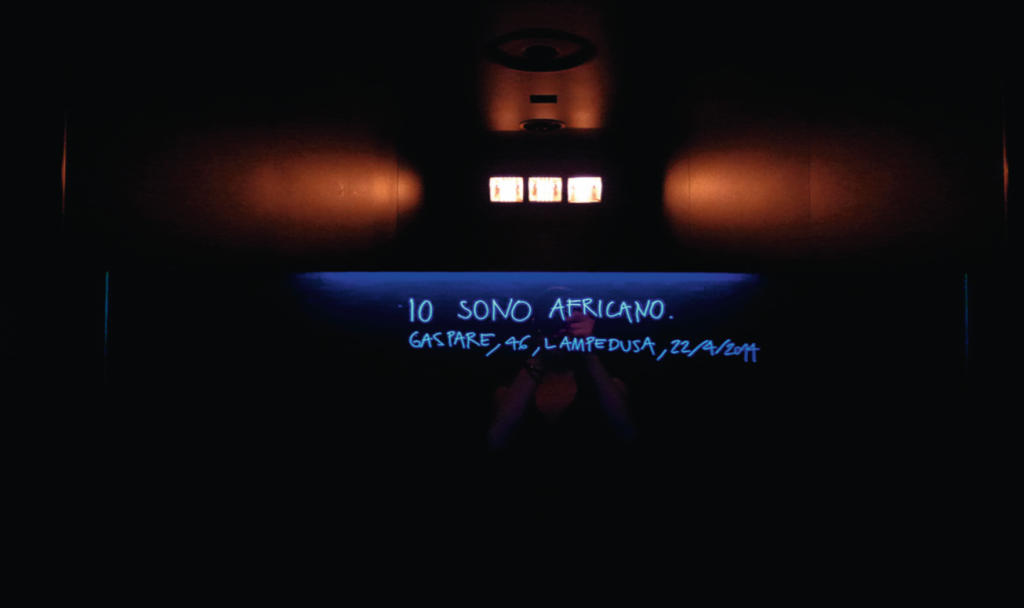

Back in 2014, Intermundia research project questioned the alternating border-scapes of trans-European and intra-European migration. The focus was put on the Ital- ian island of Lampedusa, a metonymy for contemporary Western conditions of con- finement. For me, back then it was clear that the dominant discourses on illegal migration obscured the role of international migration as a regulatory labour market tool. It was important to stress that migrants must be conceived primarily as workers, not only as immigrants. It seemed that, in the pre-pan- demic times of constant mobility, involuntary territorial shifts of the precarious workers was in parallel to the detention of undesired migrants. Instead of observing Lampedusa as a con- solidated institution of a waiting room, as a jailed zone in the middle of a conflict, Inter- mundia attempted a post-human perspec- tive in order to investigate the ambivalent state of in-betweenness. I was aware of the impossibility of the cultural translation of such a condition, the understanding of the Other, so the project Intermundia, exhibited and awarded at the Architecture Biennial in Venice 2014, challenged visitors to immerse themselves into a coffin-like light and sound installation. Inducing Verfremdungseffekt, the project asked for solemnity and re- action, and not simply empathy. I am not sure Intermundia actually opened up the important topic of migration in Europe, but for sure it was a predecessor to the summer of migration in 2015, with its great influx of migrants, refugees and the formation of the so-called Balkan Route.

What does architecture mean to you?

I dare to say that the fundamental task archi- tecture has is to articulate spatial thinking, thinking capable of asking questions about the burning issues of our society in a differ- ent way, hence of also creating a different reality. Architecture must offer a space for understanding the existential conditions of an individual and of society, and must also construct a foundation for a life with dignity. We know who we are, and where we belong, precisely through human constructions, both material and intellectual.

Intermundia at the Venice Biennial in 2014. Foto: © Ana Opalić

Intermundia “Io sono Africanicano”. Photo: © Ana Dana Beroš

MIGRANCY: The Psychogeographies of the Threshold, 101 (2017) issue od Život umjetnosti magazine, edited by Ana Dana Beroš. Cover photo: Geotrauma. Photo: © Matija Kralj Štefanić, cover design: Bilić_Müller Design Studio

Written by: Boštjan Bugarič

Photographs: Matija Kralj Štefanić, Ana Dana Beroš, Marin Nižić, Ana Opalić