Interview with Irfan Hošić, the founder of KRAK

Centar KRAK (Klub RAdnika Kombiteksa – Kombiteks’ workers club, the KRAK Center for Contemporary Culture) – located in the city of Bihać, in the far northwest of Bosnia and Herzegovina – quickly distinguished itself as one of the most active cultural organisations in the entire country. KRAK was founded by the Revizor foundation, notable for organising several architectural competitions in a country where these are very rare. The home of the centre is a reconstructed worker’s club building of a large socialist textile factory. According to its founder, Irfan Hošić, a professor at the local university and one of key members of Revizor, its existence is the fruit of a decades long project that included various endeavours directed towards contemplating, researching and revitalising the socialist past and its industrial heritage.

The entire region of Krajina, of which the city of Bihać is the centre, is a beautiful, fertile, and mild landscape that is, as it name suggests – as krajina can mean “edge” – a peripheral, liminal place. The proximity to the EU has always been an advantage and a curse at the same time. Local industry collapsed after the war, leaving the region impoverished, and thus is it has been plagued by the emigration of the locals towards the West and tensions towards migrants from the East who try to cross the nearby border.

In that kind of social and political climate the centre serves as a gathering spot for a small but growing community of like-minded individuals. The activity of the centre is characterised by a thoughtful, extremely serious approach to the organisation of events, and it is clear that every detail matters to the team. The number of events organised in the centre in a space of just a few years is impressive. There are exhibitions, concerts, artist talks, poetry readings, workshops, cooking classes and many more. A great deal of these are related to industrial heritage, spatial policies, and urban problems. The titles of some of the events are good illustrations of the themes.

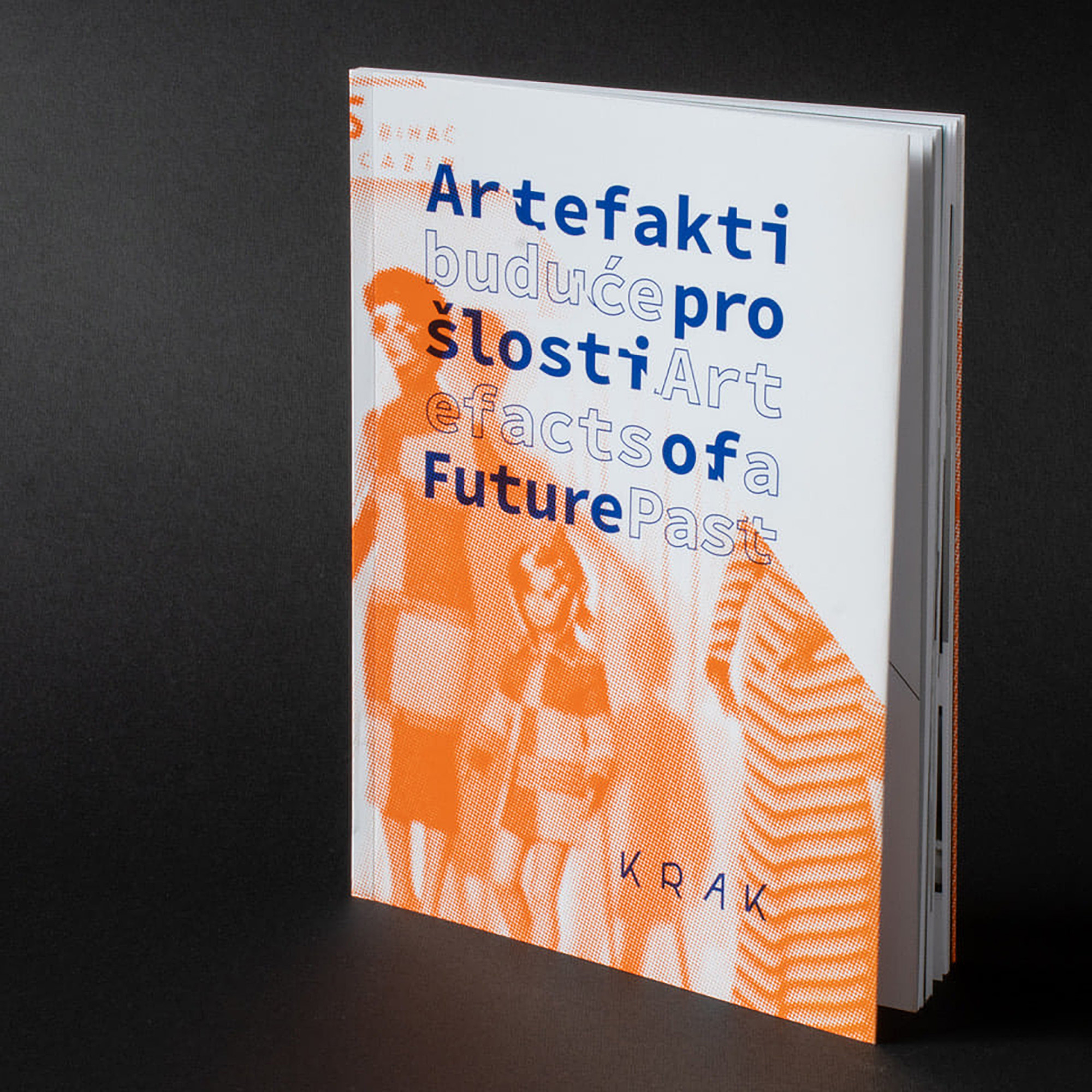

For example: Our Spaces, Curating the Periphery, Everyone Wants a View, Artifacts of a Future Past, Geographies of Belonging and the list goes on and on. I was interested in learning more about KRAK, and Irfan was kind enough to answer a few of my questions.

How, when and where did KRAK appear, was it premeditated or spontaneous?

KRAK has its genesis, and was not something that came into being overnight. Because I work at the university – at the Department of Textile Design – my activities as a teacher were in a way a part of that genesis. The department was founded more than 50 years ago, in order to serve the large textile industry in the city. I dealt with the question of industrial heritage in both theoretical and practical ways. In particular, I concerned myself with the question of our relationship with that heritage, after all the things that happened in the ‘90s, the war and the transition to a liberal economy that destroyed most of the textile companies. So, a lot of things happened along the way, scientific, custodial matters, exhibitions and so on, that somehow lead to KRAK being formed.

A lot of people also participated in that process. They gave their input on what it should look like, but in the end it all came down to me to actually make everything happen, as a kind of administrator of the whole process. There is a manifesto on our website that summarises the idea of KRAK.

The manifesto is a catalogue for the exhibition “Artifacts of a Future Past”. Unfortunately, there is no space to print all of it here. So a brief summary would be that the idea behind KRAK was the revitalisation of socialist industrial heritage, but also using that theme as a starting point for questioning the values of the former socialist system, and the current capitalist one.

So the location of KRAK being in the industrial complex of Kombiteks was always one of the conceptual goals of that idea?

To tell you the truth, not really. In 2017, during one of my courses called “Design and Crisis”, which incorporated an architectural competition, if you can remember – the competition for the revitalisation of the water tower.

Public Discussion: Curating the Periphery. Irfan Hošić in conversation with Zdenka Badovinac, Molly Haslund and Šejla Kamerić, 2023.

Of course I remember. I wanted to participate, but because various things in life happened, I wasn’t able to.

You see, that was our initial idea for Kombiteks. We daydreamed about that water tower. Its history, typology, its spatial dynamics called us to imagine, to speculate what it could be in the future. The space we are now in wasn’t in our focus at the time. Then, completely by chance this building was offered to us, because we organised an exhibition there called “Artifacts of the Future Past”. At the time it was, of course, a ruin. We wanted to make an exhibition in the ruin. The mayor visited us and found our work interesting. He offered it to us because the city inherited the space but didn’t have an idea what to do with it. At first, I declined. The space was large and completely destroyed. It would take a lot of funds to actually make it operational. Then the mayor said: “It will wait for you if you ever change your mind.”

A year passed, then some people called to tell me that they had a fairly large sum of money at their disposal and wanted me to propose “something big”. It was really a lot of money. So that first idea which the mayor had put into my ear awakened, and we shifted our focus from the water tower to the KRAK Center.

After that we called two young architects, Ena Kukić and Dinko Jelečević, that we spotted during our competitions to help us design the centre. They agreed to work pro bono, approached the project extremely seriously, and did a fantastic job.

So in the end we had a great design, we had the funds and the support of local government. The construction process was demanding, a lot of money was spent, but we succeeded, and now the centre lives its own life.

Was local community involved in the construction? Usually, people come to help with such projects so the construction of a centre like this also serves as a way of building the community.

Unfortunately, the construction process happened during the COVID pandemic. So in that sense we were not able to organise people to come and help. Additionally, I was living in the USA for a year, so I was not personally able to facilitate that kind of interaction. It would be great if it had happened, but a local community in that sense did not even exist then, it only started to grow once we opened the centre. It’s a hard, laborious process. It’s difficult to animate people. You know, even in a nuclear family of four the division of labour is not equal. Oftentimes, one person pulls majority of the weight. But fortunately I am proud to say that now we have a community and it’s still growing. One great example was an art project, a sculpture by the Berlin-based artist Alban Muja. It involved the nearby tower block called “Solidarnost”, which was itself a remnant of textile industry – it housed Kombiteks workers and their families. Muja envisioned the installation of a large inscription that read “Svi Žele Pogled” (Everyone Wants a View) on the top of the block. The entire community living in the block became involved. But the process started with difficulties. Initially the residents were extremely suspicious. When I first entered the building they saw me as some kind of investor who wanted to take away something from them. Gradually they opened up to the project, and we became close to the point where I was regularly invited for lunch. Now they are very proud of their tower block and the artwork.

Symposium: Our Spaces, organised by KRAK, December 8, 2023.

KRAK building: Ground floor; Ena Kukić and Dinko Jelečević; E + D.

KRAK building: Visualisation of the interior; Ena Kukić and Dinko Jelečević; E + D.

We also had another project, a multi-disciplinary effort. It involved a lot of outside stakeholders – the Association of Architects of BiH, and the faculties of architecture in Sarajevo and Banja Luka. The theme of the projects was Hatinac, the neighbourhood where KRAK is situated. We tried to conceptualise the neighbourhood, how it can be revitalised and improved. That was a process-oriented project.

The manifesto of KRAK.

Alban Muja - Svi Žele Pogled, captured from a video by Alban Muja. The video documents artist’s stay at KRAK Center, 2022.

Yes, that was my next question actually. How did KRAK influence its surroundings? Spatially, but also culturally? Is there a change in perception of that area by the local population? I imagine that before KRAK it was a dilapidated former industrial zone. Now there’s something active, something alive but very different in that area. How did that work out?

Yes, of course it has changed. We revitalised the building but also the space around it. Right now we are planning to expand to immediate surroundings of KRAK as a part of a project called “Curating the Periphery”. This is something that should happen this year. The architect Ahmed Ibrahimpašić developed a design for KRAK’s neighbourhood. The design he came up with is very ambitious, so some parts of that project are, for now, unattainable for us. But it has been very inspiring and has driven us to interpret it in our own way to make it feasible.

It is like a concept design for a car, full of flashy things that never get manufactured exactly in that way, but becomes an inspiring template for the future.

So yes, we are satisfied with this process.

Our/Your border, project by Nermin Duraković, 2021.

Swings, installation by artist Molly Haslund in the city centre of Bihać, 2024.

With regard to the events in KRAK, and judging from the website and your social media channels, you’re very active. How much of that is planned in advance? Do you have a concept for a year, half a year?

It depends on the finances, of course, but also on the human resources available. We try to respect the people involved in KRAK as much as we can. Right now we have about 20 upcoming events announced, with last one being in September. For us this is a great success, although with large amount of work behind it.

In my experience, having dabbled with the organisation of some events myself in the past, that’s quite a serious schedule.

Well, we’ve succeeded in making the announcements, now we’ll see whether we succeed in the realisation. But the announcements are also tough, and we put a lot of work into them. Every event is announced with a page and a half of text, everything is contextualised, explained, translated into English, and accompanied by photographs. It is a publishing project that takes a lot of time and resources.

What about finances? Besides projects and donations is there a plan for some kind of sustainability?

Not really. Maybe if seen from some other perspective, then yes. Let’s say that KRAK has seven active members. Most of them come to KRAK, work there for themselves – such as graphic design, sound design, videography, and so on – but that’s not the answer to your question, that’s something that doesn’t concern KRAK’s program directly.

KRAK doesn’t have any kind of activity that would make it sustainable. It’s impossible to, for example, charge a fee for the tickets to the events here. But we are ok with that. Financial sustainability is forced upon art by capitalism. Everything must be profitable, everything must make money, and if something does not then it must be terminated.

The conversation with Aleksandar Hemon, held on 3 June 2023 in KRAK.

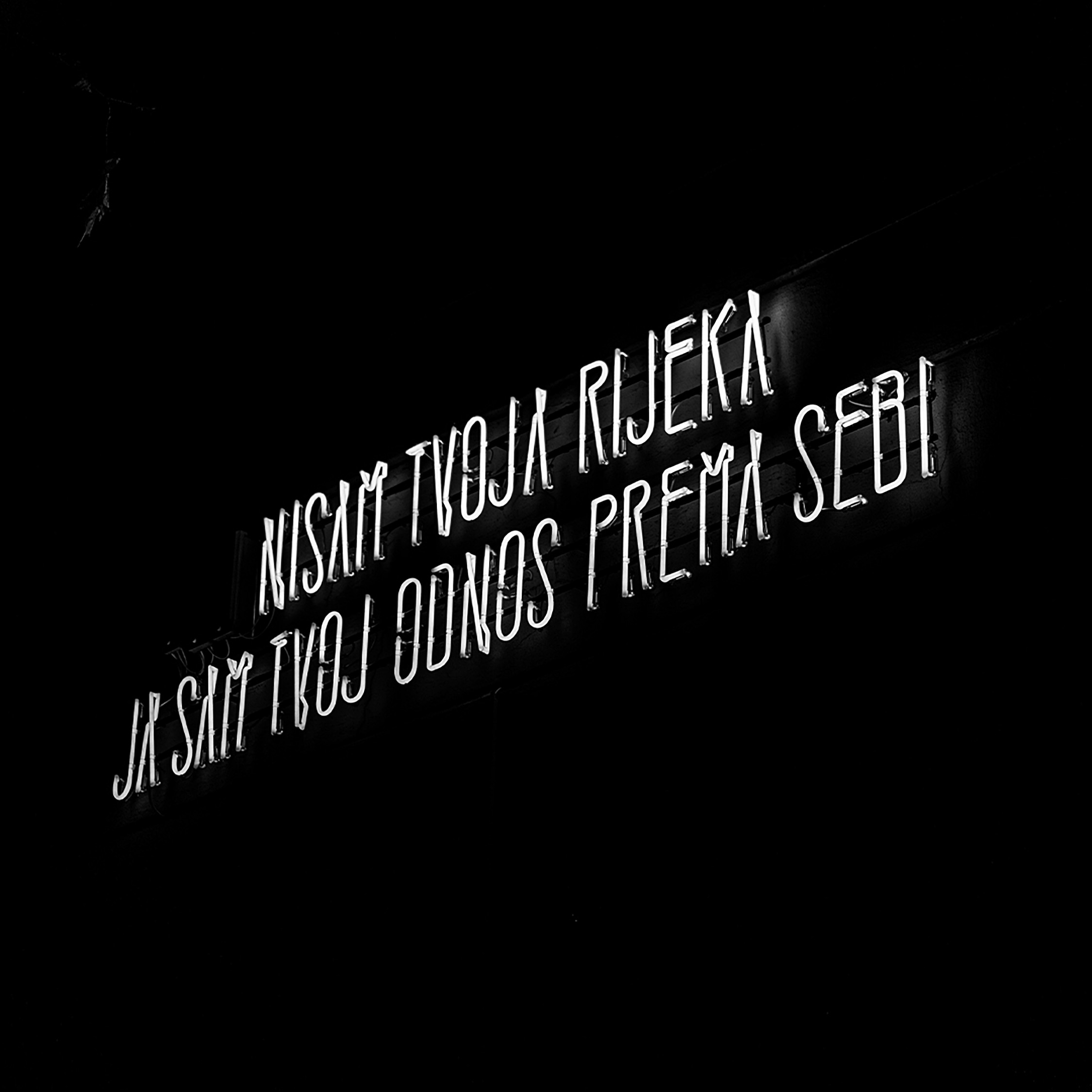

Urban Poetry: Nisam tvoja rijeka: I am not your river, I am your relationship towards yourself, Mehmed Mahmutović, poetry, Adnan Suljkanović, Graphic design, 2022. KRAK installed this art work on the facade of a local library.

I don’t agree with that. Art isn’t profitable, the humanities aren’t profitable. Culture isn’t profitable if it’s not commercialised. These are things that society needs, and society should set aside some resources for them. Of course, in more developed societies people can afford to buy tickets so this kind of sustainability can be achieved. Here in Bosnia, where a lot of people can barely scrape a living, that kind of sustainability isn’t possible. And this is true not only in Bihać, but also in larger cities like Sarajevo. It’s very difficult, so we don’t plan the future of KRAK with the goal of financial sustainability. We’re just not interested in that.

Now you just mentioned Sarajevo, do you have collaborations with similar initiatives from other cities?

Yes. There’s Manifesto! The most intensive collaboration is with the Manifesto gallery in Sarajevo, to the extent that I’d say we are siblings. We help each other a lot, financially, conceptually, and so on. We are like brothers and sisters. We are also trying to develop a similar connection with Vagon Gallery in Banja Luka and it’s going very well, they will curate an exhibition for us, which is for our 2024 “Zvono” award. We’re trying to connect with people in every direction.

That’s great, because as I investigated organisations for the purpose of these articles a lot of them seemed isolated. They reached their potential, the potential of that place where they came from, and then what? A lot of them lost strength and ceased to exist because there was no external drive. I also think that building these connections is extremely important, especially for smaller communities. In those communities I also include Sarajevo, which is a hard periphery in some larger terms.

Now when you’re talking about this, I’ll also have to mention our fanzine. We already have five issues. The idea is to map Bosnian-Herzegovinian cultural initiatives, similar to KRAK and present them in the fanzine. Our younger colleague artist, Adna Muslija works a lot on that.

The last question is how do you see art and activism in times like today, when it seems that everything is becoming darker, day by day, that we are in desperate need of art – true art – but the art is marginalised? Artists are not heard in the media, their standing in society, their influence is limited. For example, when you look at how great artists were respected in the past, now we seem to be very far from it. Today, especially in poor societies like Bosnia, working in art means poverty.

Well, we do what we do, and that act is a political act. In the spaces we occupy – physical and virtual – we act, we encourage some values, some ideas. Because of that we believe that some kind of change is possible. We continue to work with a belief that our ideas are important and have the potential to change the world. Let’s say it like that.

KRAK Center for Contemporary Culture, Dom USAOJ, Bihać. The KRAK team members are: Irfan Hošić, Artistic Director, Mehmed Mahmutović, Creative, Sead Okić, Photographer and Videographer, Adnan Suljkanović, Graphic Designer, Jasna Pašić, Historian, Sijana Hošić, Architect, Mirza Šišić, Sound Engineer

Text: Dario Kristić

Photographs: KRAK archive