I like to keep things simple, which is perhaps the most complicated thing one can do in this world today

I met Ken right at the beginning of the millennium, when I was invited to his small, very international but charming architectural symposium in Canova. There I was greeted by a few surprises: firstly, the extraordinary cultural landscape of the Ossola Valley, hidden somewhere between the peaks on the border with Switzerland to the north and the salubrious influences of Lago Maggiore to the south, dotted with a built heritage of stone architecture that was largely abandoned or in disrepair.

Ken and his wife Kali, after several stopovers, came from the US to the hamlet of Canova, where together with their daughters they decided to make their home. Having been invited to participate in the annual Canova International Architect Encounter, it was in this small, extremely picturesque and comprehensively renovated village, inhabited by a variety of interesting people, that we found ourselves in the midst of equally interesting brainstorm-ing sessions to admire the renovation skills and the habitability of traditional vernacular construction. Twenty years have now passed – we have revisited the Encounter twice in the meantime – and many remarkable personalities have presented their work, from the traditional to the very contemporary, in the years since. Now Ken is handing over the mission of saving the valley to the younger generation, who are now moving to the villages. The Canova Association which this month has evolved into The Canova Foundation, has raised awareness of the importance of the indigenous stone heritage in the valley, and has helped save many houses and hamlets, while at the same time becoming an institution that organises summer schools in stone construction for students from Italian and foreign architectural faculties. This year the Canova Foundation will celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Canova International Architect Encounter.

What attracted you to the field of architecture?

My father was a master cabinetmaker and was always building or renovating something, including the wooden house we built when we returned to the US after spending five years in Europe. The fine cedar siding rather elegantly hid the fact that it was a lightweight box. Not even one year had passed before the front door didn’t close properly. I longed for the medieval stone houses we had lived in over the previous years in Ireland, Greece, and Spain.

Can you tell us something about your and Kali’s life that has shaped you in a particular way, and influenced your work?

Already at 12 years old my bedroom walls were plastered with photos of the Alps cut out from National Geographic, and I had already prepared my parents for the day when I would leave home and move to Europe. It was a combination of two things I think. One was that my parents shared a secret language when they didn’t want their eight children to understand. Despite my insistence on knowing the story, they didn’t seem to be able to explain this to me. Only years later did I discover the tragic story of their past as German refugees from Ukraine. My maternal grandmother never learned English.

Kali and I met when we were 17 years old, and she shared the same wanderlust, dreaming of living in Ireland, the land of her ancestors. We were 22 years old when we began working in Ireland’s only health food store down on the Liffey in Dublin, and did a thriving business. After a year and a half in Ireland we started walking from the most western point on the Dingle Peninsula and ended up on the Island of Kefalonia in Greece a year and a half later. We slept under the stars and never took public transport, a journey of about 2,000 km. Our first child was born in the 16th-century Venetian lighthouse in Fiskardo which had become our home. Two years later our second daughter was born in an 18th-century stone finca on the island of Menorca. By that time the classic American wooden house with an average lifespan of 30 years had been replaced by a passion for stone. Perhaps obsession would be a better word.

How important is the relationship between the physical, cultural, and spiritual context in which you were raised in the US, and the one you have been living in for the majority of your life in Europe?

I think it was the superficiality of a culture of consumerism that I just couldn’t handle in the US, something that the residential architecture reflects. After living in medieval stone houses in Europe I discovered what it was that I’d always needed. I love being one more guy who is just passing through, so to speak. How many people have been born and died within these walls? I felt great relief to see myself not so much as an owner, but rather as a caretaker.

How did things start in Canova?

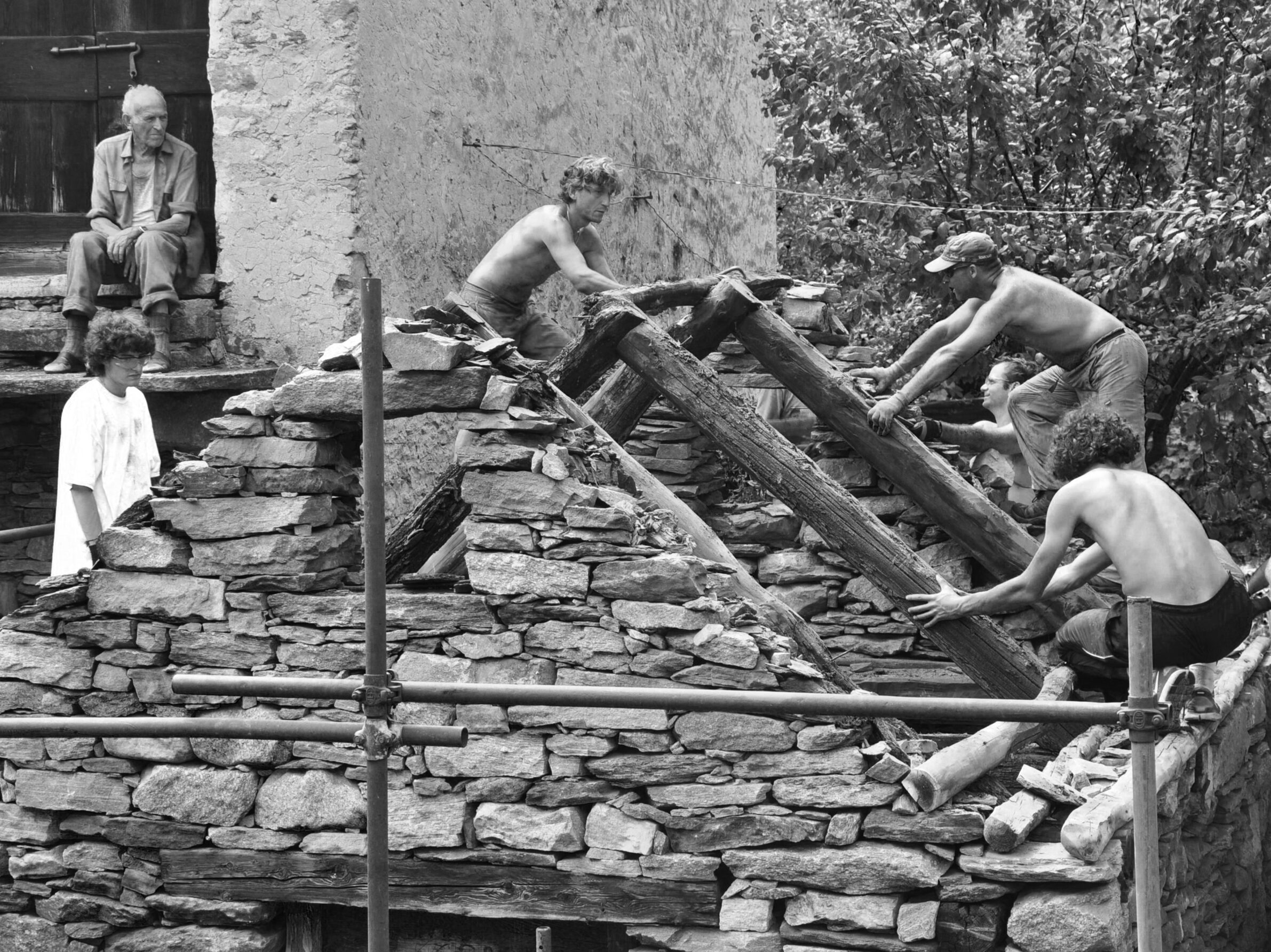

When we moved to the village of Canova in 1989 it was mostly in ruins. We bought one of the few houses with an intact granite roof and I began restoration. I had the great fortune of meeting a highly skilled young Calabrese muratore, or stonemason, who had begun as an apprentice at seven years old. I had now become his. We actually learned a lot from each other, since he insisted that all walls must become perfectly straight and plastered with Portland cement. If he hadn’t been the most peaceful man I’ve ever met we might have come to blows, as I insisted we would leave the crooked walls and use only lime plaster. Since I founded the Canova Association in 2001 my goal has been to do what I can to offer a similar learning experience for aspiring architects, young and old.

What are you most deeply involved with at the moment?

At the moment I am dedicating long days restoring a small house we purchased 5 years ago. The renovation projects that attract me the most are the ones in a disastrous state but with great potential. The current project puts most of the past projects to shame in that regard. Truckloads of garbage need to be moved, and illegally built outhouses must be demolished. The transformation is going to be dramatic and every day I can’t wait to wake up in the morning and go at it.

My role in the Canova Foundation has changed recently when I passed on the presidency to Maurizio Cesprini. I’m still active in the organisation of our international field schools and the general planning of events. My main project is the annual Canova International Architect Encounter that will celebrate 20 years this June, with 25 out of the 65 previously participating architects confirmed to join us in late June.

What is the relationship between research and analysis and the creative part of the design, between theory and practice?

Well, in my own personal approach to the restoration of a house, research and analysis are minimal. I know it sounds silly, but it is the house itself that tells me what to do. The process of cleaning and uncovering layers leads to discoveries that more often than not radically change any preliminary plans I, or an architect, might have in mind.

In the case of the Canova Foundation, however, research and analysis play a significant role and we work closely with several Italian universities and private specialists with regard to testing processes for documenting heat retention, humidity levels, and various insulating factors that are particular to a house built entirely of stone.

How would you briefly define your human and professional philosophy or outlook on life?

I like to keep things simple. That’s perhaps the most complicated thing one can do in this world today. As involved as I am in the revitalisation of our medieval rural stone heritage I wouldn’t mind living for a time in the Farnsworth House.

My credo might be described as “Why do something just because you can?” Respect for what exists coupled with a good dose of humility could do a lot to diminish the culture of consumerism and make for more sustainable habitation.

What is your advice to young people entering the field of architecture in these complex times of various crisis?

Get your hands dirty. And study, but don’t think too much.

The Village of Canova, 2007. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Village of Canova in 1990. Photo: Ken Marquardt

One of many guided visits open to the public organised by the Canova Association, 2007. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Carla House, Canova 2006. Photo: Ken Marquardt

The Carla House, Canova 2008 before being renovated and becoming the office of the Canova Association. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Carla House, Canova 1990. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Interior of “la Torre”, Canova 2012.Photo: Ken Marquardt

“La Torre”, Canova 2008. Photo: Ken Marquardt

The “Long House” in Ghesc. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Casa Alfio, Ghesc, under renovation, 2007. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini

Maurizio Cesprini working with field school students, 2011 Photo: Ken Marquardt

Field School with University of Oregon, 2012, Croppo Marcio. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Canova Foundation house, Casa dell‘affresco, Ghesc. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Building a vault with Yestermorrow school from Vermont. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini

Ruins of Ghesc in 2013. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini

Casa Alfio after renovation. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini

Casa Alfio after renovation. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini

Field School, State University of Milan, 2022. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini

Worksite in Ghesc 2023. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini

Canova Foundation musical event in Ghesc. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini

Village of Ghesc April 2024. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Canova Foundation musical event in Ghesc. Photo: Maurizio Cesprini Village of Ghesc April 2024. Photo: Ken Marquardt

Text: Aleksander Ostan

Photographs: Ken Marquardt, Maurizio Cesprini