Mitigating the danger of floods

Venice is a city built on water. After the dissolution of the Roman Empire, the inhabitants of the region fled from barbarian hordes and found refuge on small, low lying islands, just off the coast, surrounded by a large saltmarsh. The settlers found ways of building on the unstable ground by pushing strong wooden pillars into the mud, which then served as their buildings’ foundations. Through the ingenuity and industry of Venetians, the city-state became a naval superpower and financial centre, controlling most of the Mediterranean trade over the centuries. What we see today is the legacy of the city’ rich cultural, artistic and architectural tradition.

Bocca di Porto di Lido, the entrance to the Venetian lagoon. Photo: Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - Archivio Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22785956

Yet the constant threat of being flooded and submerged persisted. While the Adriatic Sea has a relatively low tidal range of about 40 cm, specific weather conditions can trigger an increase in water levels. The shallowness of the Venetian lagoon – mostly under 1m – exacerbates the impact of the winds and other events on the height of the tide. When the sirocco wind from the southeast blows it pushes the tide higher than usual, sometimes much higher, causing the acqua alta (high water), and flooding large parts of Venice.

Traditionally Venetians have found ways of coping with the specific environment of the lagoon by developing creative solutions to the constant threat of already partial submersion. Two of the rivers flowing into the lagoon, the Brenta and Sile, were diverted some 400 years ago in order to decrease alluvial deposits to the lagoon. The lower parts of the Venetian buildings are clad in non-porous white stone, imported from Istria, that resists salt water exposure, while the upper parts are made of much lighter yet porous brick. The lowest floors of the buildings typically serve as storage space, or even as water “garages” or interior ports for mooring boats rather than residential use. Seawalls were built on the outer islands in the 18th century, although they later crumbled under the force of storms. In case of flooding the city deploys raised platforms on the most frequented walkways, and there are two versions of these – one about 15 cm high and the other about 45 cm high. The most exposed buildings also have systems of glass flood barriers that protect the entrances. The city gives rather dry and brief advice about impacts of high water in certain parts of Venice and its impact on public transport, and until recent years this has been mostly enough when floods arrive.

Flooding of the San Marco area. Photo: grumpylumixuser, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58817492

However, the combined effects of the sinking of the city by about 1 to 2 mm per year, the rising of the sea level and increasingly frequent and violent weather events mean that what used to be just a nuisance has become catastrophic. Since 1966 there have been almost 300 tides higher than 110 cm, compared to just 47 such tides in the 50 years before that, from 1916 to 1966.

Following the highest recorded tide of 1.94 cm, which flooded almost the entire city in 1966, the Save Venice movement emerged. This led to the formation of Consortio Venezia Nuova, a private consortium that designed and built the MOSE project (Modulo sperimentale electromechanicco, or the Experimental Electromechanical Module) in the early 1980s. The project faced many delays, often amidst allegations of corruption and other scandals. Finally, on 3 October 2020 the gates of the MOSE project protected Venice for the first time. The final cost of the project was approximately €7 billion.

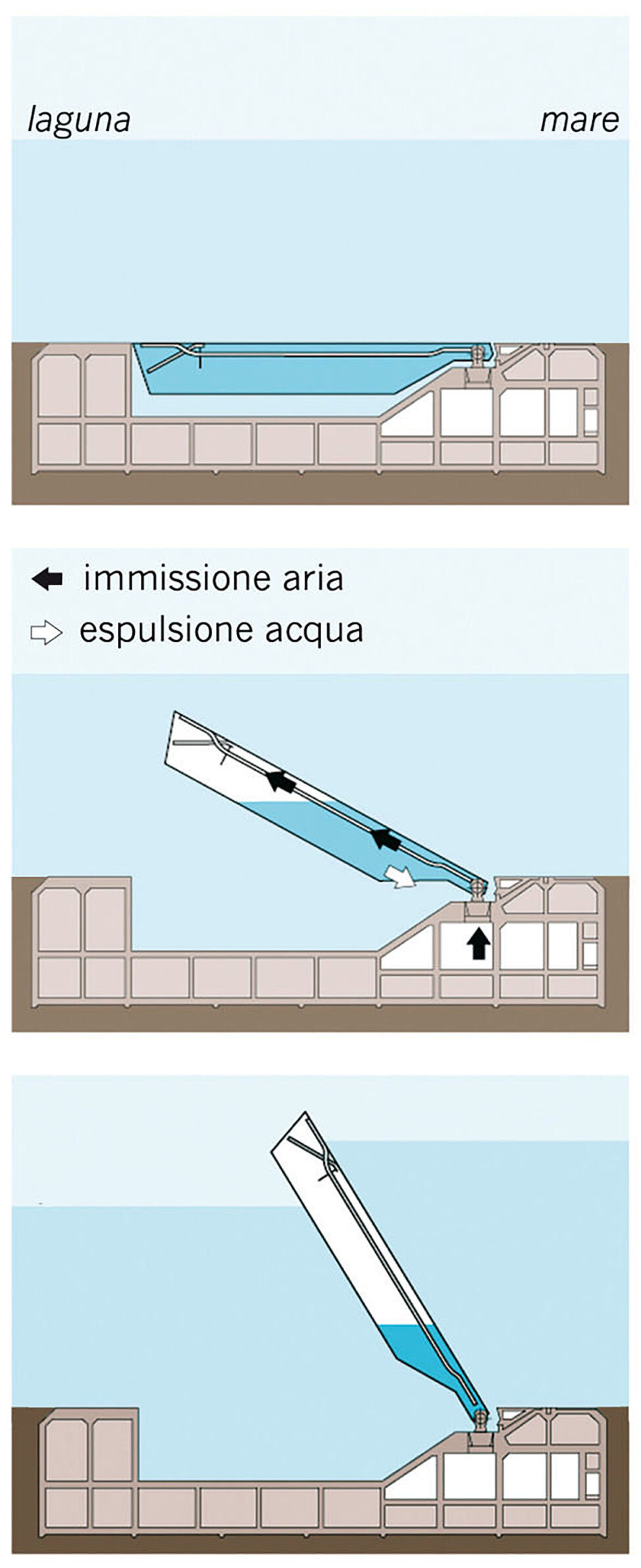

The MOSE system operates on a simple principle: to prevent excessively high tides from entering the lagoon when necessary, while remaining hidden from view during normal conditions. Crucially, the barriers must seamlessly integrate with the environment, disappearing when not in use and avoiding any disruption or harm to the lagoon’s delicate ecosystem.

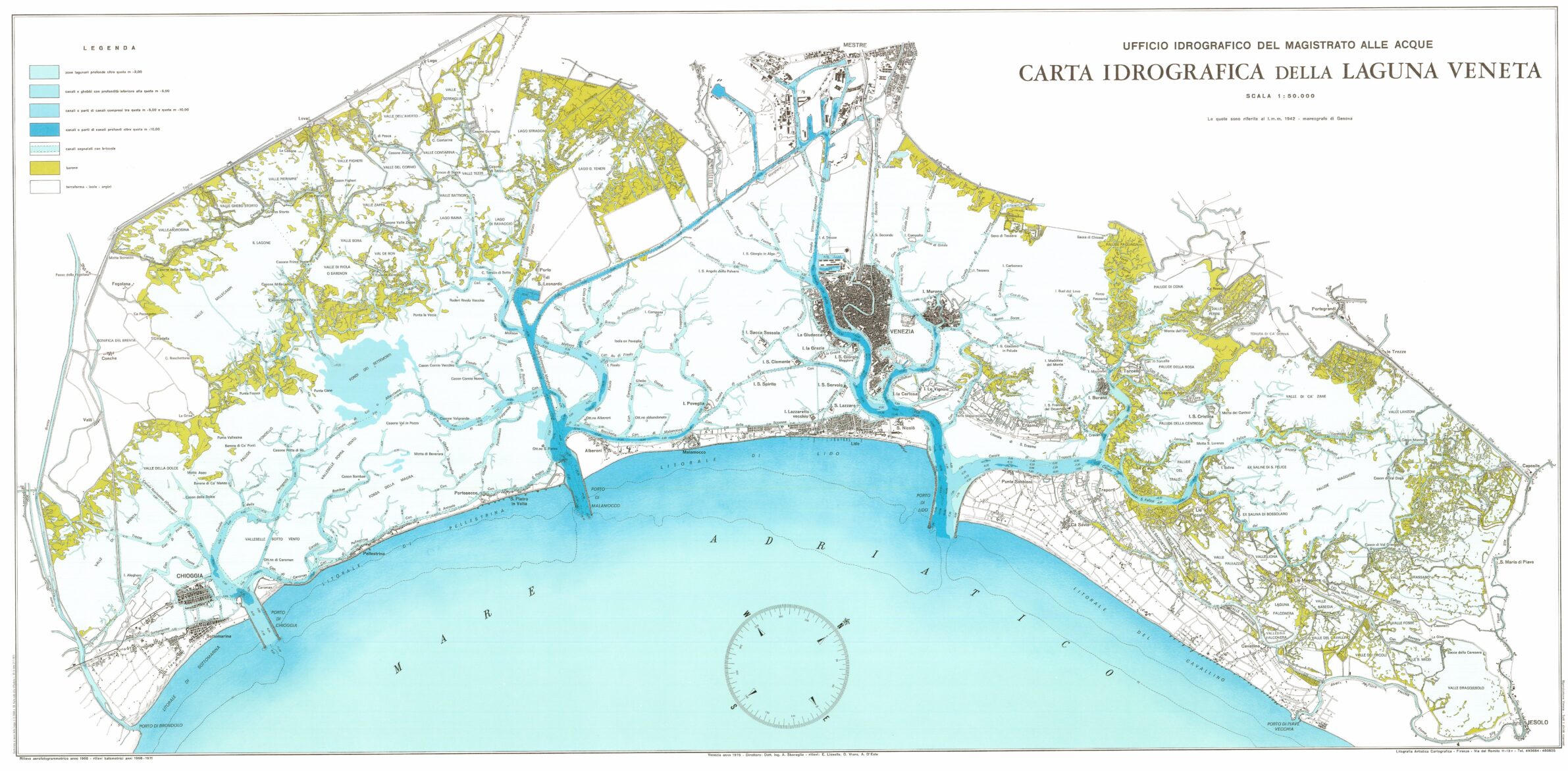

In order to prevent excess water from entering the lagoon, all of the three entrances – Bocca di Chioggia, Bocca do Malamocco and Bocca di Lido – have a system of self-deploying barriers, made up of a total of 78 metal gates, or paratoie. When not in use the gates remain submerged in the water and lie flat on the ocean floor inside the foundations. The foundations of the gates are made of concrete and are equipped with a service tunnel. If the tide surpasses a certain level compressed air is introduced into the metal boxes, expelling the water and raising the barriers, fixed on hinges, in order to close off the flow of the seawater. It takes less than 30 minutes for the system to deploy. The decision to close the gates must come about three hours before this, based on several meteorological factors. The weather conditions are monitored from the Acqua Alta Oceanographic Tower, installed about 15 km off the coast of Venice in 1970. The MOSE project’s operations centre, located within the Arsenale complex, manages the activation and deactivation of the gates.

Schematic of functioning of the MOSE system. Photo: Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24448791

It is necessary to maintain the gates in good working order, thus each gate is replaced every 5 years. A specialized vessel “Jack up” is designed for installing and replacing the sea gates. Additionally, routine cleaning is required to maintain the gates clean and free of sand and algae deposits.

Despite its ingenuity, the MOSE project has not been without controversy. The expense of operating and maintaining the system – which costs over €300,000 each time the gates are raised – is a significant concern. An additional concern is that the gates are only partially effective, as the Piazza San Marco, which is the lowest point of the city, is still subject to flooding. This is because the San Marco area floods at tide levels of approximately 80 cm, but the gate only rises at levels exceeding 110 cm. Furthermore, when the gates are raised they stop all water traffic to and from the lagoon. This obviously causes certain problems, especially considering the worst case scenario predictions, which project more than 180 days per year of tides exceeding the 110 cm threshold by the end of the century. Environmental concerns also surround the MOSE system, as closing the gates for even brief periods of time disrupts the natural circulation of the lagoon water, thus harming sensitive saltwater marsh ecosystems.

The three locations of the MOSE gates. Photo: Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24448018

While alternative solutions have been proposed – from injecting water into the sandy layers under the city, which some claim could raise it by about 30 cm, to building a super levee around the lagoon – MOSE currently serves as a crucial and for now the only solution for safeguarding Venice.

Schematic of functioning of the MOSE system. Photo: Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia - Consorzio Venezia Nuova - http://www.salve.it/wiki/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24448791

Jack-up, the maintenance barge. Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=63335651

The MOSE project offices in Arsenale. Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24670225

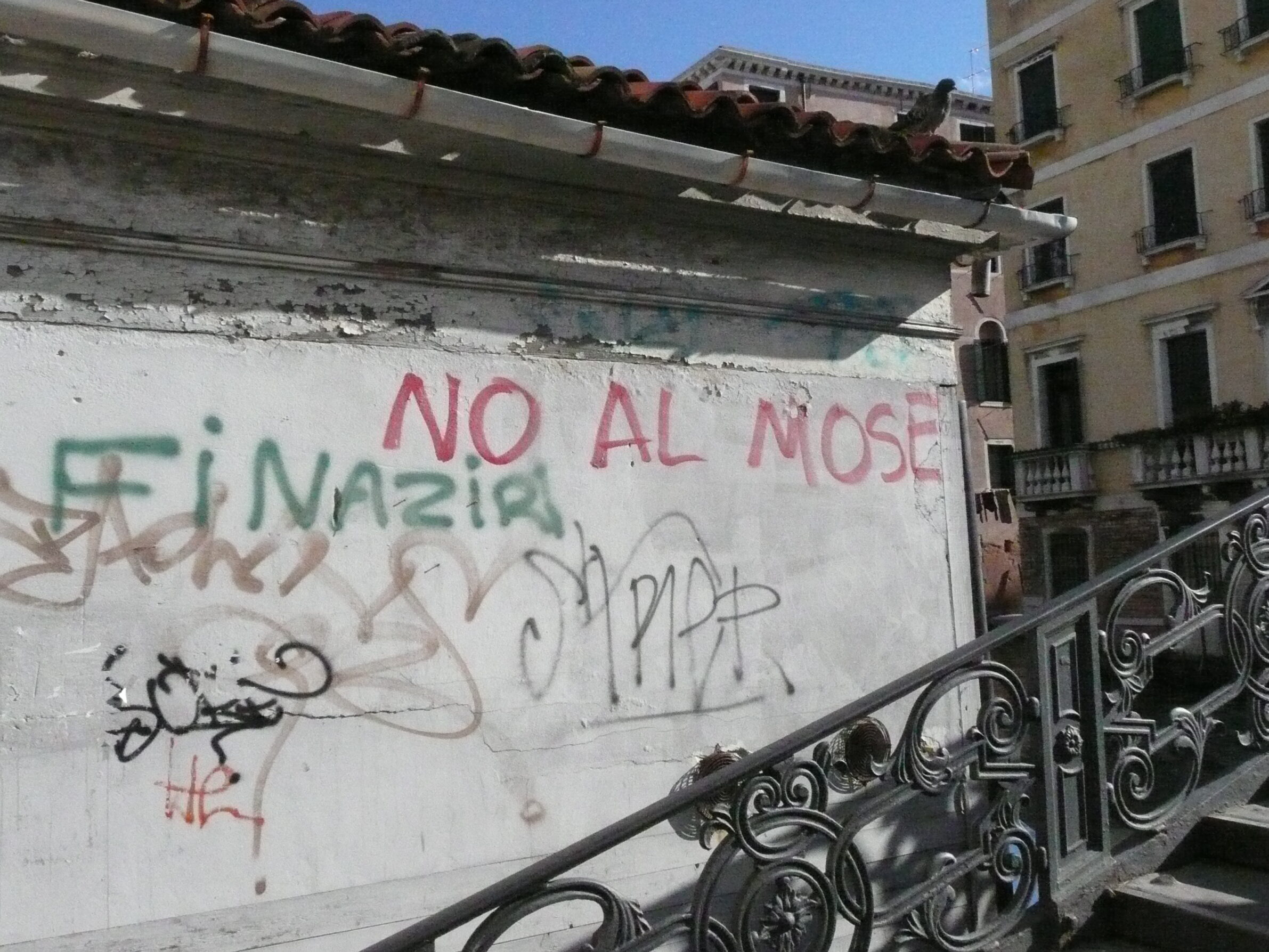

Some inhabitants and environmentalists oppose the MOSE project. Photo: Nau Kofi - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3949289

The meteorological tower off the coast of Venice - the ISMAR - CNR platform. Photo: Comune di Venezia - https://www.comune.venezia.it/es/node/5703, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74234093

References:

Commune di Venezia, https://www.comune.venezia.it/en/content/venice-and-high-water, last access: 24 April 2024

ISMAR-CNR https://www.ismar.cnr.it/en/infrastructures/oceanographic-infrastructures/acqua-alta-tower/, last access: 24 April 2024

Lionello, P., Nicholls, R.J., Umgiesser, G., and Zanchettin, D.: Venice flooding and sea level: past evolution, present issues, and future projections (introduction to the special issue), Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 2633–2641, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-21-2633-2021, 2021.

Mel, R.A. Viero, D. P., Carniello, L., Defina, A., D’Alpaos,L.: The first operations of Mo.S.E. system to prevent the flooding of Venice: Insights on the hydrodynamics of a regulated lagoon, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, Volume 261, 2021,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2021.107547.

MOSE https://www.mosevenezia.eu/mose/?lang=en, last access: 24th April 2024

Scientific American (2019, November 4) Venice Has Its Worst Flood in 53 Years, https://www.scientificamerican.com/blog/eye-of-the-storm/venice-has-its-worst-flood-in-53-years/, last access: 24 April 2024

Hydrographic map of the Venetian lagoon in 1975. Water of a depth of less than two metres is coloured white. Salt marshes are yellow. Photo: Ufficio idrografico del Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59249692

Text: Kristina Dešman

Photographs: Vincenzo Chilone, grumpylumixuser, Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia, Fusi Sandro, Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, Comune di Venezia, Nau Kofi, Ufficio idrografico del Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia