The only certain thing is that we are in a transition period

Jure Miklavc started his career as a freelance designer, before founding his own design consultancy. Studio Miklavc works in the fields of product design, visual communications and brand development for clients in industries such as light design, electronic goods, user interfaces, transport design and medical equipment. Sports equipment designed by the studio enjoys worldwide recognition, and from 2013 the team has been working for the prestigious Italian motorbike manufacturer Bimota. Studio Miklavc has won many international awards for its work, and been included in numerous exhibitions.

Since 2005 Jure Miklavc has also been involved in design education, and is currently the head of the industrial design department at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana. For more than a decade he has been a member of the Red Dot Product Design jury in Essen, the Red Dot Concept Design jury in Singapore, and the Contemporary Design Award jury in Xiamen, China.

The key point of GEM in-wheel drives is that there is an engine inside every wheel, right?

Exactly. The idea was to eliminate the losses that occur when power is transmitted from the source to – usually – some axle and eventually to the wheels. Once you can do that, there are several other benefits that emerge.

There’s no transmission here?

Yes, the engine rotates inside its casing. The most important added value of this engineering concept is that customers get the whole package and don’t need to do much else apart from inserting it into their products. It’s mostly used for vehicles operating at lower speeds, such as scooters and light delivery vehicles, as well as small people carriers like golf carts and similar.

The number of axles is not an issue in this design?

No, not at all. We need to keep in mind that whatever general solutions to mobility we adopt in the more or less near future, we’ll always have to address the problem of the last kilometre, just like now. Even with an ideal public transport system we still need to get from the station to our actual destination, and for decades several options have been tried, but none of them have proved acceptable for everyone.

Another product – and a service as well – where GEM solutions can be used is electric car-sharing. Mind you, this is for a specific car and a specific inner city, which needs to operate at lower speeds. GEM has a very clever package, even if it is not the whole product, and with this it follows a well-established pattern of specialist suppliers in the mobility industry. A globally successful Slovenian case in point is Akrapovič, which develops and manufactures world-class performance exhaust systems for many car and motorcycle firms.

GEM customers thus obtain batteries elsewhere, then use these together with GEM wheels and their own idea of a product and/or mobility service. Isn’t that similar to early cars, before industrial production?

Yes, this is a principle called coach-building – the very first cars were built exactly like horse-drawn coaches, they only needed to place the engine somewhere. Coach-building has never really disappeared in the ultra-luxury segment where, customers order extremely individualized cars. The interesting thing today is that digital approaches allow similar levels of individuality as artisans do, and so a customer may get a comparable level of exclusivity.

And this brings us to a real design task, because when individual components are being installed into vehicles they need to be recognisable in order to be desired, and they also need to be seen once they’ve been installed.

I believe we have achieved this goal with GEM – people who know their light electric vehicles, know the brand. What logically follows is that while developing the product design we were also developing the company’s identity. Obviously we did not start from scratch, but because this industry is so young we’ve had a remarkable opportunity to help shape not only the product, but also the corporate identity. And that made the design work both easier and more complex.

So GEM can be seen as a small part of the much larger green transition taking place around the world.

Yes, and I can easily see investors being interested in it, such as a municipality which wants to improve its last mile mobility service. Some cities offer bikes or scooters, Ljubljana even has chauffeured golf carts in the old city centre, and this is very close to what a GEM powered product or service could be a part of. It’s an exciting component – with electronic controls included – that allows for countless new creative uses.

If we can turn to a totally different project, you also work for a very high-end Italian motorcycle manufacturer, Bimota.

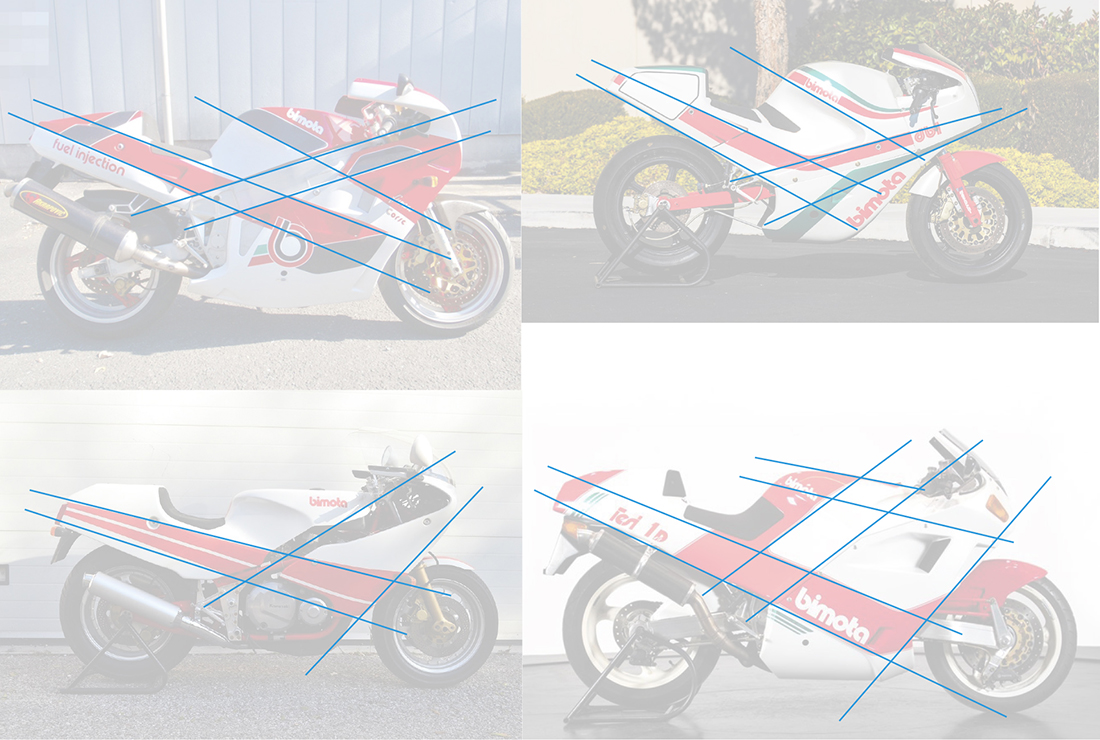

Actually it’s way beyond “very high-end”. At annual sales of only around 250 bikes, it’s probably the most exclusive such manufacturer in the world. In terms of the final outcome it’s quite a thin line between individually ordered and crafted pieces on one side, and Bimota bikes on the other, but these are still homologated vehicles, there is a Kawasaki-owned company behind it, there is a sales and service network, buyers are given the owner’s manual and so on. It’s ultra exclusive, though, in the highest possible price bracket and extremely limited editions.

But do Bimota – at this level of exclusivity – make any of the key components themselves?

Well, since their beginnings in the 1970s Bimota’s method was to take a mass-produced engine that met their very high standards, and then develop their own product around it. You should know that in motorcycles the most important thing is its geometry, defining the bike’s handling and other characteristics in motion.

In practice this means that more exclusive manufacturers can opt for more exclusive components. Mass production is always a compromise between price and performance, while at the more exclusive end of the market performance rules. This includes aesthetics, too, and involves components made to the precision grade of the best Swiss watchmakers.

And even these signature pieces are not made in house?

No, they’re made by the world’s best specialists, whoever that is for a particular component. Italy has clusters for most of its traditional industries, such as textiles, leather, furniture and so on, and the part of Emilia-Romagna from Modena and Bologna towards Rimini is known as la terra dei motori. Any petrol-head enthusiast knows it as the region where brands such as Ferrari and Lamborghini are based.

You mentioned “petrol”. Now high-performance bikes is supposedly one of the niche fields where electrification is not a serious option, although on the other hand mavericks like Rimac are outperforming traditional cars with electric-powered models.

I have less insight into cars, but in motorcycles some electrification has already occurred, and a lot more is certainly still to come. But this mostly applies to lighter bikes for urban transport or shorter commutes.

When we consider either longer distances or machines that need more power, motorcycles face bigger problems than cars due to the increased weight because of a battery. It’s an issue for cars, too, but it’s much easier to find space and figure out structural rigidity and safety in a car framework than it is with bikes.

And then there is the fact that top-end bikes don’t just address their riders’ needs, but rather their desires and aspirations. And part of the joy of a ride out in the open – as opposed to a car where one is cushioned as in a protective shell – part of this pleasure is the sound of the engine, and even its smell. It’s a very special sensation, and I don’t think that many who enjoy it would be prepared to replace it. The weight of batteries also means it’s very hard to plan for any electric transition in large and long-distance airplanes and ships.

The situation now isn’t too different from 120 years ago, when for a decade or so it wasn’t clear if mass-produced cars would be powered by petrol or electricity. Eventually petrol won because it was easier to adopt – and at the time nobody could anticipate a century of oil supply shocks. Moreover, because petrol was so new then a new, unified standard could be set both technically as well as for a fuel distribution network. Electricity. on the other hand, was already present with one foot on the ground, but it was very localised, and the voltage in one region’s circuit was often different from that in others.

This voltage issue was obviously solved in the following decades, but although electricity seems invincible nowadays it’s not absolutely assured that it will remain so. Batteries’ mass has not been solved yet, and as demands for prolonged range and comfort increase some other technology may eventually offer a more efficient solution. We’ll have to wait and see.

And at some point we’ll also need to put the overall carbon footprint of an electric car on the table. It’s hard to get clear data, but the emissions from driving are not the only ones, and various estimates suggest that it is only well after 100,000 kilometres that an electric car’s carbon footprint equals that of a petrol car.

I’d say the only thing that’s certain is that we’re in a transition period, and that it’ll take quite some time.

It would probably make sense to consider our needs and desires, like you’ve said: most people need a small car for 11 months of the year, and then have several options what to do about it in the remaining one.

There’s no question that in considering our needs and desires in order to lead more sustainable lives, we’ll need to adopt some new habits and ditch some old ones. Each of us needs to reconsider our own needs, as technology can only address a certain part of this equation. Probably some things that we used to take for granted will need to be limited somehow, and it would be best, if the system – that is the political framework – could be designed so that each of us could choose what we are willing to give up and what not. For the time being this does not seem to be the case, and I believe that there is still a lot of work to be done along these lines, too.

Written by:

Boštjan Tadel

All photos/visualisations:

Studio Miklavc

GEM product photos:

Aleš Rosa

Bimota trade fair space photo:

Taka Asakawa

Bimota motorcycle concept visualisation:

Andrej Šenk / Studio Miklavc